Mark Wiese, Flight Projects Office Chief for NASA’s Launch Services Program, discusses the critical partnership between NASA civil servants and contractors as well as his role in driving cultural transformation at NASA.

Video Credit: NASA

As Kennedy Space Center (KSC) emerges as the nexus for federal and commercial space launches, Mark Wiese is helping teams bridge cultural gaps to ensure mission success for all.

Wiese, chief of the Flight Project Office in NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP), helps agency projects obtain launches while supporting the development of new commercial launch opportunities, such as the recent Venture Class Launch Services contract. APPEL News recently spoke with him to learn more about what he is doing to help all of the different cultures—from NASA science missions to commercial launch providers to those involved with major agency programs—find efficient ways of working together so that a wide range of projects can safely reach orbit.

APPEL News: Thanks for talking with us. As chief of the Flight Project Office, your focus is on launch services. Has that always been your area of expertise?

Mark Wiese: I began working with NASA as a contractor at Johnson [Space Center] in 2000, supporting the International Space Station Program. When I came to Kennedy in 2002, I worked in LSP as a quality engineer. My job was to review the as-built configuration of launch vehicles that put NASA science missions on orbit. I compared what the engineers planned to build with what was actually produced. Typically, there are configuration changes along the way because an anomaly comes up, and I looked at those changes. Eventually, I became the area manager for the safety and quality role of the support contract I worked on, supervising folks across the country. After Columbia, I jumped the fence and became a civil servant. I worked in LSP, then had the opportunity to move over to the Space Shuttle Program, and now I’m back in launch services again.

APPEL News: How did things change when you went from the contractor side to being a civil servant?

Wiese: One thing I embraced as a civil servant was the chance to put in place processes that could fix some of the things that had caused me angst as a contractor. For instance: how we write requirements for contracts. Typically, when we at NASA put out a contract for a support services workforce, we spend hours and hours writing those requirements, trying to document exactly what we want our support contractor to do. But in the aerospace environment, requirements are very dynamic. The environment around us changes based on what’s going on with our spacecraft or what’s going on with our launch vehicles. So no matter how perfectly you write a contract, it becomes challenging at times to perform and execute based on the specifics that are on paper. It can be tempting to keep focusing on the small things, trying to get it just right. But one thing that stood out to me—and this was when I was a contractor—was hearing a NASA director tell his people not to focus on the bean counting. Instead, he wanted them to provide good insight into how to buy down the risk for the mission. And that stayed with me: that we need to step back and think about how it all fits into the bigger picture. After that, as a contractor, I tried to chip away and change that culture so we’d focus on the overall mission. Later, when I joined the NASA side, I worked with the exact same group. I essentially just changed badges. So it opened up a lot of doors for me to really influence bringing value and changing the culture so the team looked at that bigger picture.

APPEL News: Facilitating a significant shift in culture sounds challenging. It is something you enjoy doing?

Wiese: I don’t know if it’s in my DNA, but I’ve always enjoyed process improvement and increasing clarity. Trying to take away any uncertainty people have about the goal they’re working toward. It’s usually all about good communication: making sure everybody understands what their role is, how they fit into the team, and that they’re all marching toward a common end goal. I gravitate toward situations where I can try to prove that we can do things differently: we can change our mindset and do something new. I try to help set up the culture so that people can work together and be successful. The satisfaction that comes out of doing that is enormous.

I had a chance to do it again when I joined the shuttle program in a management role. That was toward the end of the program, and I was pushed by my leadership to try to change the culture to prep us for whatever would come after shuttle. At the time, it was the Constellation Program. That was a big shift. Shuttle was structured around a government-designed launch vehicle, with government oversight and approval of every little step along the way. But the plan for the Constellation Program—and, now, the Commercial Crew Program and other commercially geared programs within NASA—was to introduce something different. We wanted a more risk-based insight model where NASA could be a little more hands off and efficient by leveraging commercial best practices and taking away the need for so much government approval at each step of a project. Essentially, we wanted to find a balance between a commercial-run operation and a government-run operation. So that was my focus: helping change the culture from the existing shuttle dynamic to a new model. My workforce was really set in the way we had been doing things for shuttle, so I tried to help them see that we could do things differently and be just as successful.

APPEL News: Is this the kind of work you do today in the Flight Project Office?

Wiese: I took on my current role maybe four months ago, so I’m still trying to stay in learning mode. I don’t want to stress out the people that work for me by throwing a change at them right away. I’m trying to listen and understand where we have opportunities to improve how we deal with our customers and how we deal with our teammates internally, ultimately focusing on making sure we get our job done and enable mission success for the agency.

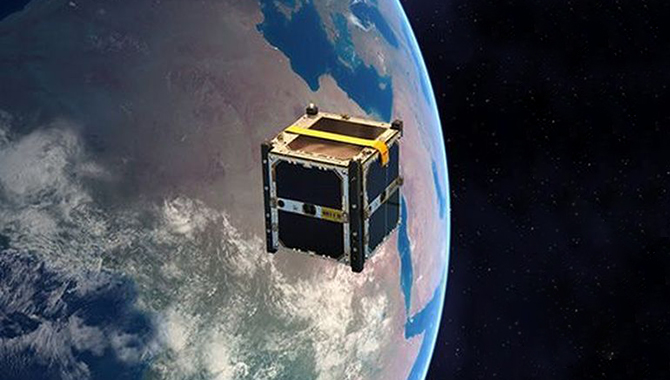

In terms of projects, I just finished working on the Venture Class Launch Services (VCLS) contract. Technically, it was geared toward helping CubeSats get on orbit. But really it was about opening the door for smaller spacecraft, not just CubeSats, to have a cheaper option to get to space. I spent the last three years working toward that.

APPEL News: Does the VCLS initiative represent a change in how NASA does business?

Wiese: It does. All three of the companies who received contracts are geared toward serving the commercial space industry. They have private investment money backing them. So, although NASA will use their services, it’s the first time a launch vehicle is being developed for a non-government customer. The issue is that government and private industry approach things very differently. At NASA, our focus is to buy down the risk to our spacecraft and protect the investment of the American taxpayers. On the commercial side, those rules don’t apply. You do what’s best for your shareholders and what proves the business case of your commercial company. So those are drastically different ways of operating.

APPEL News: How are you helping those two very different cultures work together?

Wiese: We’re mentoring the three VCLS providers to find a balance between the commercial approach and the government approach. They’re going to do what they need to do on the commercial side. But when it comes to working with NASA, we’re trying to help them understand that the way we do business is a little bit different than what they’re used to. We want them to understand how we work, and establish a good working relationship with them, so that when the time comes for them to fly a spacecraft that’s an order of magnitude more expensive and has a government payload, they already know how to contract with the government and they understand we’re not trying to be a hindrance. We’re not trying to change their business model, but we do need to protect the interests of the American people and NASA’s budget, and that affects how we do business. At the same time, we want to leverage commercial best practices, as I said before. So when we wrote the VCLS contracts, we tried to keep government requirements to a minimum. The good thing is we can tolerate a lot of risk because we’re flying CubeSats. The investment isn’t the same as for a spacecraft that’s taken six years and millions of dollars to develop.

APPEL News: VCLS is clearly a unique initiative. How did you get involved in helping develop a service that serves both the private and public space communities?

Wiese: LSP has launched traditional Earth observation and planetary science payloads for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. Over the years, we’ve had customers come to us and ask for ways to get a cheaper launch service. The lowest cost we had was maybe $50 million, with the majority of them being upwards of $100 million. So we started studying different approaches—but when it came time to actually try a new approach, none of our customers had enough money to do that. Then, in 2013, we were able to pull together a small amount of money—some strategic funds that our program had—to try to buy a launch service a little differently. The problem was, we didn’t have a payload for the launch. We looked around and saw that NASA’s [Educational Launch of Nanosatellites] ELaNa Program had a lot of CubeSats waiting to get rides on primary missions. We thought, “Why don’t we try to fly some of those? They can tolerate the risk, and we’ll be spending our strategic money in a good place because if it works, we’ll be giving them a ride; and if it doesn’t work, we haven’t hurt a spacecraft that’s been in design development for five or ten years.” So we started with that. Now, on the VCLS missions, we’re working the manifest to get a dozen or more CubeSats to fly on each of the VCLS launches. That’s exciting for the ELaNa Program, because they’ll be able to get more access to space. And some of the riskier CubeSats—ones with a propulsion system or something that would make a larger mission worry about giving them a ride as an auxiliary payload—can go up on a dedicated CubeSat flight, which can tolerate more risk.

APPEL News: What about NASA science missions that involve larger spacecraft? Will they use VCLS?

Wiese: Definitely. They helped us get VCLS moving. We started with a launch contract called NEXT: NASA Launch Services Enabling eXploration and Technology. In the end, that didn’t work but we learned a lot. It opened doors for us to get to VCLS. On VCLS, the Science Mission Directorate, specifically the Earth Science Division, was our biggest supporter. They saw us put that NEXT contract out and started to see the vision of what smaller launch vehicles could do from an Earth observation standpoint. They gave us a good injection of strategic investment money to allow us to go out and award the VCLS contract and, more specifically, get multiple awards so that we could really try to drive competition among these emerging providers.

APPEL News: Is the FAA involved in these commercial-provider launches?

Wiese: We wrote the requirements for all of the VCLS contracts to be FAA-licensed launches. The idea was to set up these commercial companies to meet their own commercially viable business models. That requires them to get an FAA-licensed launch because the majority of the payloads won’t be government sponsored. So we put in the contract requirements that, for NASA missions, we’ll buy an FAA-licensed launch. That way, we won’t change the way they do business. We’re starting to work with the FAA to make sure we can be complementary in the different analyses that we do. FAA is very focused on being a regulatory agency, where they set out the rules and make sure those rules are followed by the commercial providers. NASA, on the other hand, is more insight-based and focused on buying down the risk for our spacecraft. So we’re trying to find that healthy balance between the two so we can work together.

After launch, there’s another question. Once we have a bunch of these commercial satellites on orbit—who manages that traffic flow? Is that NASA? Is that Department of Defense? Or does the FAA go beyond just getting access to space to manage all these satellites in space? Till now, it’s been NASA and Department of Defense working together because we have been the owners of the majority of the spacecraft. But now you may start to see the scale tip a little bit the other way. We’re all trying to figure out whether the FAA has a role after launch.

APPEL News: What else is Launch Services involved in these days? Do you work with big spacecraft or launch vehicles like the Space Launch System (SLS)?

Wiese: Part of our mission is to use commercial assets to help get NASA satellites to space. But we are working with some spacecraft in the early design phase that now have to decide whether they want to fly on a commercially available solution or take the chance that the government “super rocket” will be ready when they need it. The SLS offers the advantage of speed. For a planetary mission, it might take five or six years to get to a destination if they use a commercial solution but only two or three years if they use SLS. So right now we’re in an early phase of talking with our customers about SLS. It’s not our rocket, but we can try to help. We can help our customers design an interface that would fit the rockets that we support, or we can provide a little bit of information about SLS. And we can try to help the SLS community, which isn’t used to dealing with these requests. We’re trying to fit in where we can without stepping on the toes of the SLS Program.

APPEL News: So you’re acting as a bridge, helping one internal customer work with another group at the center?

Wiese: Yes, and it kind of comes back to culture, too. Right now, our customers are used to the LSP processes, and they’re unsure about how they’d fit into the SLS process. So they want us involved if possible. [As a result,] we’re trying to help be that bridge—without trying to change the business model of SLS. We’re definitely not trying to take over that model! But if we can help merge thought processes and procedures for integration of spacecraft, all with the goal of making it easier for everyone, then we’ll do that.

APPEL News: It sounds like you really enjoy your work. What do you like most about it?

Wiese: I really enjoy trying to do things differently. I definitely love trying to prove we can do something that others think is impossible. This whole push for the commercial space industry is very exciting to see. For a long time, we believed NASA was the only organization that could do this on U.S. soil. But now the commercial industry is starting to get good roots and prove that they can be just as successful. So that whole cultural mesh between the government way of doing business and the commercial way of doing business is definitely something that excites me.

APPEL News: What have you found most surprising about your work?

Wiese: Probably the biggest surprise is that cultural change is not intrinsically hard. It’s people’s emotions about change that make it challenging. Everyone is well intentioned. Everyone is trying to do the right thing. But sometimes we end up at odds with each other because we’re not speaking the same language. Like I said before, it’s about good communication. We need to understand that we do have similar goals and we can find a way to work together. Engineers are very complex, smart people. Very detailed oriented. For cultural change to be successful, we have to help them step back and connect on a personal level. We want to help them realize we can all get to the same goal if we loosen our grip on the details, just for a little while, so we can all see the bigger picture. Then everyone can go back to focusing on their area of expertise. It takes a little bit of time to develop those relationships and make sure we can get past any barriers.

APPEL News: One last question. Do you have any advice for early-career engineers who want to become project managers?

Wiese: My biggest piece of advice for that newer generation that wants to get into program or project management is to think about ways that you can add value. Not just from your area of expertise, but from the other perspectives of program management: cost, schedule, technical. Think about that whole picture. Don’t lose sight of what you’re good at and what you’re focused on, just try to make sure you’re aware of how you can bring value to the solution across those other perspectives as well.

APPEL News: Thanks for talking with us about the work you’re doing to ensure NASA’s missions reach space.