Artist’s concept of the Block I version of the Space Launch System lifting off from Kennedy Space Center.

Image Credit: NASA

After examining the feasibility of including crew on Exploration Mission 1 (EM-1), NASA will move forward with the original plan to test Orion and SLS capabilities without astronauts.

EM-1 is the second installment in a three-part mission series designed to test NASA’s new Exploration Class human spaceflight capability, which includes the Orion capsule and the Space Launch System (SLS). The first mission in the series, Exploration Flight Test 1 (EFT-1), took place in December 2014. A Delta IV Heavy rocket sent the uncrewed Orion capsule 3,600 miles from Earth, where it became the first spacecraft to go beyond low Earth orbit (LEO) in more than 40 years. EM-1, also designed as an uncrewed mission, represents the first integrated flight of Orion and the SLS. The third mission in the series, EM-2, was expected to be the first to unite crew with Orion and the SLS.

This sequence was called into question in early 2017, when the White House approached the agency about reconsidering the design of EM-1 to include astronauts as a means of accelerating the development of NASA’s manned deep space exploration program. Acting NASA Administrator Robert Lightfoot and William Gerstenmaier, Associate Administrator for the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate (HEOMD), put together a team tasked with assessing whether this could be done. They focused on determining what would need to change on the EM-1 spacecraft system to safely include crew, what new tests would have to be conducted, what additional risk would be incurred, and how all of that would impact the schedule and budget for the mission.

“At the end of the day, we found that technically it would be feasible to fly crew on EM-1 as long as we had a commitment of additional resources and schedule, and recognizing that the technical risks that we identified still were going to need mitigation plans as we moved forward,” said Lightfoot. Mitigation efforts would include modifications to the existing EM-1 heat shield, inclusion of a life-support system, performing accident abort tests, and developing software to support crew use.

Despite that positive assessment, NASA and the White House agreed that pursuing the original plan to fly EM-1 without crew was most consistent with available resources and long-term plans. “It gets us back to flight sooner as a team,” said Lightfoot. “[A]n uncrewed mission will actually help EM-2 be a safer mission when we put crew on there. So we’re going to continue with our baseline plan.” He added, “[We] firmly believe that will make the right steps for us to push humans deeper into space.”

With the decision to preserve EM-1 as an unmanned flight, the agency will follow the original mission profile. Launching from Kennedy Space Center (KSC), the SLS will propel Orion 275,000 miles from Earth into a distant retrograde orbit. Over the course of the three-week mission, Orion will fly around the moon and then farther into space where it will collect data as mission control assesses the performance of the spacecraft and its systems. Eventually, the capsule will reenter Earth’s atmosphere and splash down in the ocean near San Diego.

“We want to push the vehicle really hard from a technical standpoint,” said Gerstenmaier. “When we put crew on, we would not do this same flight test sequence. We would stay close to the earth for several orbits before we go around the moon, and that’s to check out systems. We would be poised, if something goes wrong, to get the crew back immediately. But since we don’t have crew on this vehicle, we will push as hard as we can the Orion systems, the navigation systems, the propulsion systems.” The flight will end with a skip-cycle: Orion will reenter Earth’s atmosphere, leave it again for a moment, and then come back in to land off the coast of California. Findings from the flight will be used to inform Orion and SLS development for EM-2.

EM-1 was originally slated for 2018, but the agency decided to push back the flight until 2019, with an exact date to be selected in the next few months. This decision was based on a number of factors, including delays in European service module deliveries, damage to the Michoud assembly facility from a tornado in February, and an accident with the qualification oxygen tank, which rendered it unrepairable.

Another reason for the new launch date is the complexity of the program and the novel work involved. “We picked systems like the modern manufacturing down at Michoud to lower our production ops costs,” said Gerstenmaier. “[W]e’re pushing a lot of brand new manufacturing, and I think that new manufacturing has caused some of the delays we’ve seen. No one welds material in the way that we’re welding material at the thicknesses we’re welding for this tank. So we’re actually paving the way [in terms of] manufacturing development process.”

Lightfoot and Gerstenmaier emphasized that time spent on EM-1 will benefit the agency, the nation, and the world over the long term, as it is a crucial stepping stone on the path toward developing an entirely new capability.

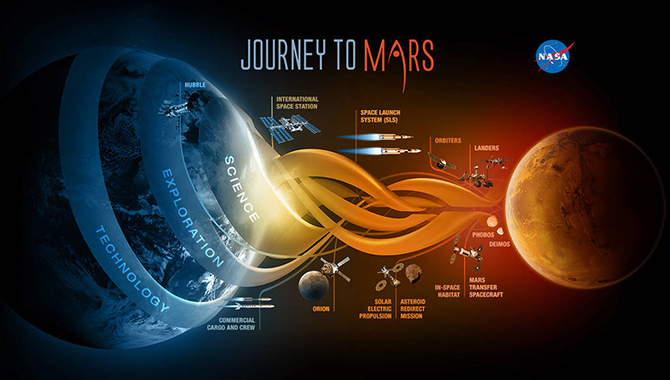

“We’re really building a system,” said Gerstenmaier. “We are using the unique capabilities of [the SLS] and the Orion capsule to put a piece of infrastructure in space around the moon—we call it the deep space gateway—that can be used to do command robotic activities on the surface of the moon. It can [also] be a staging point for later Mars missions.” The plan is to allow private industry and international partners to use NASA’s infrastructure to achieve their space-based objectives as well.

“We’re essentially building a multi-decadal infrastructure that allows us to move human presence into the solar system,” he said.