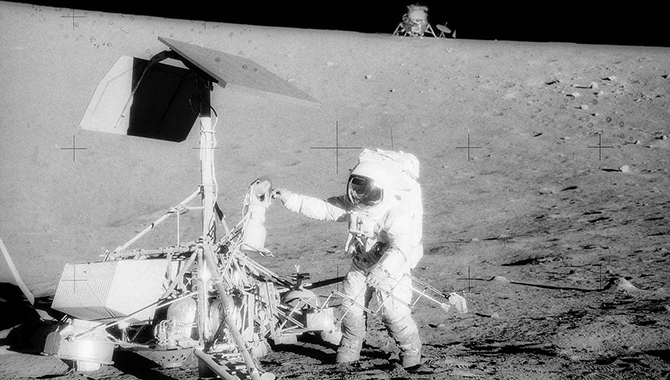

Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad Jr. examines the TV camera of Surveyor 3 prior to detaching it and returning it, and other pieces of the lander, to Earth for analysis.

Credit: NASA

Team solves glitches to save NASA’s second mission to land on the Moon.

On November 14, 1969, the sky was gray, and it was raining at what is now Kennedy Space Center. The crew of Apollo 12—Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad Jr., Lunar Module Pilot Alan L. Bean and Command Module Pilot Richard F. Gordon Jr.—spent the morning concerned that the launch would be scrubbed, a move that would have pushed the launch into December.

With weather concerns overruled and President Richard M. Nixon in attendance, standing beneath an umbrella, Apollo 12 blasted off at 11:22 a.m. Conrad had just commented on the “lovely lift-off” when a lightning strike, 36 seconds after launch, tripped circuits that controlled crucial functions in the command and service modules. Another, smaller strike occurred at 52 seconds. The crew joked later that so many warning lights came on at once that it was too bright to see.

“Okay, we just lost the platform, gang. I don’t know what happened here; we had everything in the world drop out,” Conrad said to mission control. “…We had some really big glitch, gang.” Warning lights indicated issues with the service module’s fuel cells, fuel cell disconnects, and the AC systems that power the spacecraft’s controls. The Saturn V’s control system, unaffected, continued launching Apollo 12 on a perfect course.

“We never anticipated anything like that,” recalled Gordon, in an oral history. “It was not part of the training syllabus! Simulations didn’t even come close to it.” As the command module pilot, Gordon recalled being competitive with the crew and mission control, racing to be the first to find answers during training.

“When those lights came on, I kind of looked up at the lights, I looked over at Al [Bean], and I looked back again, and I said, ‘Okay, Al. It’s all yours!’ And whether that’s true or not, I always tell it that way because that’s the way I felt! Because I didn’t know what the hell to do,” Gordon said.

Bean recalled being confused by the situation, as well. “So, I’m there dividing my time between thinking, ‘What is going wrong that would give us this indication?’ and, ‘Here’s my chance, and I don’t have the slightest idea what to do.’ ” He fell back to a rule he’d learned as a test pilot — “If you’re going the right direction, don’t do too much.”

Bean took time to think about this situation before him and then cautiously reset the fuel cells one at a time, cognizant that he might be putting power into a short circuit. He monitored the amps and volts to see how the spacecraft reacted to each of the three switches he reset. “Each time I was waiting for something to go “Beep!” you know, and everything go off again. It never did. Suddenly we got that. Then I reset the AC buses and all that other,” Bean recalled in an oral history.

“…That’s only a myth: test pilots make snap judgments. Not the ones still around,” Bean said.

With the key systems back online, the crew was set to go to the Moon, unaware that there was a debate on the ground about the possibilities of unseen damage to the spacecraft, especially to the system that deployed the parachutes. If that system failed, the capsule would crash into the ocean. After weighing the options, the decision was made to go the Moon.

Gordon remembered the flight to the Moon as “…three days of not doing a great deal, but the mission is all still in front of you. …it’s full of anticipation. The Earth’s getting smaller, and the Moon’s getting bigger. And there’s not a lot of activities to do. You’re checking out the spacecraft and the guys had a chance to get in the lunar module and check it all out before we got there.”

The Apollo 12 mission was ambitious, with a pinpoint landing on the Ocean of Storms, near the site of Surveyor 3, an uncrewed mission that landed on April 20, 1967 and analyzed the soil for its weight bearing capacity, radar reflectivity and thermal properties—all crucial to the success of Apollo 11.

Conrad, who was five inches shorter than Neil Armstrong, made a joke about that height difference as his first words on the Moon, ending the rumor that NASA was scripting what the astronauts said. “Whoopee! Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me,” Conrad said, before noting that he could clearly see Surveyor 3. “The old Surveyor, yes sir, ha, ha, ha… Does that look neat? It can’t be any further than 600 feet from here. How about that?”

On their first extravehicular activity (EVA), Conrad and Bean deployed a suite of experiments known as the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), took photographs, and collected soil and core samples. During the second EVA, the astronauts collected 70 pounds of soil and rocks and hiked to Surveyor 3, retrieving several parts to return to Earth for analysis.

Meanwhile, Gordon became the second of only six humans to orbit the Moon alone in a spacecraft. He recalled the experience as “Wonderful. Never—never bothered me a bit. As a matter of fact, probably never even thought about being out of communications with anybody on Earth. Because when the Sun shines on the Moon, which it does half of it all the time, there are features that you can look at and see that you hadn’t seen before.”

Once Conrad and Bean rendezvoused with the Command Module and rejoined Gordon, the ascent stage of the Lunar Module was jettisoned to impact the surface of the Moon near the ALSEP seismometer the astronauts had deployed. The impact reverberated for an hour and a half.

Apollo 12 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on November 24, 1969 at 3:58 p.m., about three miles off target, but within sight of the recovery ship, the USS Hornet. Three days later, the astronauts celebrated Thanksgiving inside NASA’s Mobile Quarantine Facility, a heavily modified Airstream trailer.