The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) seen from the Space Shuttle Discovery.

Credit: NASA

Scott “Scooter” Altman discusses five key takeaways from complex missions.

The Hubble Space Telescope has dramatically changed scientific understanding of the Universe. Released into orbit by the Space Shuttle Discovery in April 1990, Hubble was the first telescope designed to be serviceable by astronauts in space. This became important sooner than expected, when NASA discovered that the edge of the telescope’s primary mirror was too flat by about 1⁄11,000 of an inch. That miniscule difference meant the images Hubble was sending back to Earth were blurred.

Scott “Scooter” Altman was a test pilot in the U.S. Navy in 1990, but was interested in becoming an astronaut following an official visit to Johnson Space Center where he realized that many of the astronauts there had followed a similar career path to the one he was on. He remembers following news of the launch of Hubble and efforts to repair the initial problem with the telescope. When he was selected to be an astronaut in 1994, he had no way of knowing that years later he would become instrumental in extending the life of the Hubble Space Telescope, commanding two Space Shuttle missions to service it.

Altman was a guest recently on APPEL Knowledge Services’ Virtual Project Management Challenge, sharing lessons learned from the Hubble Servicing Missions. Altman was the Commander of STS-109 and STS-125, the final two servicing missions. The missions were ambitious. STS-109 included five EVAs, totaling more than 35 hours in space. The crew installed the Advanced Camera for Surveys, new solar arrays, a new power control unit, and the Multi-Object Spectrometer. STS-125 also included five EVAs, totaling more than 35 hours. The crew repaired two key instruments, and extended Hubble’s life with new batteries, gyroscopes, and a new computer.

“There were times every day I thought I was going to be the commander of the crew that killed the Hubble space telescope,” Altman recalled of STS-125. “But when we got to that point we’d finished everything that we could possibly do … I was just incredibly proud of the whole team, both the folks I had with me on orbit and the folks on the ground who made it all possible. So, it was a team effort all the way.”

Altman said that as he reflects on the two Hubble missions for Lessons Learned, he finds the same five success principles that guided him throughout his career: commitment to a common goal, teamwork and support, communication, preparation, and imagination.

“We talked about the role of the mission commander to be kind of the leader and motivator, but also coordinator of things,” Altman said. “And I had basically five principles that I wanted us to use on the flight. …They’re pretty straightforward and I think they apply to almost any project you have here on the ground or in space.”

Altman continuously promoted a vision for success on the complex Hubble Servicing Missions, while creating a cohesive group in which talented individuals had the leeway to do their jobs. Altman said that in his experience communication is the principle that can become the most problematic.

“Most of the times when I look at a problem that developed, there was a breakdown in communication somewhere along the way, where people who are trying to do their best are always working for that, but sometimes they’re going in different directions because they didn’t hear what somebody else said, and the communication broke down,” Altman said, noting that the process involves sharing, listening, and seeking out dissenting opinions.

“There’s what’s broadcast and then there’s what’s interpreted, and you’ve got to make those things match for communication to actually take place,” Altman said.

The complex Hubble Servicing Missions required the astronauts to train for three years, practicing the tasks they would accomplish in space in two weeks, divided over five EVAs. By the time they had completed that training, it almost felt to them that they’d already successfully completed their goals in space. Even with all that preparation, however, the crews ran into unexpected situations nearly every day.

This is where the fifth principle of imagination comes into play, Altman said. First, the crew imagined the things that could go wrong with the mission and then they prepared for them. But it’s difficult for an astronaut on Earth to imagine everything that could go wrong in space. So, imagination also helps them solve the unexpected situations in real time.

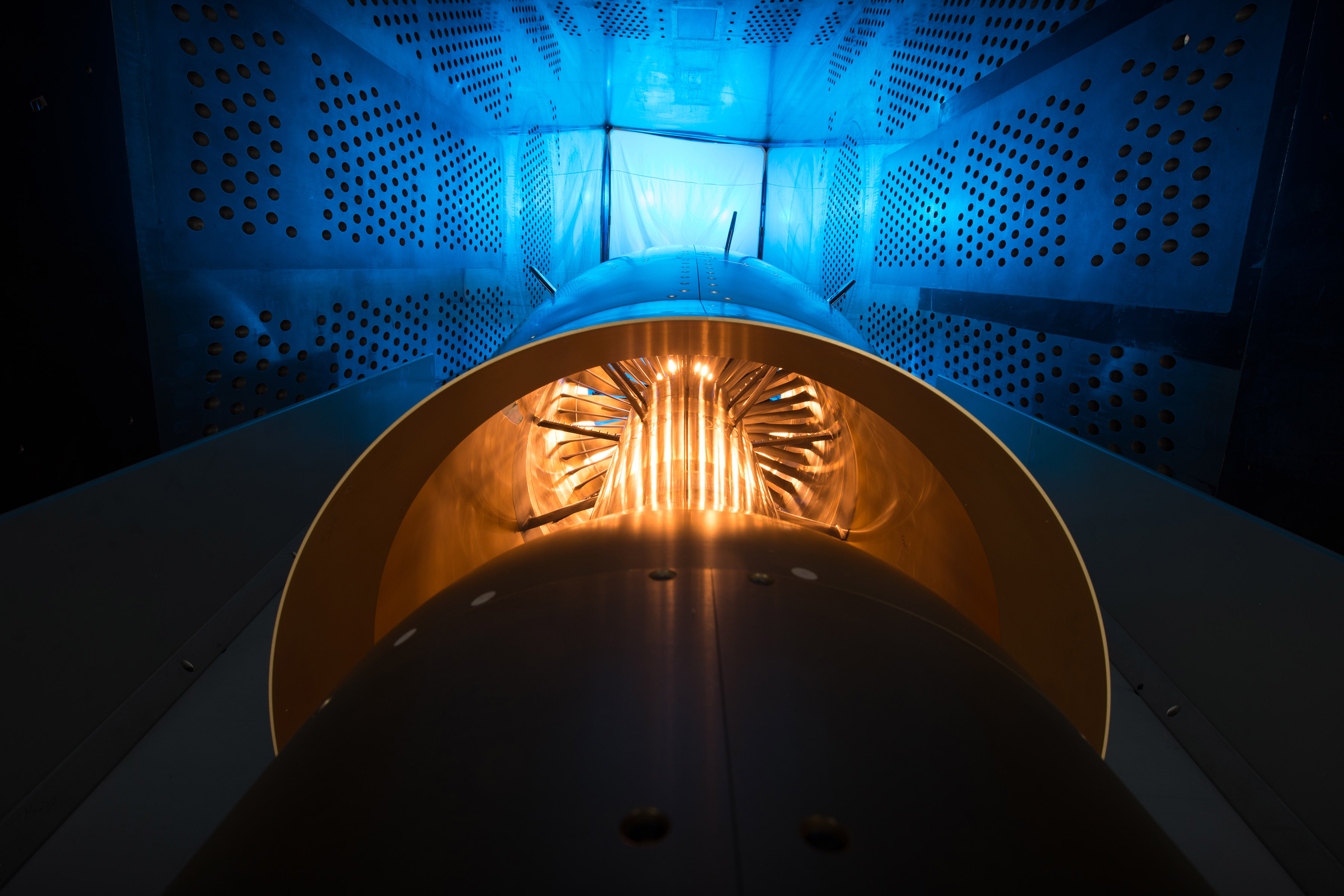

For instance, when the crew of STS-125 began removing the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 from Hubble to install Wide Field Camera 3, a bolt that should have been loosened with a torque wrench set at 42 ft lb still couldn’t be removed when the wrench was put on its maximum setting of 48 ft lb. Out of contingency procedures, the crew and the team on the ground began weighing the option of using a simple breaker bar, with no torque limit.

“So, there’s imagination of what can I do with the tools that I have available to me in flight to try and achieve that goal?” Altman said. The improvisation worked and the Wide Field Camera 3, a key instrument, was installed.

On the VPMC, which is available for on demand viewing here, Altman recalled how he wanted to be a pilot from the age of three and that although he heard “no” many times during his career, his parents encouraged him, saying “You can do anything you want, as long as you work hard, do your best and never give up.”

“And I think it’s what you do after the ‘no,’ or after the failure, that really shows what you’re all about and your commitment to that goal,” Altman said.