The Space Shuttle Columbia launches before dawn on January 12, 1986 with a tight-knit crew that deployed a key communications satellite.

Credit: NASA

Tight-knit crew deploys a key communications satellite and performs science missions.

On January 12, 1986, 35 years ago this month, the Space Shuttle Columbia sat on Launch Pad 39A, once again awaiting launch. Robert L. “Hoot” Gibson sat in the Commander’s seat for the first time, having piloted STS-41-B two years earlier. At Gibson’s right was Pilot Charles F. Bolden, Jr., an accomplished fighter pilot about to embark on his first spaceflight. Bolden recalled in an oral history that the crew was relaxed as the countdown progressed that morning because it was forecast that wind conditions would likely prevent the launch.

The crew had become familiar with launch delays over the past month, having been strapped into Columbia five times and come within seconds of launch twice. The original launch target of December 18 was pushed back to the 19th because of an issue closing out the orbiter aft compartment.

The countdown reached T -14 seconds on December 19, when what was later determined to be a false reading indicated that the right solid rocket booster’s hydraulic power unit was exceeding its RPM limit. With six days until Christmas and a lengthy repair ahead, the crew members were released from preflight quarantine to go home.

The next attempt, on January 6, reached T -31 seconds before an issue with accidental drainage of liquid oxygen from the external tank forced the launch to be scrubbed. Launch attempts on January 7, 9, and 10 were also scrubbed.

“So, we went out and we were about as loose as you could be that morning,” Bolden recalled of January 12. “And they went through the countdown, came out of the holds and nothing happened. ‘Ten, nine, eight, seven, six.’ And we looked at each other and went, ‘Holy—we’re really going to go. We’d better get ready.’ And … the vehicle started shaking and stuff, and we were gone.”

Even after months of training, and knowing that lift off is at nearly 3 Gs, the launch of a space shuttle was surprisingly loud, sudden, and forceful, Gibson recalled in an oral history. In the simulator, he recalled, the shuttle had moved past the launch tower briskly and when the Solid Rocket Boosters fired, they added a significant amount of noise and vibration to what the three main engines were already producing.

“No, that’s not what happens,” Gibson said. “What happens is okay, we light the three Main Engines. Those things are so noisy, you can’t hear yourself think. … So, when the Booster rockets light, you don’t hear an increase in noise, because it’s already as noisy as it can possibly be. What you do notice is you are slapped back in your seat, and that launch tower is gone. It feels like a catapult shot off the front of an aircraft carrier.”

Early in the launch, as the shuttle was shaking and vibrating, Bolden looked at the instrumentation and saw an indication of a helium leak in one of the main engines. “…Had it been true, it was going to be a bad day.” Bolden and Gibson worked through a series of procedures to isolate different portions of the system and determine the location of the leak.

“And then all of a sudden, I looked back down, and it looked like we were making helium, so I knew that couldn’t be true, because you don’t do that,” Bolden recalled. “So, I told Hoot. I said, ‘Hey, I think we’ve got a false indication here. I think we’ve got a sensor problem.’ And Hoot took a look. He said, ‘I think you’re right.’ ”

William “Bill” Nelson, then a U.S. Representative from Florida’s 11th district, served as a Payload Specialist on the mission, becoming the second member of Congress in space. He served alongside Mission Specialists Franklin R. Chang Díaz, Steven A. Hawley, George D. Nelson and Payload Specialist Robert J. Cenker. The crew was especially close, with some members sharing impromptu runs around Kennedy Space Center before the flight and playing in a band together.

On the first day in orbit the crew accomplished the mission’s primary objective, deploying Satcom K1, a third-generation communications satellite owned and operated by RCA Americom. Satcom K1 was part of a series of satellites that dramatically transformed long distance telecommunications, including how cable television content was transmitted.

The crew joked that they were an “end-of-year-clearance flight” because Columbia carried more than 20 smaller science missions focusing on everything from blood storage to protein crystal growth and materials science, Bolden recalled. “So, we had Congressman Nelson and every experiment known to man that they couldn’t get in [earlier flights].”

After launch, NASA reduced the flight from seven days to four, but STS-61-C was waved off multiple landing windows because of weather conditions at both Edwards Air Force Base and Kennedy Space Center, pushing the mission back to six days. Columbia, which had been originally scheduled to land in daylight, landed at Edwards Air Force Base before sunrise on January 18, 1986.

“…With a daytime scheduled landing, you would have thought that we wouldn’t have been ready for that,” Bolden recalled of landing in the dark. “Hoot, in his infinite wisdom, had decided that half of our landing training was going to be nighttime, because you needed to be prepared for anything. And so, we were as ready for a night landing as we could have been for anything.”

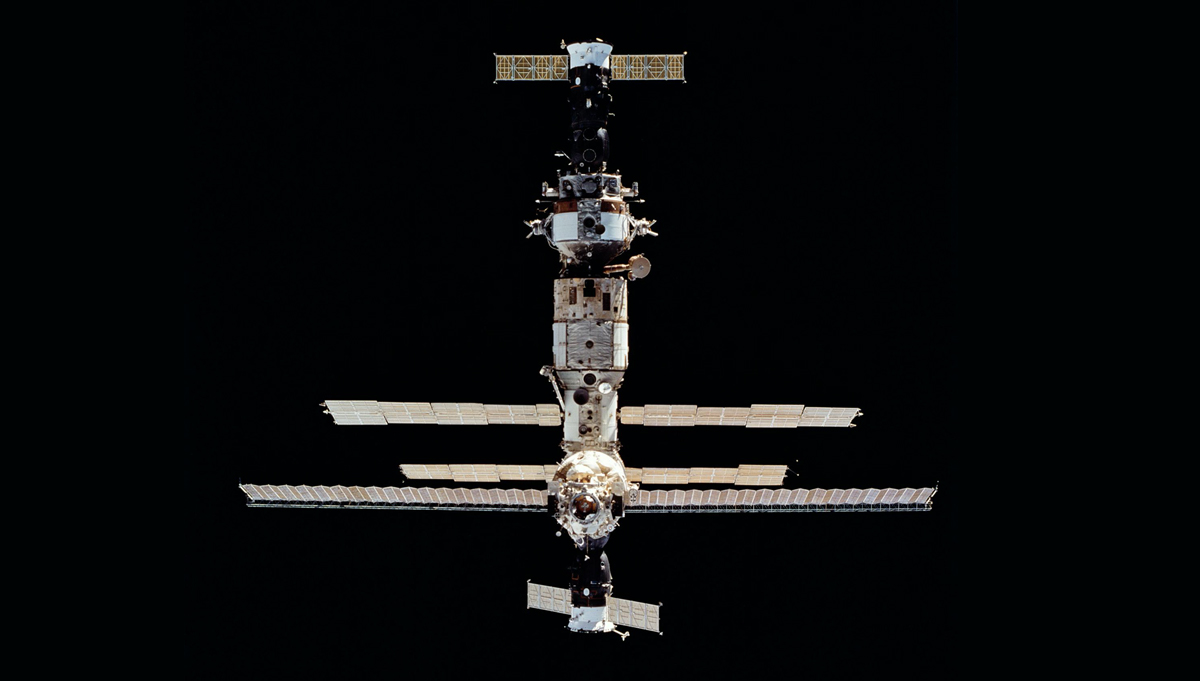

Gibson went on to serve as Commander for three more shuttle flights: STS-27, STS-47, and STS-71, the first shuttle mission to dock with Russian Space Station Mir. Bolden went on to pilot STS-31 and served as Commander of STS-45 and STS-60. In 2009, President Barack Obama appointed him as NASA Administrator, a position he held until January 20, 2017. Chang Díaz flew aboard the shuttle six more times, sharing the record for most spaceflights with NASA astronauts John W. Young and Jerry L. Ross. Nelson went on to represent Florida in the U.S. Senate, where he championed human space exploration, and serves on the NASA Advisory Council.

“We have been dear friends,” Gibson said of the crew in January 2016. “We’ve had at least three reunions now, and we’re going to have another one in March. We all dearly love each other. This has been by far the closest crew that I’ve ever been with, trained with, and kept up with over all these years.”

To learn more about STS-61-C and all 135 space shuttle missions, please visit APPEL Knowledge Services’ new Shuttle Era Resources page.