The Space Shuttle Program returned to flight on September 29, 1988—33 years ago this month—with the launch of Discovery on STS-26 from Launch Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center.

Credit: NASA

Team of spaceflight veterans begins recovery with STS-26.

In September of 1988, 33 years ago this month, the focus was on Launch Pad 39-B at Kennedy Space Center, where NASA was preparing the Space Shuttle Discovery for mission STS-26. Then-president Ronald Reagan had visited with the crew in the days leading up to launch, as had the top anchors of ABC, CBS, and NBC news. The mission would be a return to flight following 32 months of investigation, redesign, and modifications triggered by the Challenger tragedy.

“Do you think you’re ready?” the media asked Commander Frederick “Rick” H. Hauck. Hauck had free access to attend any senior management meetings he chose to attend relating to mission preparations and he was confident that “everything had been done that could be done” to prepare the Shuttle Program to return to space.

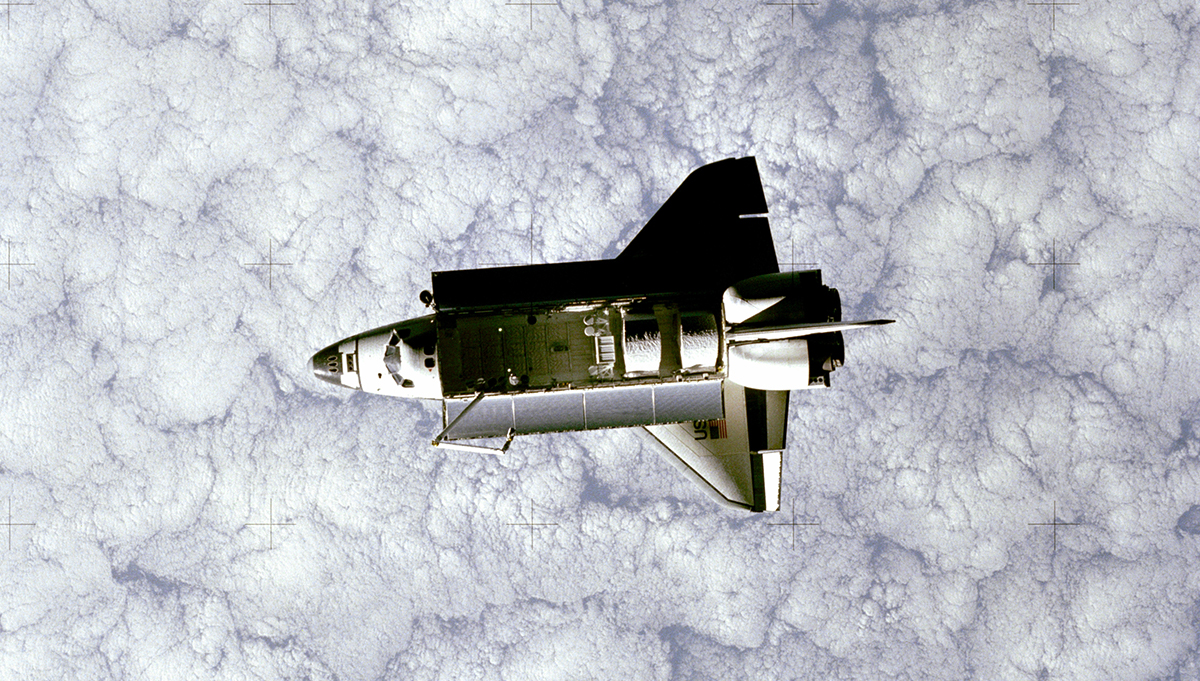

Discovery, fitted with redesigned solid rocket boosters, had been rolled out of the Vehicle Assembly Building on its mobile launch platform on July 4. Before that, it had spent 7 months and 22 days in the Orbiter Processing Facility, where technicians made more than 200 modifications and disassembled, checked, and reassembled many of the orbiter’s key systems. In the weeks ahead, it was tested extensively.

On the front row are Astronauts Frederick H. (Rick) Hauck (right), commander; and Richard O. Covey, pilot. On the back row are Astronauts John M. (Mike) Lounge, David C. Hilmers and George D. Nelson.

Credit: NASA

The morning of September 29, 1988 was sunny on the Florida coast, but with reports of unfavorable upper atmospheric wind conditions that would delay the launch. Hauck, Pilot Richard O. Covey and Mission Specialists John M. Lounge, David C. Hilmers, and George D. Nelson were all spaceflight veterans, the first time NASA had assembled such a crew since Apollo 11.

“It makes a big difference when you have all veterans. The first time you’re just overpowered by the sensations. The second time, the test pilot in you kicks in, and you start saying, ‘Okay. Oh yeah, that’s what I’m feeling there. That’s what that is. Okay, and this is going to happen. Yes, I’m ready for that,’” said Covey in an oral history.

The astronauts were wearing new, bright orange space suits. The Advanced Crew Escape Space Suit System was a full-pressure space suit with its own oxygen supply, liquid cooling, parachutes that would deploy automatically in high-altitude emergencies, and automatic-inflation life preservers. The suits were designed to create a survivable environment for the astronauts during launch or reentry emergencies at altitudes as high as 100,000 ft. And although Covey recalled the suits were uncomfortable, he managed to continue a personal tradition.

“I get on the launch pad, and I go to bed,” Covey recalled with a laugh. “I don’t think there’s been a flight I’ve been on that I didn’t go to sleep on the launch pad for some period of time. It may be five minutes, ten minutes, but you have to relax, and so, you know, in relaxing, I’ll go to sleep. I don’t miss anything critical. They talk to me, I wake up.”

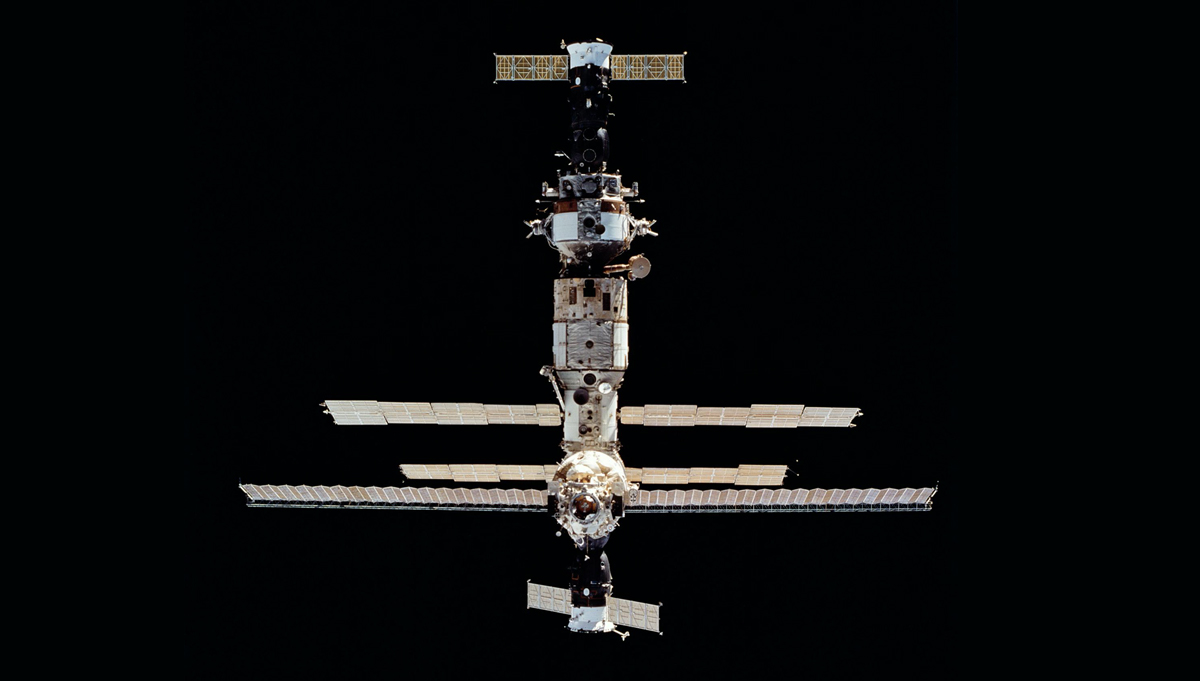

Following 1 hour and 38 minutes in delays, STS-26 launched at 11:37 a.m. The four-day mission was straightforward, with the primary goal of deploying the second of NASA’s Tracking and Data Relay Satellites, TDRS-3. This advanced communications satellite reached geosynchronous orbit via an Inertial Upper Stage, a 17 ft. long, 9 ft. diameter, two-stage, solid fuel rocket. The TDRS-3 (known as the TDRS-C before it reached orbit) became part of a growing system that relays to Earth data from other satellites, the International Space Station, and the Hubble Space Telescope.

Inertial upper stage (IUS) with tracking and data relay satellite C (TDRS-C) located in the payload bay (PLB) of Discovery, Orbiter Vehicle (OV) 103, is positioned into its proper deployment attitude (an angle of 50 degrees) by the airborne support equipment (ASE).

Credit: NASA

The crew conducted several science experiments in orbit. One tested the feasibility of using infrared light to transmit astronaut-to-astronaut communications within a spacecraft. Another was designed to determine how magnetic composite materials made in microgravity compare with those made on Earth. A third looked at how red blood cells clump together in microgravity to determine if Low-Earth Orbit could play a role in clinical research and medical testing. The astronauts also used the payload bay cameras to photograph lightning discharges at night below the shuttle. The observations led to improved sensors to detect lightning via satellite.

Near the end of the mission, the crew gathered to honor Commander Francis “Dick” Scobee, Pilot Michael J. Smith, Mission Specialists Ellison S. Onizuka, Judith A. Resnik, and Ronald E. McNair, and Payload Specialists Gregory B. Jarvis and S. Christa McAuliffe who died aboard Challenger. Each member of the STS-26 crew spoke during the brief ceremony.

“Today, up here where the blue sky turns to black, we can say at long last, to Dick, Mike, Judy, to Ron and El, and to Christa and to Greg: Dear friends, we have resumed the journey that we promised to continue for you; dear friends, your loss has meant that we could confidently begin anew; dear friends, your spirit and your dream are still alive in our hearts,” Hauck said, concluding the memorial.

Discovery returned to Earth on October 3, 1988, landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California, having traveled 1.7 million miles.

“After STS-26, we went back to NASA. We went to all of the space centers, and we went to the contractors who built the hardware. We went to Downey, California, where the Space Shuttle had been built. We went to Palmdale [California], where they’d been modified,” Hauck recalled, in an oral history. “The objective was to continue this healing process…”

To learn more about STS-26 and all 135 space shuttle missions, please visit APPEL Knowledge Services’ new Shuttle Era Resources page.