The satellite rescue attempt during STS-51-D included an unscheduled rendezvous maneuver, an unscheduled spacewalk, and a highly unusual request: Build a fly swatter.

Credit: NASA

Well-trained shuttle crew works to activate malfunctioning satellite.

On April 12, 1985, when they sat in the Space Shuttle Discovery beneath overcast skies at Kennedy Space Center, the crew of shuttle mission STS-51-D expected a delay. The launchpad abort of STS-41-D on June 26, 1984, had caused flight cancellations and payload reconfigurations that rippled into the spring of 1985 and changed how the crew of STS-51-D trained, what shuttle they took into space, and what was in the payload bay.

“We trained on three different payloads,” recalled Mission Specialist M. Rhea Seddon in an oral history.

The extra training, however, was about to pay off.

When the countdown resumed, 37 years ago this month, at T-minus-nine minutes, the crew prepared for launch. “…All of a sudden there’s this big scramble to tighten up your harnesses, get your helmets back where they’re supposed to be, and everybody’s going, ‘Oh, my gosh, we’re really gonna go,’ ” recalled Donald E. Williams, the mission Pilot, who was making his first spaceflight. He was to the right of Commander Karol J. Bobko, a veteran of STS-6.

“It was a quite a lot more than I expected, in looking back at that,” Williams recalled in an oral history. “It’s one of those things where you hope you’re pointed in the right direction, because it’s going somewhere for sure when the Solid Rocket Motors light. … It’s a very rough ride [with] a lot of mechanical vibration, a lot of heavy-duty low-frequency noise and a lot of things shaking and rattling…”

The crew of STS-51D: Front row, from left: Commander Karol J. Bobko Pilot Donald E. Williams and Mission Specialists M. Rhea Seddon and Jeffrey A. Hoffman. Second row, from left, Mission Specialist S. David Griggs and Payload Specialists Charles D. Walker and E. Jake Garn, then a sitting U.S. Senator.

Credit: NASA

U.S. Senator Jake Garn was seated at the far right on the middeck, the first sitting member of Congress to fly into space. Garn, an experienced pilot with more than 17,000 hours of flying time in military aircraft, had trained hard for the mission and earned the respect of the crew.

“Jake was a great person. He had more flying time than I did,” Bobko recalled in an oral history. “He knew what it was to be a crew member. You know, I’d call him up and I’d say, ‘Jake, we need you down here.’ And he’d say, ‘Yes, sir,’ and he’d be down the next day for the [simulation]. … He was a great mission specialist.”

The mission that changed three times on the ground changed again in space. On day two, the crew deployed the LEASAT 3, a 17,000 lb. communications satellite. They watched as LEASAT 3 left its cradle in Discovery’s payload bay and ejected smoothly into space. The satellite’s omni-directional communications antenna failed to deploy, however, and its perigee kick motor didn’t activate.

Discovery pulled a safe distance from LEASAT 3 and personnel on the ground began formulating a plan to rescue the satellite. This rescue attempt would include an unscheduled rendezvous maneuver, an unscheduled spacewalk, and a highly unusual request.

“…[Mission] Control Center came back, and they said, ‘We want you to build a fly swatter…,’” Williams recalled. These fly swatter-like devices, built by repurposing materials aboard the shuttle, were to be attached to the end of the remote manipulator system, creating a flexible extension on the arm that could then be used to try to flip the arming lever on the satellite’s side, in an attempt to activate it.

Although Bobko and Williams had trained for a rendezvous in an earlier iteration of the mission, the checklists for the procedure were not aboard Discovery. “They transmitted this entire checklist up, which ended up [being] a roll of teleprinter paper that was maybe fifty feet long and it was all over the middeck,” Williams recalled. The astronauts cut the unwieldy banner into pages and pasted them into a book to create a rendezvous manual.

“I mean, you’re bringing [together] these two spacecrafts that [are] doing 17,500 miles an hour… So, you know, it’s not a trivial task,” Bobko recalled.

“Rendezvous in space is a fairly complicated process,” Williams agreed. “…You have to take the orbital mechanics into effect, and there are several maneuvers and burns and things that have to be done at very precise times in order to keep from either overshooting it or crashing into it or missing the thing entirely.”

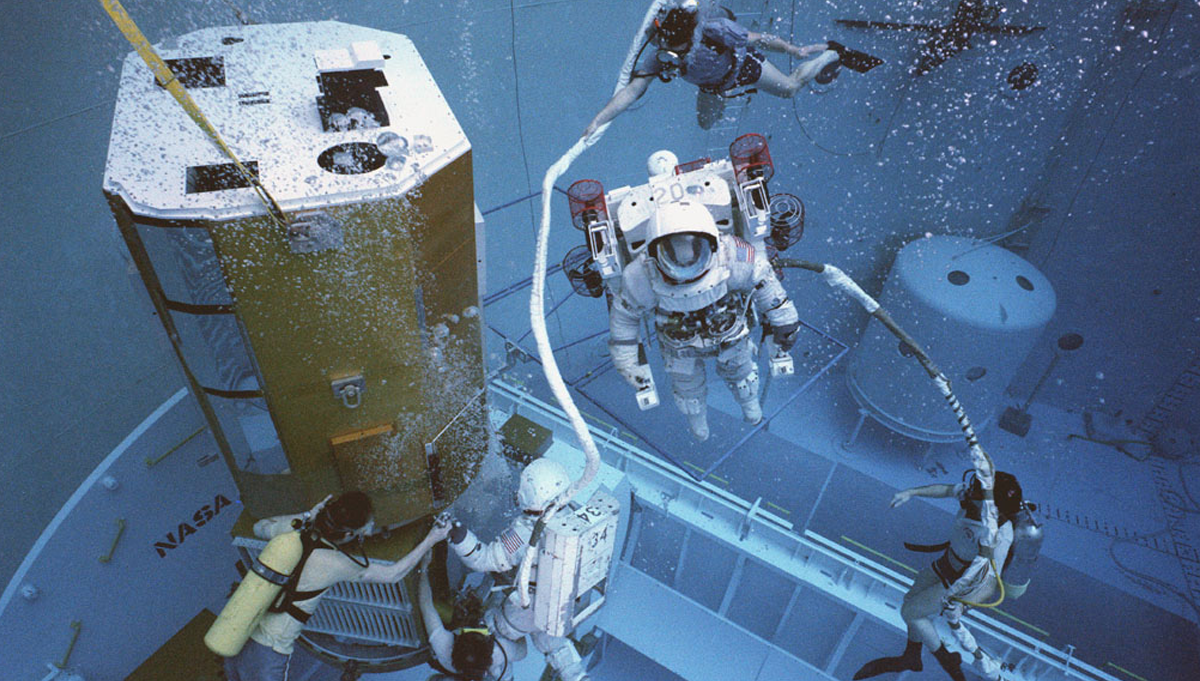

Meanwhile, Mission Specialists Jeffrey A. Hoffman and S. David Griggs prepared to make the first unscheduled extravehicular activity (EVA) of the shuttle era.

Hoffman, Seddon, and Griggs pose in front of the crew, holding the makeshift “fly swatters” that would be used in an attempt to activate the LEASAT 3 satellite.

Credit: NASA

“I was the first one out. … We had the fly swatters with us, and the little wrapping tool that we were going to use to hold them on. Dave and I figured out who was going to do what. Then the next thing I knew, [I opened] the hatch, and it was just when the Sun was setting. So, the whole shuttle was lit up red, and it was just so spectacular,” Hoffman recalled in an oral history.

“The problem was that since we weren’t planning an EVA, we didn’t have any foot restraints, we didn’t have any special tools, and so each of us had to use one hand to restrain ourselves. You could only work with one hand. We were trying to coordinate me using one hand, Dave using one hand. Your body is flapping all over the place, but we were pretty well-trained. We did it,” Hoffman recalled.

With the fly swatters attached, Seddon worked the shuttle’s remote manipulator arm. “We pulled on that switch, we tugged on it… We didn’t know whether that switch was almost to the on position, and a good tug on it would pull it or make the contact and start the sequence,” Seddon recalled.

Despite the valiant efforts by the crew of STS-51-D, LEASAT 3 did not activate. It would be repaired later that year by the crew of STS-51-I, who installed new components to bypass the hardware deemed the most likely cause of the issues.

STS-51-D landed at Kennedy Space Center on April 19, a two-day extension. Brake damage and a blown tire during landing meant all future landings would move to Edwards Air Force Base until the shuttles could be equipped with nose wheel steering.

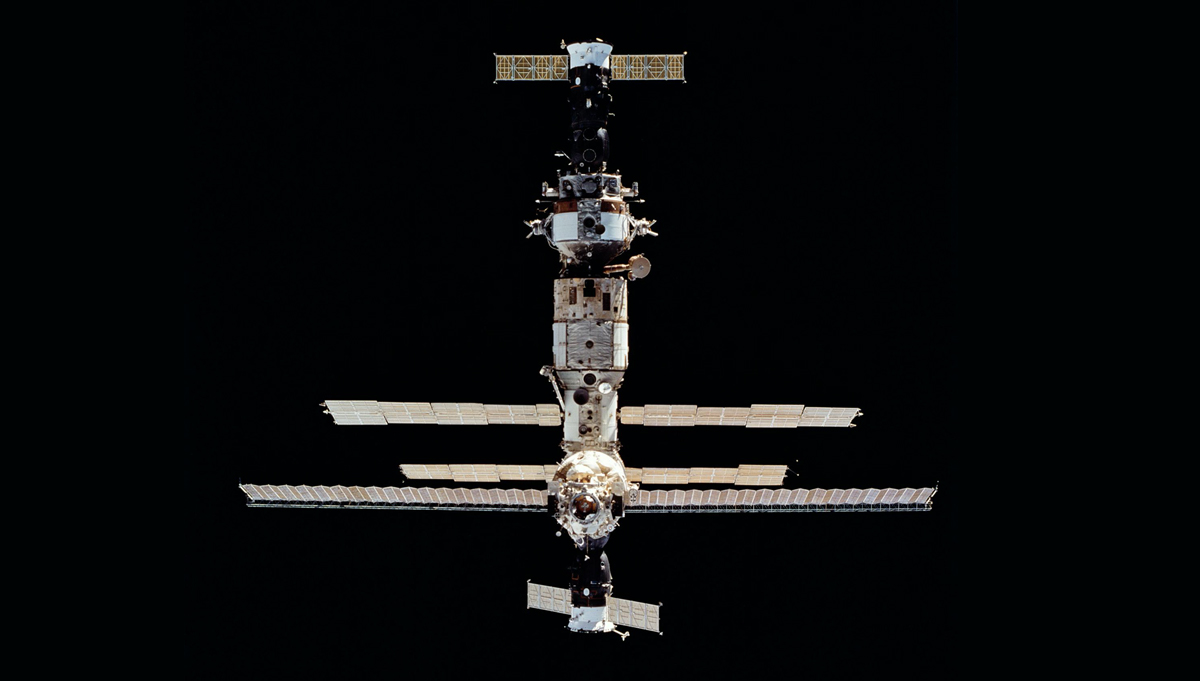

Visit APPEL KS’s Shuttle Era Resources Page to learn more about STS-51-D and the other 134 shuttle missions over 30 years, missions that deployed key satellites, repaired the Hubble Space Telescope, enabled important new research, and were instrumental in construction of the International Space Station. The Shuttle Era Resources Page also contains important resources on the Challenger and Columbia accidents and enduring lessons learned.