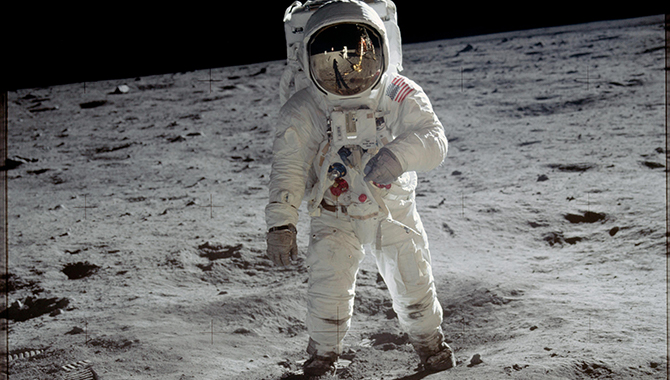

Bill Tindall (left) and Gene Kranz in Mission Control during Apollo 11.

Credit: NASA

History Office presentation highlights master integrator of Gemini, Apollo.

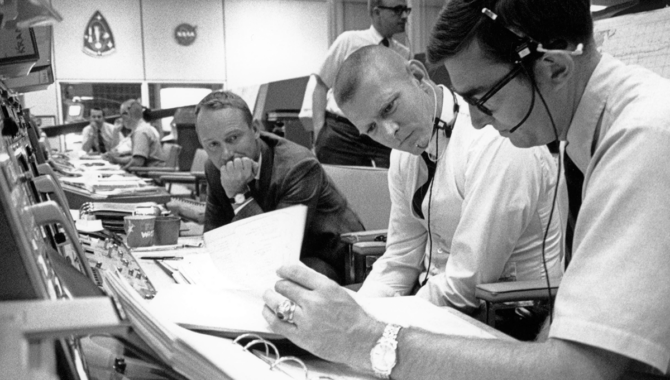

On July 20, 1969, as Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin were preparing to attempt the first human landing on the Moon, Flight Director Gene Kranz spotted Howard W. Tindall, Jr. in the viewing room of Mission Control. Kranz cleared space and told Tindall to sit with him at the console. Tindall at first declined but was persuaded to take the front row seat to history.

“I think that was probably the happiest day of his life,” Kranz recalled in an oral history. “A spectacular guy. … If there should have been a … plaque left on the Moon [for] somebody in Mission Control or Flight Control, it should have been for Bill Tindall. Tindall was the guy who put all the pieces together, and all we did is execute them.”

Tindall began his career at NASA’s predecessor, the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics at Langley Research Center, working with Langley’s wind tunnel. In 1961, at the beginning of the space race, Tindall transitioned to orbital mechanics and developing the mission plans that would make the theoretical concept of rendezvous in space a reality. Later, he worked with the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, overseeing software development, and then as chief of Apollo Data Priority Coordination.

Along the way, Tindall developed the reputation as an exceptional leader—extraverted and gregarious, friendly and humorous—who could comprehend incredibly complex material, develop strong teamwork among disparate and mercurial personalities, and identify the ideas that worked from the ideas that didn’t.

In February, NASA’s History Office held a Lunchtime Talk: Bill Tindall’s Leadership During Gemini and Apollo. John Goodman, an experienced aerospace engineer currently supporting the Orion spacecraft in Artemis missions, discussed Tindall’s many contributions to Gemini and Apollo and the key role a voluminous series of memos published between 1964 and 1970 played in the success of Apollo.

“Bill Tindall is probably best remembered by Apollo veterans for his memos called Tindallgrams. And the reason why we have so many of these Apollo Tindallgrams today is that the Apollo veterans saved them,” Goodman said. “Historian Andrew Baird has estimated that Bill Tindall wrote or dictated over 1,100 memos from 1964 to 1970 concerning Gemini and Apollo. Tindall used his memos to communicate with a broad audience that was eager to learn more about how the Apollo vehicles worked and would be flown, what decisions were being made, and the rationale and backstory behind those decisions.”

The meetings Tindall documented with folksy humor and disarming candor were sometimes 12-hours long, filled with the clashing, bold opinions of young technical professionals working through complex questions. Tindall’s meetings exemplified the best qualities of top leaders.

“At the start of a meeting,” Goodman said in February, “Tindall made sure everyone in the room understood what the objective of the meeting was. Then he facilitated discussions and navigated emotional arguments to find a consensus, even when data was incomplete or conflicting, making some reluctant to make a decision. These decisions, which were official due Tindall’s position, unified subsequent work to be done and helped people identify additional work that had to be performed.”

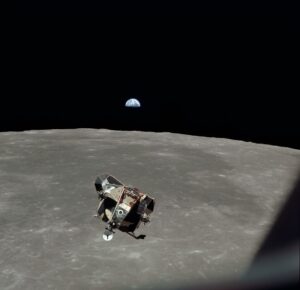

The Apollo 11 Lunar Module ascent stage, with astronauts Neil A. Armstrong and Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. aboard, is photographed from the Command and Service Modules (CSM) during rendezvous in lunar orbit. The Lunar Module was making its docking approach to the CSM.

Credit: NASA

The meetings were soon followed by a Tindallgram—a two- to three-page memorandum in a folksy style, recapping the key issues discussed, the progress made during the meeting, and next steps.

In one memo, Tindall alerted the team that Mike Collins, the Command Module Pilot for Apollo 11, asked if there was a reason he shouldn’t do active rendezvous navigation between Descent Orbit Insertion and Powered Descent Initiation. He wanted to run the P20 [on-board computer program] incorporating sextant and VHF ranging as a type of on-the-job training before he would have to do it later in the mission.

“This memo is to inform you that this activity will be included in the G mission timeline unless somebody comes up with a valid objection. Do you have one?” Tindall wrote.

On Friday, April 11, 1969—with the July 16 launch of Apollo 11 looming large—a Tindallgram with a total of 19 points and subpoints detailed a long meeting on April 5, in which the team resolved a number of open items relating to rendezvous during Apollo 11, including overburn, under burn, and items that emerged during simulations. “This memo is a list of them for the record. Some are trivial, some are really quite significant,” Tindall began. He concluded with, “And that’s how we spent Saturday.”

During the presentation, Goodman displayed a Tindallgram from June 1969, with a question from Apollo 12 astronauts Dick Gordon and Pete Conrad, noting that Tindall already knew which experts he could consult on the issue.

“Now what Tindall is doing is he’s involving the experts, but by writing this memo, he’s making a much wider number of people aware of the question and the issue. And he’s involving them in the eventual resolution of it. So, it becomes kind of an educational opportunity for people outside that small circle of experts. And it also opens the door for more people to provide commentary or bring up issues if they see them. Tindall encouraged people to think, learn, and communicate by showing humility.”

“…Everybody was ready to cooperate and work with Bill Tindall because you knew that his motivation was to get the job done right.”

When M. P. Frank III, a NASA engineer who was lead flight director for Apollo 14, Apollo 16, and the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, was asked during an oral history who stood out for him during Apollo, he immediately landed on Tindall’s name.

“He just amazed me what he ended up accomplishing. Pretty much through his own personal hard work and efforts,” Frank said. “…Everybody was ready to cooperate and work with Bill Tindall because you knew that his motivation was to get the job done right. He didn’t want any credit for it himself and he just wanted to make … sure that it got done right.”

To learn more about Bill Tindall, see Goodman’s papers Bill Tindall, Master Integrator of Gemini and Apollo, and Opportunities for Team Development Based on Lessons Learned from Spaceflight Operations.