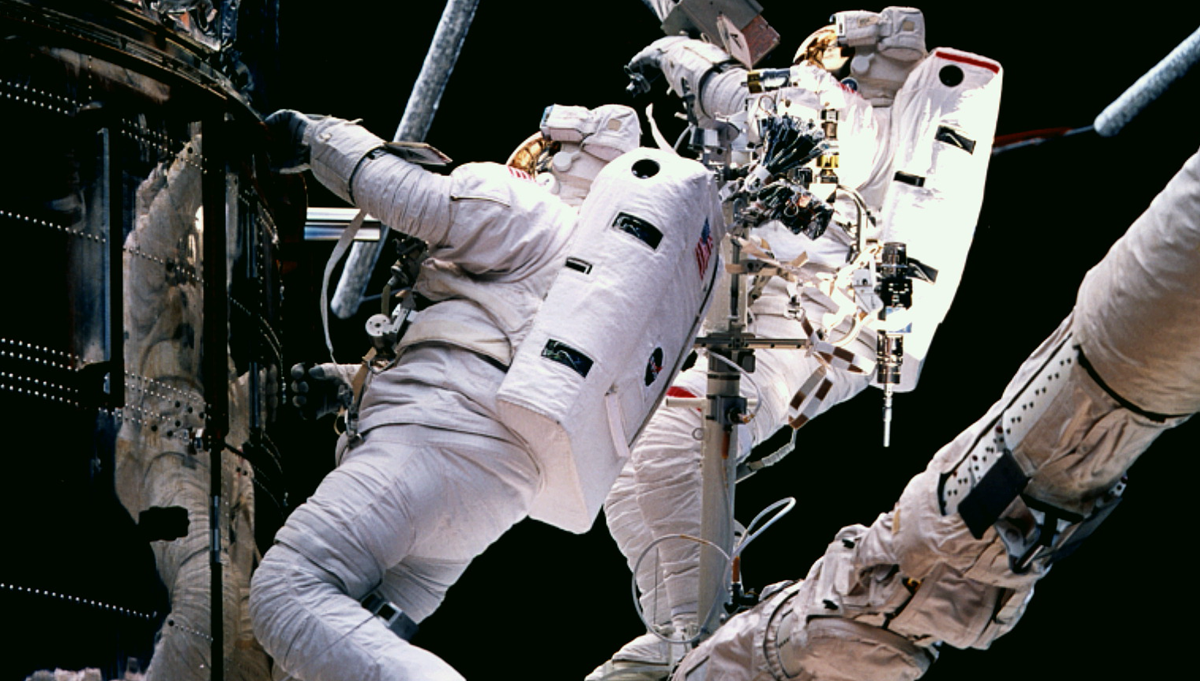

Payload Specialist John H. Glenn Jr., then a senator from Ohio, prepares to fly aboard STS-95, adjusting a video camera during training at Cape Canaveral. Mission Specialist Scott E. Parazynski looks on at right. Glenn’s two spaceflights were 36 years apart.

Photo Credit: NASA

‘The John Glenn factor’ draws large crowds to launch of STS-95.

Twenty-five years ago this month, in late October 1998, the area around Kennedy Space Center (KSC) came alive with a type of carnival atmosphere the Space Coast hadn’t seen in a quarter of a century, when NASA was launching the final Apollo missions to the Moon. The media descended on the area weeks in advance to speak with the astronauts who would soon launch aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery.

Next, the public began to arrive, filling hotels and restaurants, and scouting viewing areas. By the afternoon of October 29, an estimated 300,000 spectators packed the area’s beaches, causeways, and viewing areas. Traffic backed up on some area highways for five miles, where many resigned to watch the launch standing beside their gridlocked cars.

Venerable journalist Walter Cronkite, then 81, covered the countdown live on cable network CNN. At one point he was joined by Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, the second human to step on the Moon, and Charles “Chuck” Yeager, the first human to break the sound barrier. It was only the second time that a sitting president had attended a NASA launch.

When Cronkite asked President Bill Clinton what drew him to KSC that day, Clinton replied, “Well, of course, there’s the John Glenn factor. … I hope that all Americans share the exuberance that I feel today.”

As Clinton spoke those words, the crew of STS-95 was strapped in and ready for the raucous 8-minute ride to low Earth orbit. Commander Curtis L. Brown, Jr., was making his fifth spaceflight. To his right was Pilot Steven W. Lindsey, making his second spaceflight. Behind them, on the middeck was Payload Specialist Senator John H. Glenn, Jr. He, too, was making his second spaceflight. But unlike Lindsey, Glenn’s flights were separated by 36 years.

At 77, Glenn was by far the oldest astronaut to fly aboard the shuttle. Lindsey was just 18 months old when Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth on Mercury-Atlas 6. Brown was not quite 6 years old. Rounding out the crew were Mission Specialists Stephen K. Robinson, Dr. Scott E. Parazynski, and European Space Agency astronaut Pedro Duque. Dr. Chiaki Mukai served as a Payload Specialist.

Mercury-Atlas 6 lasted four hours and 55 minutes, orbiting the Earth three times. Glenn was called to fly the capsule manually, after a malfunctioning yaw attitude control jet forced him to turn off the automatic system guiding the flight. The flight had included a 30-minute test of manual flight, but the malfunction meant Glenn manually controlled the second and third orbits and re-entry. Glenn returned as a hero, addressing a joint session of Congress and riding in ticker-tape parades in his honor.

STS-95 crew portrait: Curtis L. Brown Jr., commander, appears at right center in the pyramid. Others, clockwise, are Steven W. Lindsey, pilot; Stephen K. Robinson, mission specialist; Pedro Duque, mission specialist (ESA), payload specialist Chiaki Naito-Mukai (NASDA); Scott E. Parazynski, mission specialist; and U.S. Senator John H. Glenn.

Photo Credit: NASA

“John Glenn’s flight sort of steered a lot of us kids into our interest in the space program,” recalled Phil Engelauf, NASA’s Flight Director for STS-95. “For me personally, it was really a big deal to have the honor of being the mission director on a mission with this icon of human space flight. At the same time, there was this huge contrast because it was a really intense mission from a science standpoint. And it was really challenging to get everything scheduled.”

The nearly nine-day mission included more than 80 science experiments. The crew released a free-flying spacecraft known as Spartan 201, which gathered data about the Sun’s corona, the solar wind that originates there, and the impact that wind has on satellites in orbit and weather on Earth. The crew also validated components that would be installed on the upcoming third Hubble Servicing Mission.

Glenn had been carefully monitored during Mercury-Atlas 6. Scientists had concerns if a human could focus their eyes in space or if the digestive system would function without gravity. By 1998, NASA had learned much about the effects long-term spaceflight has on the human body, and some of them—such as bone density loss, changes to the immune system, and sleep disruptions—are also experienced during the aging process.

STS-95 mission Commander Curtis Brown (left) and Payload Specialist John Glenn are photographed on the aft flight deck of Discovery during a press conference, Oct. 31, 1998.

Photo Credit: NASA

The spaceflight presented NASA with a unique opportunity to gather health data from a 77-year-old subject in space and compare that with data from younger astronauts and from Glenn’s flight 36 years earlier. Glenn and Duque performed experiments to quantify how the absence of gravity affects balance and perception, immune system response, bone and muscle density, metabolism, blood flow, and sleep.

Glenn, who was a U.S. Senator at the time, bonded with the crew, who admired not only his contributions to the early space program, but also his tenacious work ethic, personability, and willingness to share meal preparation and housekeeping responsibilities. Cronkite interviewed Glenn during the mission, asking if the U.S. space program was as far along as he had hoped it would be during his years as an astronaut.

“Oh, I always wish we were further along than we are, but we have a lot of demands on our budget,” Glenn replied. “I wish we were putting more money into it because I think it’s so valuable. This country got to be what it is because we put money into research and exploration. But we’ve made tremendous strides with science, and this, of course, is out on the cutting edge of science, with benefits for everybody right there in their homes across the country.”

STS-95 returned to Earth on November 7 after 134 orbits and almost nine days in space, landing at Kennedy Space Center. STS-95 made Glenn the only Mercury 7 astronaut to fly on the space shuttle.

Visit APPEL KS’s Shuttle Era Resources Page to learn more about STS-95 and 30 years of shuttle missions that enabled important new research and were instrumental in construction of the International Space Station. The Shuttle Era Resources Page also contains important resources on the Challenger and Columbia tragedies and enduring lessons learned.