Commander John W. Young (left), and Payload Specialist Ulf Merbold, enjoy a meal in the middeck of the Earth-orbiting Space Shuttle Columbia during STS-9. Credit: NASA

The shuttle program’s first crew of 6 works around the clock in a mission of firsts, then overcome daunting challenges to return safely.

In the months leading up to the launch of STS-9 in 1983, Brewster H. Shaw was outside Huntsville, Alabama, walking across the tarmac at Redstone Arsenal toward a NASA jet with John Young, Chief of the Astronaut Office. They were about to fly back to Houston, following mission training at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. Mission specialists Owen K. Garriott and Robert A. R. Parker were also returning in a separate jet.

Young had flown the jet to Alabama and put Shaw in the pilot’s seat for the ride home. Young was a veteran of Gemini III, Gemini X, and Apollo 10. He landed on the Moon during Apollo 16, and commanded the first flight of Space Shuttle Columbia, STS-1. Shaw was a test pilot on loan to NASA’s astronaut corps from the U.S. Air Force. The upcoming launch would be his first trip into space.

In this photo from 1989, Commander Brewster H. Shaw, wearing navy blue flight coveralls and helmet, sits in T-38A forward cockpit. Shaw, along with his fellow crewmembers, is preparing for departure from Ellington Field to Kennedy Space Center (KSC). Credit: NASA

“We did about a fifteen-second-formation flight briefing on the way walking out to the airplanes. That runway is narrow. So, we decided we wouldn’t do a formation takeoff. We would stagger our takeoffs. I understood that and I acknowledged that,” Shaw recalled in an oral history.

But when Shaw saw, from the corner of his eye, the other plane taking off while he was checking his instruments, instinct took over. He released the brakes, stroked the burners, and they were in pursuit. The quick action meant the planes had “exactly the wrong spacing” between them, with Shaw and Young caught in the first jet’s vortices.

“Dirty, dirty air,” Shaw recalled. “The next thing I know, we’re about twenty feet in the air and we’re at ninety degrees of bank, because the dirty wind kicked the airplane over. So, I’m standing on top rudder as hard as I can and I’ve got full aileron in, and from the back seat I hear this, ‘Brewster.’ This is John talking.”

“So, I’m still struggling with this airplane. The next thing I know, we’re in ninety degrees of bank the other way, and I got the other top rudder in and the aileron the other way. From the back seat I hear, ‘Brewster!’ ”

After Shaw wrestled the plane to clear air and got it squared away, he and Young flew to Houston in silence. When they landed, Shaw had a dilemma.

“I think to myself, ‘You’ve got to say something to John.’ But what do you say? And all I could think to say was, ‘God, John, I’m sorry,’ Shaw recalled.

Assuming he would be replaced as the Pilot on STS-9, Shaw spent the next day waiting on a call from Young. Whether Young was impressed with the skill Shaw used to pull the aircraft out of a bad situation, respected the candor of his apology, or was confident he could spot potential in rookie astronauts, the call never came.

“Bless his heart, he didn’t do that,” Shaw said. “So, I got to go fly it with John and the rest of the guys.”

On November 28, 1983, 41 years ago this month, NASA launched the Space Shuttle Columbia on STS-9. “It really put you back in the seat right away,” Shaw recalled of the launch, in a NASA video. “Kinda surprised me. The Gs are on you real fast. We made it to orbit, opened up the payload bay doors, deployed the radiators, put out the K-band antenna, and we were ready to operate in a really short time.”

The six crewmembers of STS-9 position themselves in a star bust-like cluster in the aft end cone of Spacelab aboard the Shuttle Columbia. Clockwise, beginning with John W. Young, are Ulf Merbold, Owen K. Garriott, Brewster H. Shaw, Jr., Byron M. Lichtenberg and Robert A.R. Parker. Credit: NASA

STS-9 was the first mission with a six-person crew. In addition to Young, Shaw, Garriott, and Parker, the crew included payload specialists, NASA astronaut Byron K. Lichtenberg and Ulf Merbold of Germany, the first astronaut from the European Space Agency to fly aboard the space shuttle.

STS-9 carried Spacelab into space for the first time. The science laboratory remained in the orbiter’s cargo bay during flight and facilitated complex experiments in low-Earth orbit. The team didn’t have to wait long for their first challenge—the shuttle’s hatch wouldn’t open.

“I remember thinking, ‘Holy smokes. This mission’s not going to go well if we can’t get into the lab,’ ” Shaw recalled with a laugh. “Looking at Owen’s and Bob’s faces, I remember thinking, ‘Boy, these guys are seeing their lives pass in front of their eyes, if we can’t get in there to do the stuff that they’ve been training for all these years to do.’ But we finally managed to get the hatch open. It took us a few minutes. But we did, and it was a very successful, very successful mission.”

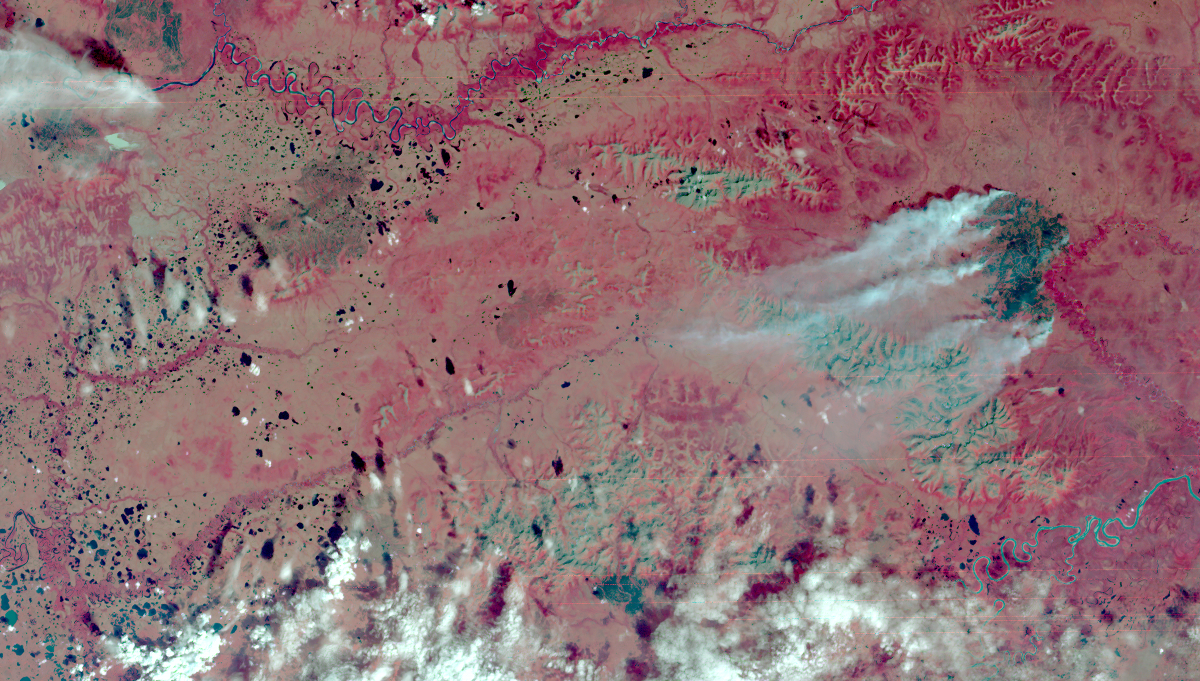

The team conducted more than 70 investigations across a variety of fields, including astronomy and physics, atmospheric physics, Earth observations, life sciences, materials science, space plasma physics, and technology. The work was divided into two, 12-hour shifts, with Young, Parker, and Merbold on one shift and Shaw, Garriott, and Lichtenberg on the other. NASA added a day to the mission to continue the science. Between 1983 and 1998, space shuttles carried Spacelab on a total of 22 missions.

December 8, the crew’s final day in space, was eventful. With the astronauts strapped into their seats for reentry, one of Columbia’s five General Purpose Computers (GPC) failed. The GPCs played a critical role in managing the shuttle’s operations during flight, performing 400,000 benchmark tests per second. Six minutes later, a second GPC failed.

“So, we ended up waiving off our de-orbit at that time,” Shaw recalled. “It was the end of John’s shift and John was tired, so he went down to take a nap. All of a sudden there starts this … bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang. The next thing, one of our three IMUs [inertial measurement units] fails.”

The Space Shuttle’s Inertial Measurement Units were critical navigation instruments used to determine the shuttle’s orientation, velocity, and position in space, helping to keep the shuttle aligned with its intended flight path and providing data that was critical for both automated and manual control.

After eight hours of troubleshooting, Mission Control guided Young and Shaw through a sequence that brought one of the GPCs back online. With that, Young was cleared to fire the shuttle’s Orbital Maneuvering System engines to begin his final descent from space.

“It sure is a delightful flying machine from start to finish,” Young recalled of the shuttle in a NASA video. “It’s hard to believe the orbiter weighs 110 tons, but it does. And we proved the capability to bring back on that mission over 21 tons of payload.”

Left to right are Payload Specialist Robert A. R. Parker. Parker is partially obscured by a deployed instrument of the fluid physics module at the materials sciences double rack. Merbold, a physicist from Max-Planck Institute in the Federal Republic of Germany, wears a head band-like device and a recorder as part of an overall effort to learn more about space adaptation. Both Spacelab 1 payload specialists wore the devices during most of their waking hours on this 10-day flight. Credit: NASA

It was a beautiful day at Edwards Air Force Base, Young recalled. He could see the dry lakebed from 60 miles out and spent his last descent admiring the shuttle’s crisp handling.

“Because of our problems we’d been up for a long time. Brewster had been up about 14 and a half, 15 hours. I’d been up about 20 and a half hours, I think. Even so, because we’ve had a lot of practice doing this kind of thing, it just seemed like ‘old home week’ getting back there and shooting that approach,” the veteran recalled of his last reentry.

Shaw went on to serve as Commander of STS-61B, the first flight of the Space Shuttle Atlantis, in 1985, and STS-28 in 1989. Following that mission, he moved into management positions that oversaw operational aspects of the shuttle program, ultimately serving as Director of Space Shuttle Operations, managing the development of shuttle elements—including the Orbiter, external tank, solid rocket boosters, main engines—and the facilities and planning required for mission operations.

Young remained as the Chief of the Astronaut Office until May 1987. He retired from NASA in 2004, after 42 years as an astronaut. “I’ve been very lucky, I think,” Young said.

Visit APPEL KS’s Shuttle Era Resources Page to learn more about STS-9 and the other 134 shuttle missions over 30 years, missions that deployed key satellites, repaired the Hubble Space Telescope, enabled important new research, and were instrumental in construction of the International Space Station. The Shuttle Era Resources Page also contains important resources on the Challenger and Columbia accidents and enduring lessons learned.