On Jan. 5, 1972, President Richard M. Nixon and Dr. James C. Fletcher, NASA Administrator, discussed the proposed Space Shuttle vehicle in San Clemente, Calif. The President announced that day that the United States should proceed at once with the development of an entirely new type of space transportation system. Credit: NASA

The nation chooses to reduce spending after Apollo, focusing on a versatile, reuseable spacecraft for low-Earth orbit.

In January 1972, as NASA astronauts John Young, Ken Mattingly, and Charles Duke were preparing for the April launch of Apollo 16, then President Richard Nixon, anticipating “a fitting capstone” to the Apollo program in the months ahead, issued a statement about the future of the U.S. space program.

“I have decided today that the United States should proceed at once with the development of an entirely new type of space transportation system designed to help transform the space frontier of the 1970’s into familiar territory, easily accessible for human endeavor in the 1980’s and [1990’s],” the statement began.

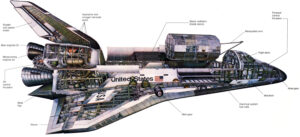

This illustration is an orbiter cutaway view with callouts. The orbiter is both the brains and heart of the Space Transportation System (STS). Credit: NASA

The entirely new type of space transportation system was the Space Shuttle, the first reusable spacecraft. The shuttle’s raucous 8-minute ride into low-Earth orbit would revolutionize space exploration, reducing the cost per launch compared to Apollo’s Saturn V rocket. And with a fleet of shuttles, the program facilitated as many as 9 launches per year.

“In short, it will go a long way toward delivering the rich benefits of practical space utilization and the valuable spinoffs from space efforts into the daily lives of Americans and all people,” the statement read.

“…The past decade of experience has taught us that spacecraft are an irreplaceable tool for learning about our near-Earth space environment, the Moon, and the planets, besides being an important aid to our studies of the Sun and stars,” the statement continued, emphasizing the benefits of a space program to life on Earth, including satellite communications, weather forecasting, natural resource management, and agricultural applications.

The Space Shuttle had been part of one option in an ambitious plan presented to Nixon in September 1969 by the Space Task Group (STG), which was chaired by Vice President Spiro T. Agnew. The STG included Thomas O. Paine, NASA’s third administrator—who served for 18 eventful months from March 1969 to September 1970—and Robert Seamans, who was then Secretary of the Air Force, but had been NASA’s deputy administrator from 1965-1968.

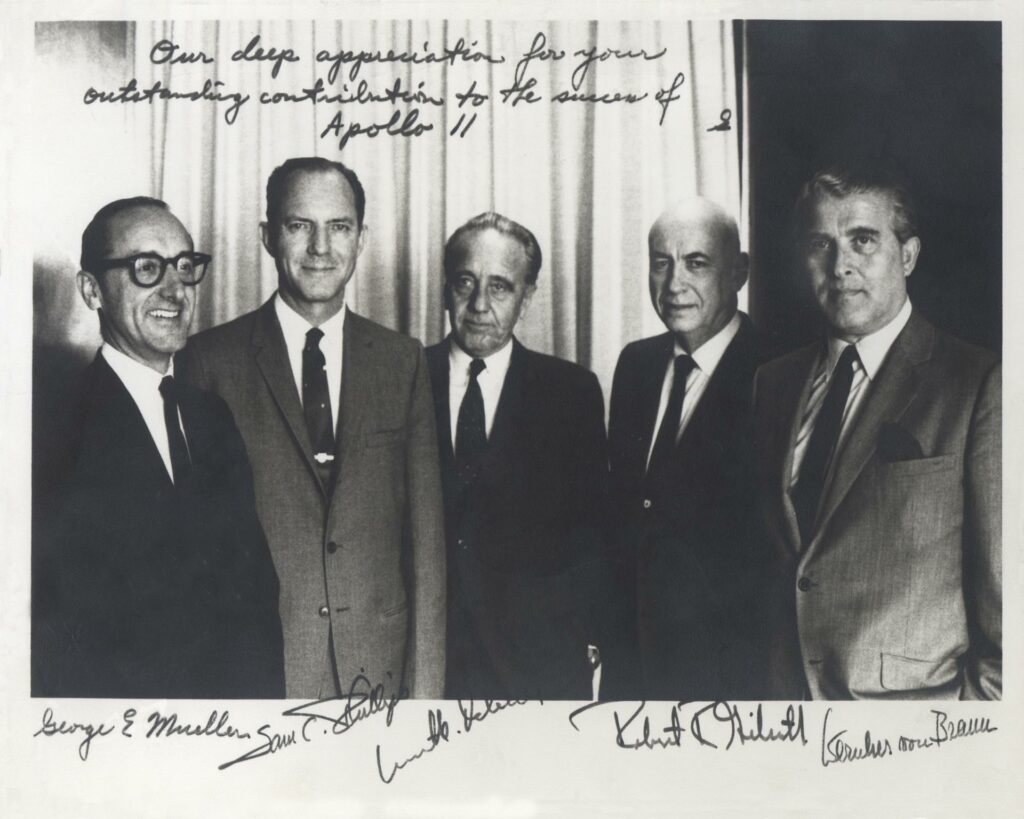

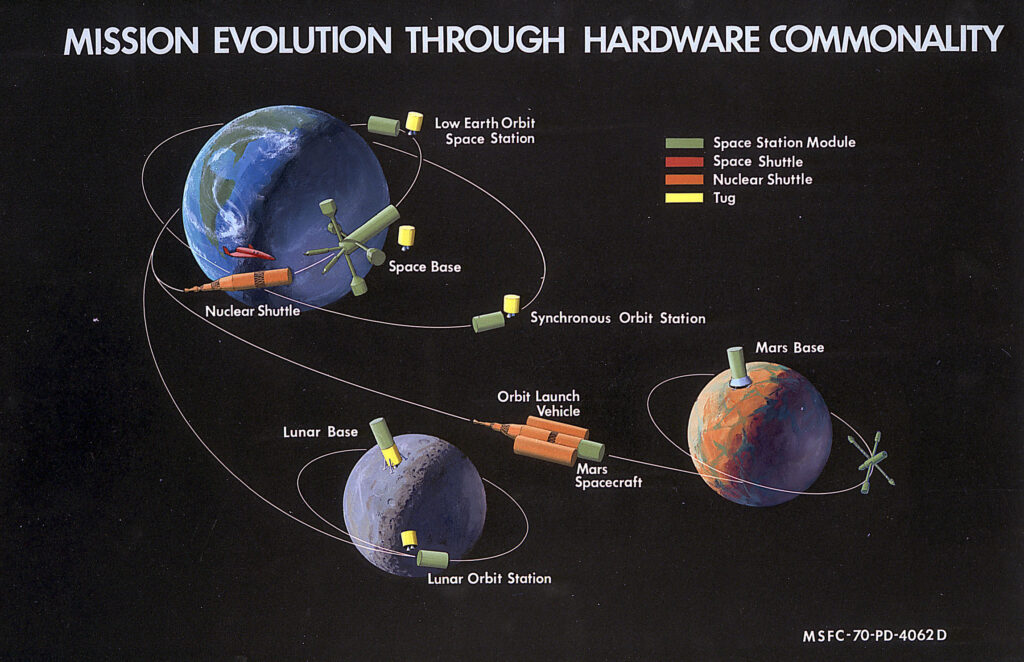

The work of the STG was informed by years of research and thought leadership by officials within NASA, including George E. Mueller, who led the Office of Manned Space Flight from September 1963 until December 1969. Mueller, a brilliant and fearless technical leader, advanced a future for NASA that envisioned space stations in both low-Earth orbit and cislunar orbit at the Moon, with several types of space shuttles and space tugs to travel between the outposts.

This historical photograph is of the Apollo Space Program Leaders. An inscription appears at the top of the image that states, “Our deep appreciation for your outstanding contribution to the success of Apollo 11”, signed “S”, indicating that it was originally signed by Apollo Program Director General Sam Phillips, pictured second from left. From left to right are; NASA Associate Administrator George Mueller; Phillips; Kurt Debus, Director of the Kennedy Space Center; Robert Gilruth, Director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, later renamed the Johnson Space Center; and Wernher von Braun, Director of the Marshall Space Flight Center. Credit: NASA

“…We set out to do a long-range plan following Apollo, and we started that about 1967,” Mueller recalled in an oral history. “One of the things that became apparent was that, first of all, we had to have a goal we were going to search for, which was our next goal. And then we began to lay in what it took to reach that goal. We started very early on looking at a space station as the next step in Apollo.”

Their investigation soon indicated that a single space station couldn’t foster enough significant research at that time to justify it as the next long-term goal of a space program that would soon send astronauts to the Moon. Rather, the team began studying a total space transportation system.

“We decided that … we needed to be able to have nodes in that transportation system so that you didn’t have to take everything all the way there and back again. So, the space station became the first node,” Mueller recalled. “Our plan called for a second node around the Moon as the next step in space, and then there are interorbital transfer vehicles and excursion vehicles for the Moon and back again. You had a complete transportation system like a railroad system, if you will, in space, made up of components to travel from one place to the other and carry the cargo on separate vehicles as you went.”

In this artist’s concept from 1970, propulsion concepts such as the Nuclear Shuttle and Space Tug are shown in conjunction with other proposed spacecraft. As a result of the recommendations from President Nixon’s Space Task Group for more commonality and integration in the American space program, Marshall Space Flight engineers studied many of the spacecraft depicted here. Credit: NASA

“And then that plan also said, ‘well, gee, that’s something we’ve already done, but we’re going to learn from that and then we’re going to put a node out around Mars, and we would move then from Earth orbit to Martian orbit. The energy required is not that much different from going to the Moon, when all is said and done. So that was the structure,” he added.

When the STG delivered its recommendations in 1969, a “Maximum Pace” option included multiple space stations, multiple shuttles, and a human mission to Mars launching in the mid-1980s. That option would have involved tripling NASA’s budget over the coming decade. The lowest option would have abandoned human space flight after Apollo 17 and relied on uncrewed missions to explore the solar system. The administration immediately signaled that neither of those options would be selected, then deliberated the path forward for more than two years.

A low-angle view captures early stages of the sixteenth launch of Space Shuttle Columbia on March 4, 1994. Credit: NASA

In the end, in the face of weakening public support for spending on the space program and reluctance in the U.S. Congress to embrace a bold commitment for a human mission to Mars, the space shuttle emerged as the next step in U.S. space exploration.

“The decision by the President is a historic step in the nation’s space program,” said Dr. James C. Fletcher, NASA Administrator, in a statement. “It will change the nature of what man can do in space. By the end of this decade the nation will have the means of getting men and equipment to and from space routinely, on a moment’s notice if necessary, and at a small fraction of today’s cost.”

The Space Shuttle Columbia, the first in NASA’s fleet, launched on STS-1 on April 12, 1981. At the controls was NASA astronaut John Young, who had been training for Apollo 16 when Nixon announced the shuttle program.

Visit APPEL KS’s Shuttle Era Resources Page to learn more about the 135 shuttle missions NASA flew over 30 years, missions that deployed key satellites, repaired the Hubble Space Telescope, enabled important new research, and were instrumental in construction of the International Space Station. The Shuttle Era Resources Page also contains important resources on the Challenger and Columbia tragedies and enduring lessons learned.