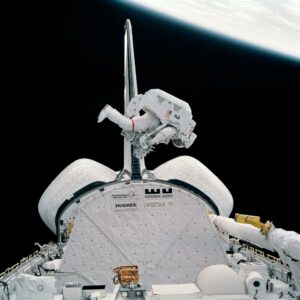

NASA Astronaut Bruce McCandless II reaches a maximum distance of about 100 yards from the Space Shuttle Challenger before reversing direction in his manned maneuvering unit (MMU) and returning to the spacecraft again and again during the nearly seven-hour untethered spacewalk. Credit: NASA

Long envisioned in science fiction, NASA’s Manned Maneuvering Unit was built to support critical tasks during the shuttle era.

At the zenith, he was merely a football field away. But when NASA astronaut Robert “Hoot” Gibson captured the moment on 70 mm film with a Hasselblad camera, astronaut Bruce McCandless II appeared incredibly small and alone—surrounded by the vast darkness of space, 170 miles above the Atlantic Ocean.

McCandless was testing a technology long imagined by science fiction writers, but one that had proven exceptionally challenging to engineer, develop, and deploy. NASA’s Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) represented the culmination of decades of research and innovation—a personal propulsion system designed to move astronauts effortlessly through the vacuum of space.

Test subject Fred Spross, Crew Systems Division, wears an Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU). The Gemini spacesuit, AMU backpack, and the Extravehicular Life Support System chest pack comprises the AMU, a system which is essentially a miniature manned spacecraft. Credit: NASA

Engineer Charles “Ed” Whitsett first began exploring the concepts that would lead to the MMU in the 1960s as a young Air Force officer. By the late decade, he was on assignment at NASA, where McCandless joined his office to work on the development of a “Buck Rogers-style backpack.” The project combined Whitsett’s research into the human body’s response to weightlessness with his work developing nitrogen gas propulsion systems.

NASA first tested a propulsion device during Gemini IV, when astronaut Ed White conducted the first American spacewalk. While tethered to the spacecraft, he used a small, hand-held jet device that released bursts of oxygen to help him maneuver. However, the device ran out of fuel after about three minutes, leaving White to move by pulling on his tether, which carried his oxygen and communication lines wrapped in gold tape.

In 1966, the U.S. Air Force developed a more advanced device known as the Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU), a self-contained rocket pack. The AMU was scheduled to be tested that year during Gemini 9A. But astronaut Eugene Cernan quickly became exhausted and overheated during the spacewalk, causing his helmet visor to fog up before he reached the AMU mounted on the back of the spacecraft. The AMU was dropped from the mission plans for Gemini 12.

With no immediate need for a self-contained propulsion device during the Apollo and Skylab programs, the development of an operational unit took a lower priority. Still, several maneuvering device designs were tested inside Skylab. In the mid-1970s, as NASA prepared for the Space Shuttle program, focus again shifted to the potential value of an MMU type device in space. When Whitsett joined NASA in 1977, he and McCandless used data from the Skylab tests to further improve the design.

In a 1975 study, Manned Maneuvering Unit Mission Definition Study Final Report, NASA envisioned astronauts using an MMU to tow objects, refuel satellites, and directly download data from them. The authors also proposed the use of advanced equipment such as wake detectors and cameras on an MMU to assist with complex tasks. These capabilities highlighted the MMU’s potential to support satellite maintenance, scientific research, and other critical space operations.

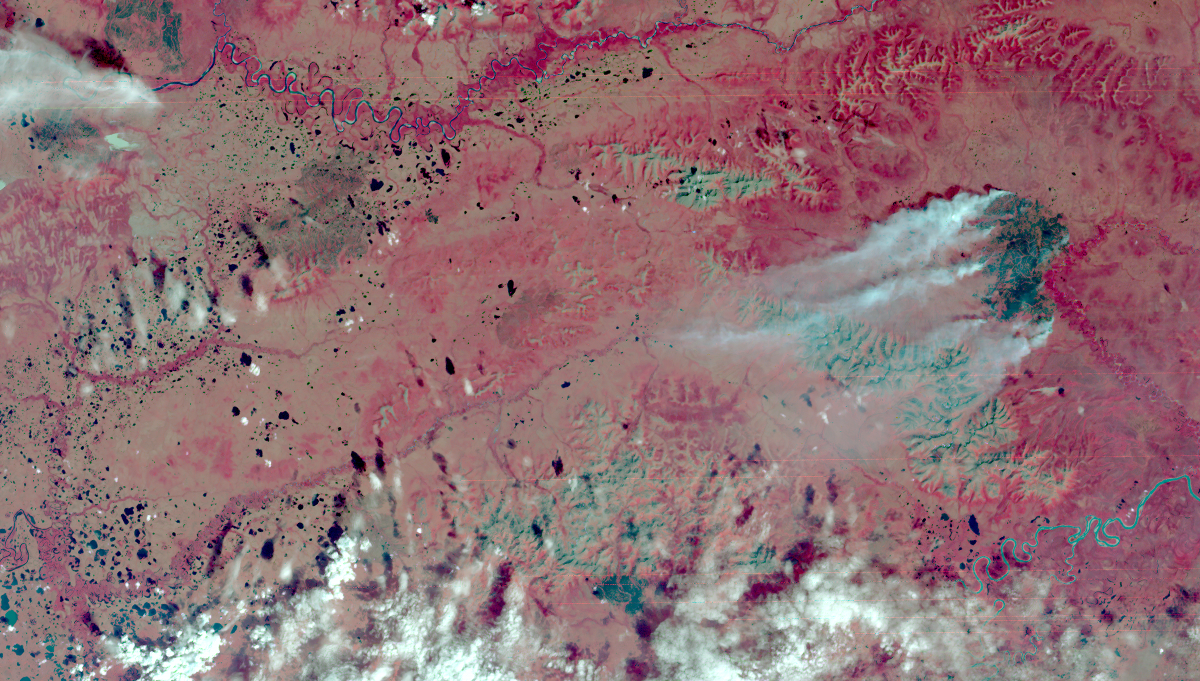

This 70mm frame shows astronaut Bruce McCandless II moving in to conduct a test involving the Trunion Pin Attachment Device (TPAD) he carries and the Shuttle Pallet Satellite (SPAS-01A) partially visible at bottom of frame. Credit: NASA

On February 7, and again on February 9, McCandless and NASA astronaut Robert L. Stewart passed through the airlock of the Space Shuttle Challenger into the payload bay, strapped into the MMUs, and walked untethered in space.

“That was a really nice reward for Bruce McCandless, who had worked on EVA [Extravehicular Activity] and worked with the MMU … and all the development and all the training and the engineering for years and years and years. It’s one of those just rewards that he got to be the first one to fly the MMU. He and Bob Stewart, of course, trained extensively on that to get to do that,” Gibson recalled of the EVAs of STS-41-B.

The final version of the MMU was far from a “Buck Rogers-style backpack.” At about 300 pounds, it was closer to the weight of a refrigerator. It was about 33.25 in. wide, 28 in. deep, and 50 in. tall. Its aluminum frame held two Kevlar wrapped aluminum tanks filled with nitrogen. Twenty-four small thrusters ejected the compressed nitrogen, allowing the astronauts to maneuver freely in space. They controlled their motions with two handles mounted on the device’s armrests. Motion-sensing gyroscopes automatically fired thrusters to maintain a set orientation.

With more than 300 hours of training on simulators, and a deep understanding of the redundancy that had been engineered into the MMU, McCandless was highly confident as he moved out into space. His wife, watching the test at Mission Control, was more apprehensive. In part to allay her fears as he moved away from the spacecraft, he said, “It may have been a small step for Neil, but it’s a heck of a big leap for me.”

Side close-up view of crewman in high-fidelity Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) / Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) mockup. Credit: NASA

“I’d been told of the quiet vacuum you experience in space, but with three radio links saying, ‘How’s your oxygen holding out?’ ‘Stay away from the engines!’ ‘When’s my turn?’ it wasn’t that peaceful,” McCandless recalled in a 2015 interview with The Guardian newspaper.

Feeling a mix of personal elation and professional pride, McCandless tested the pitch and roll controls as he moved 100 yards from Challenger and returned again and again, gauging his distance from the payload bay using a simple range finder. For six hours and 45 minutes, McCandless moved through space at nearly 18,000 miles per hour. Above him, he saw only darkness. And he was unable to sense the incredible speed he was travelling, until he looked down and saw Florida passing by at four miles per second.

“I don’t like those overused lines “slipped the surly bonds of Earth”, but when I was free from the shuttle, they felt accurate. It was a wonderful feeling,” McCandless recalled in the interview.

The MMU flew on two more shuttle missions. In April 1984, during STS-41-C astronauts James van Hoften and George Nelson attempted to use the MMU to capture the Solar Maximum Mission satellite and bring it into the orbiter’s payload bay for repairs and servicing but were unsuccessful because of an issue with the capture device. In November, during STS-51-A, astronauts Joseph P. Allen and Dale Gardner used the MMU to retrieve two communication satellites that failed to reach their correct orbits and return them to Earth.

The team that developed the MMU was recognized with the Robert J. Collier Trophy, awarded to NASA and builder Martin Marietta, for significant achievements in the advancement of aviation, with special acknowledgment of McCandless, Whitsett, and Martin Marietta’s Walter W. Bollendonk. To learn more about these shuttle missions, visit the APPEL Knowledge Services Shuttle Era Resources page.