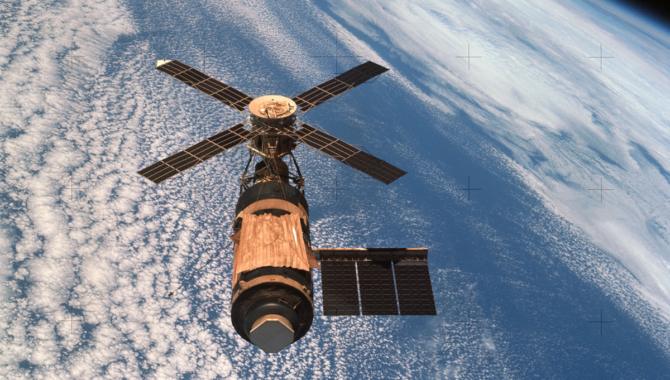

This photograph of Skylab, taken by the final crew to live and work there, shows the parasol sunshade that was deployed by the first crew to protect the orbiting workshop from the Sun and lower the internal temperature. Credit: NASA

Debates about what would follow the Moon landing lead to the development of NASA’s first space station.

In April 1966, NASA’s new Apollo Applications Program (AAP) was faced with a daunting question: What comes after the Moon? The United States had committed enormous resources to develop the technology to reach the lunar surface, but nobody was ready for Apollo to end there.

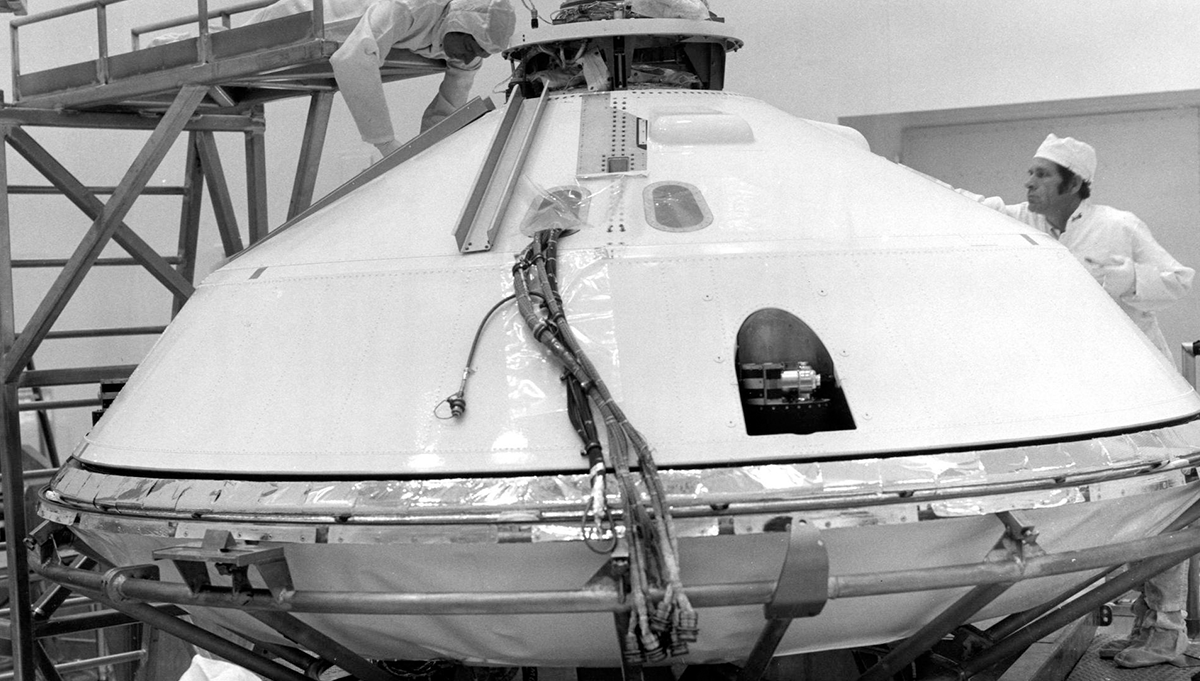

One proposal involved adding an airlock to the third stage of the Saturn V rocket, the S-IVB. On the Moon missions, this was a critical propulsion stage that put the spacecraft into Earth orbit and performed a second burn later in the mission to send the spacecraft on a trajectory toward the Moon. With its massive liquid hydrogen and oxygen tanks and rigid structure, the S-IVB was a significant piece of engineering.

Skylab 4 astronaut Edward G. Gibson works outside the Orbiting Workshop during a spacewalk in 1974. The Skylab-4 crew spent 84 days in the orbiting laboratory, a then record for longest spaceflight. Credit: NASA

“Some people … had always [had] thoughts of how to use the spent propulsion stages in Earth orbit. You expend the energy to put these stages in orbit [they thought], you ought to use them for something,” recalled Robert F. Thompson, in an oral history. Thompson was the program manager of the AAP from 1967-70.

“Someone came up with the idea of building an airlock so that the command module could turn around and dock with this airlock. Then you’d go through this airlock down into this empty hydrogen tank from this leftover stage that helped put you in orbit. The original thought was just to go down in there in an extravehicular activity (EVA) suit and float around in this big tank, just to see what it was like.”

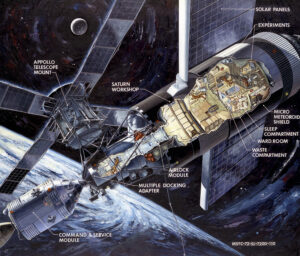

Meanwhile, astronomers were eager to get a large telescope into space, beyond the distortion of Earth’s atmosphere, to more clearly study the Sun and stars. In one AAP proposal, the empty bays of an Apollo Service Module bound for low-Earth orbit would be filled with solar telescopes—an instrument package that was known as the Apollo Telescope Mount.”

“So, the program was growing … in that kind of a hodgepodge fashion, and the medical people at that time were beginning to say, ‘Gee, we’re going to have fourteen days’ worth of experience of man in zero gravity or low gravity. We would be willing to … commit a man to flying twenty-eight days. We’d be willing to double it. It’s no more scientific than that. We can do it for fourteen days, we’ll try twenty-eight,” Thompson recalled.

“So now we’ve got a lot of people wanting to do solar physics, people wanting to have manned Earth orbit for longer periods of time. We’ve got this Apollo hardware with the airlock contract going. We’re trying to put this together in a program. Lots of meetings, lots of debates, lot of budget projections,” he added.

A key issue during the debates was should NASA pursue a “wet workshop” or a “dry workshop” strategy. The wet workshop was the original concept of repurposing a spent rocket stage on orbit. The crew of astronauts would have to adapt living space within and around the fuel tanks of the S-IVB. As the proposed missions under AAP grew longer and more complex, discussions began to include installing a bathroom, a kitchen, and even a refrigerator.

This artist’s concept is a cutaway illustration of the Skylab with the Command/Service Module being docked to the Multiple Docking Adapter. Credit: NASA

“So, this idea of taking this empty stage and making it a seaside cottage with a potty and a kitchen and so forth, got a lot of support, and that program began to grow…, because you had to build the refrigerator in such a way you could store it in here and have liquid oxygen in it. Then it would become a refrigerator. Or you had to store it outside and bring it in and plug it into something to make a refrigerator,” Thompson explained.

“But as we looked more and more to the wet workshop, particularly those of us here at the Johnson Space Center…, the more and more it looked like we were getting in over our head,” he added.

Because a mission to low-Earth orbit didn’t require the third stage, the dry workshop approach called for the S-IVB to be modified before launch. The massive liquid hydrogen tank was reinforced and modified to create living space and workspace for the crew. The smaller liquid oxygen tank was modified to hold waste. The workshop was about 58 feet long and 21 feet in diameter.

On May 14, 1973, NASA launched the dry workshop, which by then was known as Skylab. It was the final Saturn V rocket to ever lift off from Kennedy Space Center. It carried an ingenious repurposing of the S-IVB stage. With a mass of more than 168,000 pounds, it was the heaviest object placed into orbit at that time.

About 63 seconds into launch, as the Saturn V broke the sound barrier, Skylab’s micrometeorite shield tore away, likely because supersonic air rushed under the shield’s leading edge. This caused one of the solar arrays to deploy early and be ripped from the spacecraft, as the second array became pinned to the side by debris. It also damaged the interstage adapter that would separate Skylab from the S-II stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle.

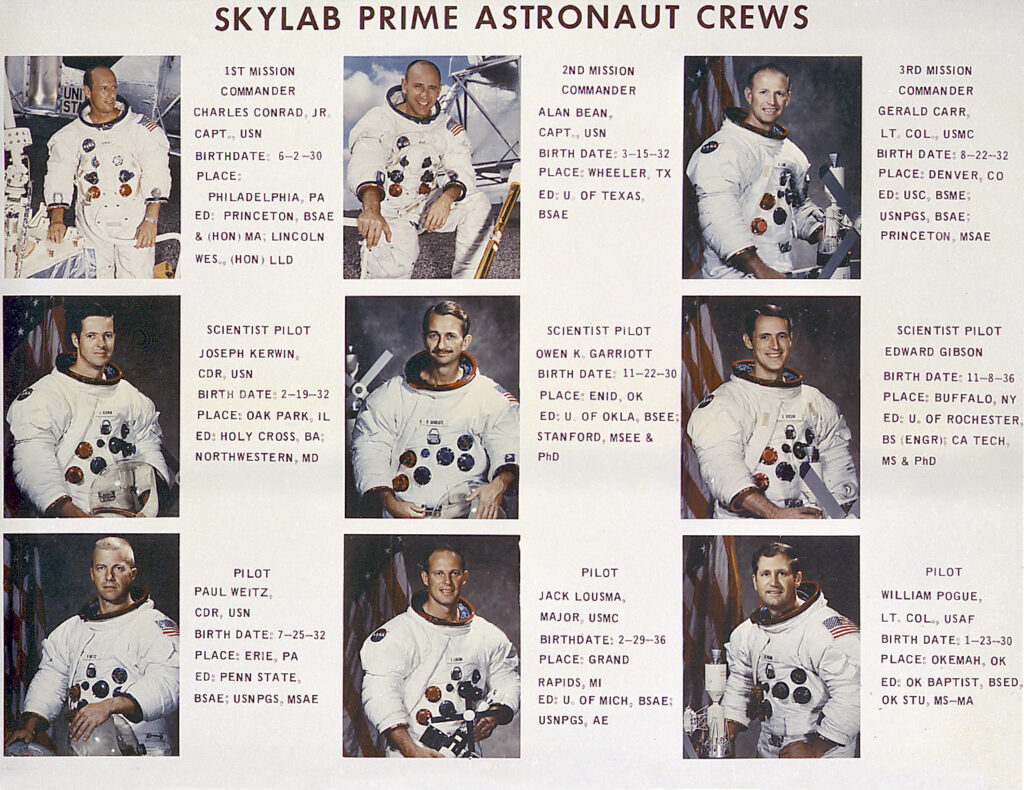

Three separate crews of astronauts lived and worked aboard Skylab, demonstrating how the human body adapted to long duration missions, operating telescopes beyond the distortion of Earth’s atmosphere, and conducting scientific experiments in the unique conditions of low-Earth orbit. Credit: NASA

NASA worked at a furious pace to develop the repairs that would protect Skylab from the intense heat of the Sun and allow it to generate enough power for crews to conduct the full slate of experiments. The first crew was delayed 10 days as NASA practiced the repairs. The first crew to visit Skylab—Commander Charles C. Conrad Jr., pilot Paul J. Weitz, and scientist Joseph Kerwin—successfully completed the repairs, then conducted 392 hours of experiments, took roughly 29,000 images of the Sun, orbited Earth 404 times, and performed three EVAs totaling six hours and 20 minutes. The mission was a success.

Three crews spent a total of 171 days aboard Skylab, photographing solar flares and coronal mass ejections, gathering important data about the effects of long-term space missions on the human body, and proving that humans could not only visit space, but live in it.

“Skylab was deliberately conceived as not a long-duration space station,” Thompson said. “There were never any plans to resupply the propellants, to carry it beyond the three missions that were planned. The way Skylab was left on orbit and then decayed and burned up was exactly the plan. It was a one-shot adventure, and that’s the way it had to be.”

Thompson left the AAP in 1970 to become the Manager of the Space Shuttle Program Office, a position he held until he retired from NASA in 1981. To learn more about Skylab, click here.