NASA Technology Transfer Program Executive Dan Lockney discusses the transfer of innovative space and aeronautics technologies for practical, terrestrial applications.

NASA’s Technology Transfer Program ensures that innovations developed for exploration and discovery are broadly available to the public, maximizing the benefit to the U.S. Lockney shares stories of how NASA technologies impact our everyday lives.

In this episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps, you’ll learn about:

- How NASA innovators can engage with Tech Transfer

- NASA’s role in development of cell phone cameras

- Highlights of the NASA Software 2019-2020 Catalog

Related Resources

NASA Technology Transfer Program

NASA Home & City | New Interactive Website Traces Space Back to You

New Technology Reporting System

NASA Software 2019-2020 Catalog

National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958

APPEL Courses:

Complex Decision Making in Project Management (APPEL-CDMPM)

Introduction to Project Management at NASA (APPEL-PM101)

Daniel Lockney

Credit: NASA

Daniel Lockney is the Technology Transfer Program Executive at NASA Headquarters. Lockney is responsible for agency-level management of NASA intellectual property and the transfer of NASA technology to promote the commercialization and public availability of federally owned inventions to benefit the national economy and the U.S. public. NASA has a long history of finding new, innovative uses for its space and aeronautics technologies, and Lockney is the agency’s leading authority on these technologies and their practical, terrestrial applications. He oversees policy, strategy, resources and direction for the agency’s technology commercialization efforts. Lockney started his NASA career as a contractor in 2004, converting to civil service in 2010. He studied American literature at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and creative writing at Johns Hopkins University.

Transcript

Dan Lockney: Everywhere you go you’re likely to find some NASA technology if you look for it.

The technologies we’ve developed have spanned so many different industries and have been around for so long and touched people’s lives in so many different ways.

What I like about Tech Transfer so much is there’s no day that’s the same, and we deal with the entirety of the agency’s technology portfolio.

Deana Nunley (Host): You’re listening to Small Steps, Giant Leaps – a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast featuring interviews and stories, tapping into project experiences in order to unravel lessons learned, identify best practices and discover novel ideas.

I’m Deana Nunley.

December marks the one-year anniversary of Small Steps, Giant Leaps. And on behalf of the APPEL Knowledge Services team I want to take a moment to thank you for listening and helping to make this podcast a success.

Our first 25 episodes have featured brilliant NASA experts on a wide range of topics — including astronaut training, spacesuit design, artificial intelligence, the Mars Opportunity Rover, Commercial Crew, the Apollo 50th anniversary, lessons learned from the Columbia accident, NASA’s Human Research Program, and the list goes on.

We’ve talked about a lot of cutting-edge NASA technologies this year — from aeronautics flight demonstrations to human space exploration, and it seems fitting to close out our series of podcasts for 2019 with a conversation about technology transfer. Our guest is NASA Technology Transfer Program Executive Dan Lockney.

Dan, thank you for joining us on the podcast.

Lockney: Glad to be here.

Host: Could you give us a quick summary of what NASA Technology Transfer is and how it works?

Lockney: Tech Transfer is one of NASA’s oldest missions. It was actually written into the Space Act of 1958. It says that technologies created for our space missions and aeronautics research need to get transferred to the public and come back down to the Earth in the form of practical terrestrial applications. Tech transfer is the formal process of identifying those innovations as we develop them and determining who else could use them and what the best way to get them outside of the agency would be.

Host: How do NASA program and project managers engage with the Tech Transfer Program?

Lockney: The first step to engage in tech transfer is with an invention disclosure. We own invention.nasa.gov and innovation.nasa.gov and a handful of other, e-NTR.nasa.gov, URLs to get to us. We also have a Tech Transfer office at every NASA field center. We conduct regular outreach. We’re easy to find if you’re looking for us.

The first step to get involved is to file an invention disclosure. If you have a new idea, a new concept, new technology, new method, new material, anything new that you’ve developed, try to talk to us about it. We’ll figure out who owns it, who else could use it, and the best way to get it out to those people.

Host: What makes technology transfer a vital part of NASA’s mission?

Lockney: We exist on the edges of NASA’s missions. The first mission that NASA has is to explore the universe and our place in it. So, you think of NASA missions as the human spaceflight, robotics, our aero research. That really is the core work that NASA does, but tech transfer is also in there and it’s part of what the public expects us to do.

If you ask the general public, a person on the street, “Has NASA technology benefitted humanity?” The answer is always “yes.” They may not know the specifics and, oftentimes, if they do know the specifics, they’ve got them wrong. We get credit for things like Tang and Teflon and Velcro, and we didn’t invent any of those. But there are thousands of technologies we did invent that improve people’s everyday lives.

So, the public expects we’re doing it, and that makes it kind of one of NASA’s core missions. It’s also written into the Space Act and several other federal laws and it’s in policy. Yet, tech transfer is a responsibility that we have to the American public to repay their investment in our privilege of working in this industry.

Host: When you look at space and aeronautics technologies that have been developed and successfully transferred during NASA’s 60-year history, what are some of your favorite stories?

Lockney: That’s difficult and I get that question a lot. It’s a little bit like asking a mother to tell you which child is her favorite. And unless you’re my mom, I think that would be kind of difficult. [Laughter]

It really depends on the person asking the question. The technologies we’ve developed have spanned so many different industries and have been around for so long and touched people’s lives in so many different ways.

If it’s the fetal heart monitor that we developed in the 1970s and into the ’80s, and you were able to determine that your pregnancy was sound back then and have that reassurance, you might think that that was one of the better ones. If you were one of the many people whose lives were saved or extended by one of the implantable heart devices that we developed over the years – there have been several – that might be the one you go to.

We developed the first infrared thermometers. So, if you were a baby who was able to have your temperature taken through your ear versus how they used to do it with babies, you’d probably be appreciative of that. I know my dogs also get the infrared thermometer in their ears and they much prefer that to the other method that they used to use at vets’ offices. So, it depends on who you are and where you’re coming from, which technology would be the best.

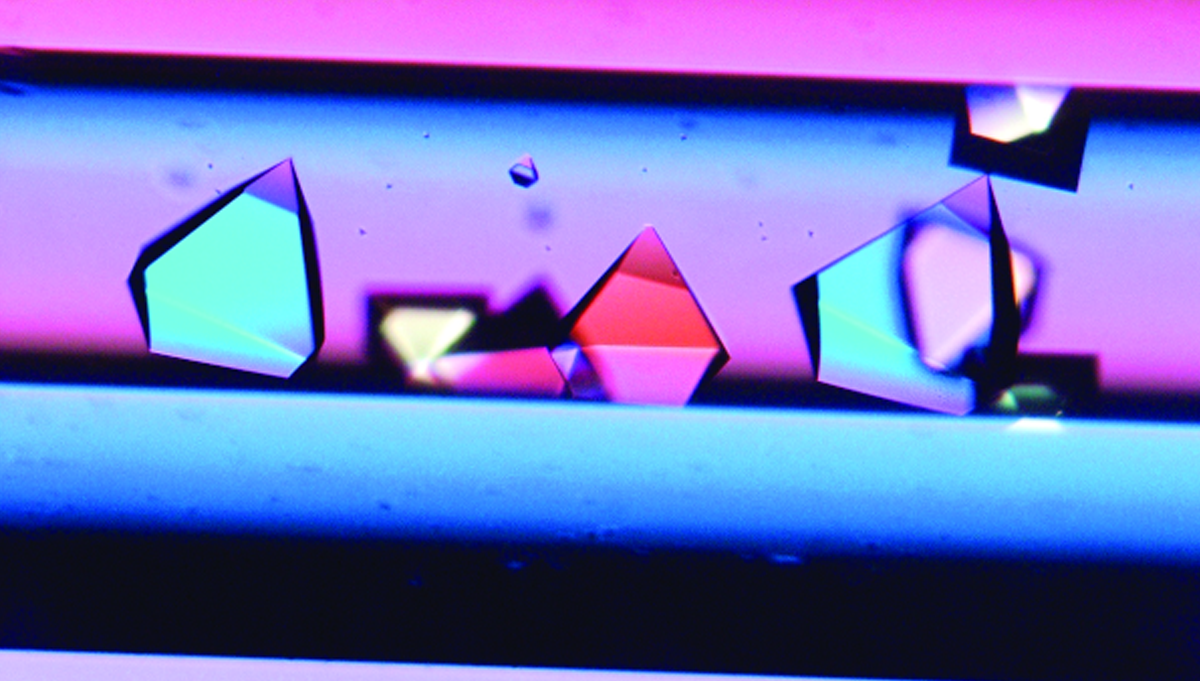

One of my favorites though is the camera in your cell phone. It’s an actual invention that NASA created. We own the patents on it still and we receive royalties from all the major cell phone manufacturers.

It was developed by a guy named Eric Fossum out at JPL. He was working on a high-resolution, lightweight camera that didn’t use a lot of energy. We developed this thing for satellite applications and we brought it back down to Earth. We were looking at it and we said, “Who could use a miniature camera like this?” We didn’t know. This was before cell phone cameras existed.

Our initial thinking was that this had a very small, narrow market, this miniature camera that we developed. We were thinking, specifically, spies could use it or secret investigators, like all the movies and TV shows you watched in the 1980s, where people would sneak into offices and open up the file cabinet and take the file of evidence down, and open it up and snap a little picture with the miniature camera. That’s what we were thinking. It turns out that’s a very small market and we were way off.

Nokia approached us and said that they thought they could put this camera in a cell phone. Quite honestly, we thought that idea was kind of absurd. “Who’s going to want that, a camera in a telephone? That’s ridiculous.” They were right, as evidenced by us all having and using one regularly.

So yeah, that’s kind of one of my favorites in the sense that it seems obvious now that everyone would carry this miniaturized high-resolution camera on them and, of course, it would be part of a phone, and I think of my phone more as a camera than I do a phone these days.

But we weren’t thinking of solving that problem. We were working on this entirely unrelated issue, and then came up with this device that now we consider ubiquitous and a necessity. So yeah, it’s those types of unexpected ones that we don’t know to predict that make a big impact that I’m excited about.

Host: This is just so interesting. I’d love for you to share some more stories. That obviously sounds like it was more of a space type of technology that was developed. What about aeronautics? Are there some that come to mind for you?

Lockney: If you’ve been on an airplane, which I imagine that many of you have, you can’t get on an airplane these days that hasn’t had significant impacts through our aeronautics research, whether it’s the chevrons or the engines or the blended upturned winglets, the kind of upturned 90 degree angle at the end of the wings, lightweight materials or the amazing work that we’ve done with understanding and improving how airplanes move about the national airspace.

But a kind of unexpected neat one that people don’t know about is Tempur-Pedic. That’s the mattress material that solved that problem that we all have, when you’ve got that glass of wine that you need to keep steady on your mattress somehow, but you also need to drop a bowling ball on the other end of it and you don’t want the wine to spill. You can use that Tempur-Pedic mattress, as their commercials demonstrated to us for a decade, that age-old problem.

That actually comes from, that viscoelastic memory foam that’s now a – we’re familiar most with it as Tempur-Pedic, but it’s a public domain technology now. That was developed as aeronautics research back in the 1960s by NASA as a vibration dampening for airplane seats. Pilots would be forced to sit in these vibrating chairs for long periods of time and it was contributing to their fatigue. We realized if we could reduce the vibration in their seats that you have less fatigue in the pilots. So that’s a common, ubiquitous, everyday example that people know about, but probably didn’t – and they knew it came from NASA, but they didn’t realize that it came from our aeronautics research.

Host: You’ve mentioned several technologies that are ubiquitous at this point. Are there also a lot of technologies that have been transferred that maybe everybody doesn’t know about, but they’re really making a lot of impact in certain areas of our lives?

Lockney: Absolutely. More often than not though – and this is the opposite answer of your question, and then I’ll answer your question properly. More often than not though, NASA technologies are so specific and they’re so niche that we end up making minor but significant contributions in a valve or a component that improves the manufacturing process or a lot of industrial applications.

So more often than that, it’s small businesses we’re working with to solve small problems. To get these heavy hitters is fairly rare, but it is always the fun part.

So, one example of another ubiquitous one, and this is one of my favorites, we had an inventor at Marshall Space Flight Center in the late 1970s/early 1980s named Frank Nola. I think his son is still at Marshall today. But Frank Nola developed this voltage controller device that reduced or increased the amount of energy used by an electric motor according to how much load was on that motor. It’s a simple energy-saving device that we’re using for mechanical operation.

We found a way to apply that same device to electric motors in escalators, elevators and moving sidewalks. It turns out that there’s only four companies in the world that make all of those — escalators, elevators and moving sidewalks — and since 1980, they’ve all been using the Nola voltage control device.

The idea behind it is pretty simple. You call an empty elevator and it uses less energy. But if you call a full elevator to your floor and it’s got six people in it, it uses energy to lift six people. But if it’s empty, it uses less energy. Prior to the implementation of this device, you would have to operate with an assumed full load in order to accommodate the off chance that it did have that full load.

So, you try to figure out how much energy savings that is over four decades now of every escalator, elevator and moving sidewalk. It’s phenomenal. Except in Wyoming. I just learned – this is totally off-topic, but I just learned that Wyoming only has two escalators.

Host: What?

Lockney: Yeah. This is probably not the right platform, but I’m telling everyone I know. I just think it’s fascinating.

[Laughter]

Host: We’ll see that on Jeopardy or one of these trivia shows one night.

Lockney: It’s like I can’t not share that one. So, we’re working on – you didn’t ask this question, but I’m on a roll now. It’s not just older technologies that are making an impact in our lives, but for some of these examples, it will take a couple years for NASA to develop a technology, a couple years for us to market it to industry and find a company that’s willing to adopt it and continue to adapt it for commercial applications. Then they manufacture and distribute and sell and it takes a while for these things to make inroads, and it might be 20-30 years before a NASA technology is so commonplace that we all recognize it and have it in our pockets, like the cell phone.

But there are newer technologies we’re working on, like a vibration dampening system that was developed for the SLS. It’s Ares, but I’m updating the story to make it SLS, but that’s not technically accurate – so a vibration dampening system for the big rocket we’re building. It was vibrating on the launch pad. This is all in simulation. It was vibrating and it needed to stop. It was vibrating at a frequency that would have been potentially catastrophic to the crew at launch.

Also, we couldn’t add a lot of weight to it. We couldn’t add a bunch of components. Because it needed to leave the planet, we couldn’t just strap it down or pack it in concrete or anything, and we couldn’t add a lot of features and components to it. So, we developed this series of baffles that are inside the liquid fuel tank, that control the slosh of the fuel during that launch phase, and then transfer that mass to the entirety of the vehicle and make it stop vibrating. We developed this technique and then got to thinking of who else could use this vibration reduction technique, and we realized that tall buildings are also rocket-shaped’esque and could use some help not vibrating in instances of, say, high winds or earthquakes.

So, we went up to New York and met with some developers of skyscrapers, high rises and towers, and ended up working with a company called Thornton Tomasetti, who now has an exclusive license for putting this in skyscrapers. They were building a building up in Brooklyn, which is not an earthquake-prone area, not particularly a high wind area, but the way the building was constructed was kind of modular units as opposed to scaffolding with wrappers around it, like a building is typically constructed. It’s kind of like Apartment 1, Apartment, 2, Lego style, put together. Because of that, it was particularly rigid, and also because of that building method, they weren’t able to get a typical, heavy, large, tuned mass damper into their design. So, they needed a simple structure that they could put on top of the building that would solve their vibration and sway issues.

So, we installed the device and it worked, and now they’re going to put it in every building that they’re making going forward. So that was kind of a fun win, and that’s something that we expect to see in skyscrapers going forward. I expect if I’m still in this job 20 years from now, which I would actually find delightful, 20 years from now I’d like to be able to say, “You know, there was a device we built back when we were going to the Moon the second time, and that device is now in every skyscraper.” I hope to be able to say that, and I could see me or somebody else being able to make that claim 20 years from now.

Host: It’s so fascinating how all of the space exploration and research impacts our daily lives. I know that one of the ways that Tech Transfer shares these stories is via the NASA Home and City website. I wonder if you might describe what’s offered on that site for us.

Lockney: Thanks. That was a lot of work and it was a lot of fun putting it together. We were trying to find a simple, compelling, visual way to impress upon people that everywhere they go NASA technology is in their everyday lives.

We did it through this kind of animated web feature. You can zoom into a city and you can visit the airport, a hospital, a sports stadium, a grocery store and several other buildings. You go inside of these buildings and it shows you these are all the ways, in the hospital, for example, that NASA technology has contributed to medical devices. It’s pharmaceutical robots. It’s advanced imaging techniques. It’s the heart implants that I mentioned. It’s lifesaving protocols developed to keep our astronauts safe. So, all types of ways that our technologies have spun off into the medical industry.

So you zoom out of that and you go into the airport and you can see the tower, the airplane at the tarmac, the ridged lines on the tarmac that prevent airplanes from hydroplaning, just simple grooves in the runway that we developed and now are commonplace on runways and highways. So, you find all the ways that we’re – not all, but significant ways that we’re in airports.

You zoom out of that and you go visit the house. Within the house, you go to the bathroom, the kitchen. In the bathroom would be anti-scald devices, so that the hot water doesn’t come out screaming hot, brass finish for bathroom faucets that are noncorrosive and last longer and keep your bathroom faucets shinier. There’s toothpaste that you’re able to swallow, which, granted, probably isn’t in everyone’s bathroom, but we developed it for astronaut applications, because you don’t want people to spit and then it floats into your crew mate’s face while they’re trying to sleep. That’s the reason why we do that, make them swallow a little toothpaste, but it’s useful for things like people who are bedridden or children. You want to have that device on Earth, too.

So, you go to the kitchen. You go to the living room. You can go play in the yard. You look throughout these rooms and it starts to impress upon you that everywhere you go you’re likely to find some NASA technology if you look for it.

Host: We will post a link to that website as well as the others that you mentioned earlier in the show. We’ll post that on our website at APPEL.NASA.gov/podcast.

We’re talking a lot about technologies that are being transferred, but NASA also makes advanced software required for space missions available to the public and recently released the 2019-2020 software catalog. What are some of the highlights of the latest edition of the catalog?

Lockney: We’re the only federal agency that has a comprehensive catalog of its software assets available for the public to use, but it’s also a great asset internally. We have about 1,000 codes from all 10 centers that are posted on software.nasa.gov. These are all modern, fresh. Everything is within about five years old, and these are things like Microsoft Project plug-ins, image analysis software, and actual engineering codes that our folks across the centers developed to do their jobs.

It would be difficult to say which specific ones are the most valuable, but I think the part that makes the entire collection valuable is that it’s so easily searchable. You can do keyword searches organized by business, application types. We’ll tell you what software requirements are.

Then the next part that makes it super-valuable is it’s all free. It’s free to the public. And for NASA users or government users, there’s an additional catalog of code that we wouldn’t necessarily share outside of the government. So, there’s ways that we can reuse the technologies that we developed and transfer them internally.

That’s a simple process. You can request the software online. It’s all processed out of a central location. Then we have a repository where we keep the code. When you send us a request for it, we look and make sure you are who you say you are and that the code is appropriate to give to you. Then we’ll send you a link and you can download it. That accessibility for 1,000 free NASA-developed engineering tools I think is the key.

Host: Are there other Tech Transfer resources that might be of interest?

Lockney: Yes. We put everything online. Everything is at technology.nasa.gov, and there are three major components of that website. The first is our patent portfolio, and that’s hardware that we’ve developed and patented. We only patent for the purposes of commercialization. We don’t patent for research prestige. We went to the Moon and I think that gives us plenty of prestige, at least for a couple more decades, and at least until we go back and even better this time when we get to Mars. We start have plenty of research prestige. We’ve already planted our flag there.

So, we only patent for the purposes of commercial potential, and with the belief that a patent is necessary for a company to compel the resources necessary to invest in bringing that technology to market. So, the first element of technology at technology.nasa.gov is our patent portfolio.

The next element is our software portfolio, which I mentioned. That’s 1,000 free codes that’s available internally and externally. And I should mention the patents. While they’re primarily for market application internal to NASA, I think it’s interesting to take a look at them, too, and still see what your colleagues at the other centers have come up with. The patents, sometimes you can view them as a proxy for knowledge and capabilities at the center. So, patents and software.

Then the third element on that website is our spinoff technologies, and those are all examples that we’ve recorded in the history of the agency of ways that NASA technology has benefitted the public. There’s a searchable database there. You can go in and type in your favorite keywords. You can search by state. You can search by center. And you can start to learn all the different ways that NASA is in your everyday life.

Host: When we consider spinoffs, it’s natural to focus on the end result and the benefits of all the innovation, but there’s a lot going on in the background. How does NASA use policy, strategy and resources to successfully commercialize technology?

Lockney: One of the biggest things we’ve done in the past couple of years is start looking at Tech Transfer as an agency-level function that is supported by the 10 field centers. This is kind of an inside baseball answer. But it used to be that before we had access to all of these tools like the Internet and exchange of information was so easy across the centers, it used to be that we considered each Tech Transfer office regional, and they primarily managed their own portfolios and worked as best they could outside of their center gates.

But now that we have the ability to reach anyone in the world through websites, through newsletters, through online marketing initiatives, we’re able to really reach a broader audience. With that comes the realization that the technologies we developed are geographically agnostic, and that people anywhere around the country especially are able to benefit from the things we’ve developed. So, we’ve been using 21st century technology and the agency’s emphasis on consolidation and centralization as policy guidance for improving our program.

Host: You sound like you really enjoy your work. What’s the best part of your job?

Lockney: I’m torn. I’ll be direct with you. Sometimes I do love my job. I always love my job. Sometimes when people ask why I like it so much, I get anxious that they’re going to try to take it from me or that somebody is going to catch on that I’m having too much fun. So, I usually say, “Well, you have to work with the lawyers a lot. There’s a lot of legal stuff involved,” and that scares people off. But, to be honest, the patent counsel at the centers, they’re our partners in this work and they’re actually great people to work with.

What I like about Tech Transfer so much is there’s no day that’s the same, and we deal with the entirety of the agency’s technology portfolio. So, I’m working with technologies ranging from new medical advances to new materials, and then industries from automotive to manufacturing. There’s policy work. There’s outreach. There’s a whole host of different activities you get to do and I’ve never had the same day twice here.

Host: That sounds like so much fun. It’s been great having you on the show today. We really do appreciate you taking time to talk with us, Dan.

Lockney: Hey, thanks for having me. This was a lot of fun.

Host: Links to topics mentioned on the show are available at APPEL.NASA.gov/podcast along with Dan’s bio and a transcript of today’s episode.

A quick programming note: This is our last episode for 2019. Our next episode is set for Wednesday, January 8, and we’ll look forward to reconnecting with you then.

On behalf of APPEL Knowledge Services, I want to wish you happy holidays and again thank you for listening to Small Steps, Giant Leaps.