By Karen Halterman

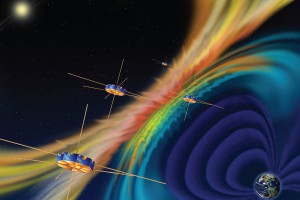

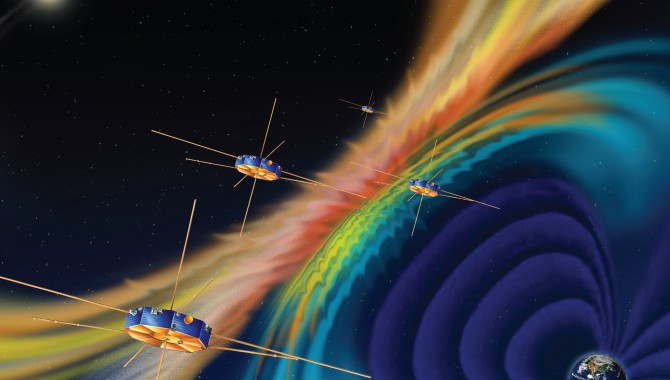

The Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission, a scientific satellite–development project managed by the Goddard Space Flight Center, is both an in-house project and a contracted one. The four MMS spacecraft are being developed by Goddard; the 100 MMS instruments are being developed under contract to Goddard. MMS offers examples of the advantages and disadvantages of both kinds of work, and the challenge of combining the two.

MMS is a NASA Science Mission Directorate heliophysics mission intended to gain an understanding of the universal process of magnetic reconnection, in which energy in magnetic fields is converted into particle kinetic energy and heat. The mission consists of four identical satellites, each with a payload of twenty-five instruments, that will circle Earth in highly elliptical orbits to measure magnetic fields, electrical fields, plasmas, and energetic particles. The satellites, flying in a tetrahedron formation as close together as 10 km, will take measurements in three dimensions with unprecedented resolution. Launch of all four satellites on one Atlas V is scheduled for August 2014.

Contracted and In-House Work

Most of NASA’s funding is spent on contracts. Large corporations, universities, medium-size companies, small businesses, research institutes, and consultants work under contract to NASA to provide rockets, space hardware and software, aeronautics research, scientific analysis, ground-system development, and resources for the myriad activities that NASA undertakes. Some of NASA’s responsibilities are inherently governmental and cannot be contracted, but some development items that could be contracted are carried out by NASA employees.

As explained in the NASA Strategic Plan, the agency needs to maintain the institutional capability and core competency of its workforce by performing some of the hands-on work itself. At Goddard, most satellite projects go to prime contractors, but some are developed in house—the spacecraft is designed, manufactured, and tested by Goddard civil-servant engineers. In-house projects provide the workforce with the personal experience necessary to oversee the development of contracted work. Support-service contractors augment the civil servants’ work, providing business and engineering expertise, including configuration management and mechanical engineering.

As explained in the NASA Strategic Plan, the agency needs to maintain the institutional capability and core competency of its workforce by performing some of the hands-on work itself. At Goddard, most satellite projects go to prime contractors, but some are developed in house—the spacecraft is designed, manufactured, and tested by Goddard civil-servant engineers. In-house projects provide the workforce with the personal experience necessary to oversee the development of contracted work. Support-service contractors augment the civil servants’ work, providing business and engineering expertise, including configuration management and mechanical engineering.

In 2006, NASA Headquarters assigned the development of the MMS spacecraft as a Goddard in-house development. All MMS instruments will be developed under a single contract by Southwest Research Institute.

In-House Development

Under the management of the MMS project, the Goddard Applied Engineering and Technology Directorate (AETD) will design, manufacture, and test the four MMS spacecraft and integrate them with the four instrument suites. MMS spacecraft development involves configuration-controlled documents and signed work agreements between the MMS project and AETD, but there are no contracts associated with in-house development. From the project management perspective, there are pluses and minuses to in-house spacecraft development.

Advantages

- Being internal to Goddard, the spacecraft team is physically located at the same place as the project and knows the Goddard culture. Communication between the project and the spacecraft team is enhanced by this proximity and common frame of reference. Misinterpretation of technical terminology, which sometimes varies among NASA centers, is minimized. For example, the MMS spacecraft team knows what “protoflight testing” entails, but the members of the MMS instrument team had to learn the Goddard definition of this term. Face-to-face discussions between the project and the spacecraft team happen every day. The project is in daily contact with the instrument team through teleconferences and e-mail, but in-person meetings occur less often, on average once a month.

- Compared with the lengthy process of formal contract direction, major technical and programmatic changes can be carried out more quickly by an in-house team. Once the project’s Configuration Control Board has approved a change that affects cost, schedule, or technical performance, the Goddard spacecraft team can immediately move forward with the new configuration. The instrument team, on the other hand, may need to wait for the contract modification in order to implement the change.

- Regular meetings with Goddard senior management are used to discuss status, address issues, and give the project some influence over the in-house work. Goddard senior management has helped the MMS project resolve facility-usage conflicts with other projects. By contrast, contracts can be bumped by higher-priority contracts. A Goddard project cannot override a DX classification— military programs judged to have the highest national priority—which permits military activities, such as buying electrical and electronic engineering parts needed in satellites, to take precedence over NASA civilian work.

- The Goddard workforce—from senior engineers leading subsystems to journeymen engineers developing designs to fresh-outs tackling hands-on testing—gains the practical experience of spacecraft development from concept through launch. Of course, the contractor’s workforce also gains experience, but this knowledge may not be applied to future Goddard missions.

Disadvantages

- As government employees, the Goddard spacecraft team tends to be less focused on cost control and meeting deadlines than industry counterparts who are accustomed to meeting contract requirements. With launch several years in the future, some members of the team need regular reminders about the importance of schedule performance.

- The NASA accounting system and financial reporting requirements are not conducive to large in-house projects. For example, NASA budgeting and monthly financial reporting require civil servant labor costs to be reported separately from other costs, but earned value management requires civil servant labor to be included in the appropriate work breakdown category. Hence, the MMS project must perform financial planning and reporting of the same cost data more than one way—a duplication of effort.

- AETD seeks to advance spaceflight technology, a commendable goal, but MMS is cost constrained like all projects. Occasionally, the project must temper the zeal of spacecraft engineers to experiment with new technology when an existing design meets requirements, costs less, and is less risky to build. MMS engineers have expressed interest in using composite materials, nanotechnology, and newer flight computers, for example. The project rejected these ideas as being more expensive or not mature enough for the mission.

- Components of the spacecraft that meet mission requirements and are commercially available will be competitively procured. It does not make sense to reinvent flight-proven items such as transponders, batteries, and thrusters. This means, though, that in-house development includes contracted items prone to the accompanying disadvantages of contracted work.

Contracted Mission

The MMS instruments are being developed under a Goddard contract with Southwest Research Institute, which leads a team of subcontractors and international partners that collectively will build 100 instruments for the mission. As with all Goddard contracts, NASA provides the requirements, funding, and oversight. The Southwest Research Institute team designs, manufactures, tests, and delivers the instruments to the MMS project. The project reviews the design and contract deliverables, provides technical direction and the interfaces to the spacecraft, works with the instrument team to resolve issues, and monitors technical progress, schedule, and costs. From the project management perspective, there are pluses and minuses to contracted missions.

Advantages

- While the project is ultimately accountable for all project activities, the contractor is fully responsible for producing the deliverables of the contract. The contractor directly manages the work; identifies, hires, and assigns the people with the necessary skills for the work; procures the parts and materials; and provides facilities to build and test the flight hardware. Since the MMS instruments are being acquired through a single contract, Southwest Research Institute is responsible for all of them, including those developed by its numerous subcontractors.

- Contractors selected to develop entire satellites or complex instruments generally have the people, experience, and infrastructure needed for such complex engineering efforts. As a result, a small NASA team is sufficient to monitor the contractor’s progress. Only a handful of the MMS project staff is dedicated exclusively to the administration of the Southwest Research Institute contract.

- The contractor, usually following a hard-fought competition to win the contract, is motivated to succeed in order to maintain a reputation in the aerospace community, pursue future government work, and earn profit for stockholders. Award fee contracts, which pay costs plus additional payments that depend on how well the contractor met specified performance goals, are particularly effective in providing periodic feedback to contractors and identifying areas for improvement. (In this particular case, award fee evaluations are not an available MMS management tool because Southwest Research Institute is a nonprofit organization with a cost plus fixed-fee contract.) As the home institution of the MMS principal investigator, Southwest Research Institute is committed to the science and the mission.

- When the contract ends, NASA does not have responsibility for placing the contractor’s employees into new jobs or keeping the contractor’s facilities in use.

Disadvantages

- The procurement of NASA flight hardware–development contracts is a lengthy process. Preparing all the documents needed to release the request for proposal, conducting the source selection, and negotiating the contract typically take more than a year. After the contract is in place, it still takes a long time to execute contract modifications because changes must be approved by the project’s Configuration Control Board and the center’s procurement and legal offices. If a major modification to the MMS Southwest Research Institute contract were needed, it would take several months to execute, possibly affecting the project schedule.

- Regardless of the best efforts to write complete and accurate specifications and statements of work, these documents inevitably have ambiguities. Disagreements about what is in scope and out of scope can lead to protracted arguments, increased costs, and even legal disputes. The contractual relationship between the MMS project and Southwest Research Institute is a good one, but now and then different interpretations arise, such as the extent of IT security requirements.

- At times, NASA may need to help the contractor; for instance, by providing specialized expertise. Some universities on the MMS instrument team do not have the robust quality assurance programs required to develop flight hardware. The project will provide mission assurance assistance to the MMS instrument contract as needed, which must be covered by the project budget.

- Business cycles and the overall state of the economy can adversely affect contractors. Most NASA contractors also support the Department of Defense; downturns in defense contracting may result in layoffs or closing of plants that affect NASA work, relocating it to other locations or increasing indirect costs stemming from a smaller business base. Takeovers, mergers, and sales of company divisions can also negatively affect NASA through loss of corporate knowledge, low morale, or changes in policies and procedures. The period of performance of the MMS instrument contract is long (it started in 2003 and ends after MMS on-orbit operations have finished in 2018). There have been and probably will continue to be changes in the corporate make-up of the instrument team. Universities on the MMS instrument team are also affected by the economy, as less state money is available during hard times, which could result in hiring freezes or less funding for labs and equipment.

The Best of Both Worlds

Both in-house and contracted approaches can be successfully used to develop flight projects. As suggested here, both approaches have significant strengths and significant potential weaknesses. As the MMS mission proceeds toward its scheduled 2014 launch, management will continue to try to capitalize on the advantages of both the in-house and contracted aspects of the project and minimize the disadvantages.

About the Author

|

Karen Halterman is the MMS project manager. Previously, she was the project manager for the Polar Operational Environmental Satellites project, a fully contracted mission. |