Photo Credit: Steve Garner

By Pedro C. Ribeiro

“Unfortunately, my King … here I am, unwilling and unwanted … because I know that no one ever welcomes a bearer of bad news.” —Antigone by Sophocles, circa 442 BC

“It is pardonable to be defeated, but never to be surprised.” —Frederick, the Great

Many failed projects provide early warnings that they will run into trouble, but these signs are often ignored. They fly under the organization’s risk radar, evading even sophisticated risk management processes. Organizations end up not recognizing early signs of failure until nothing can be done other than trying to manage a crisis.

The Good and Bad News About Project Failure

Projects may fail for many reasons. Common causes range from unrealistic expectations and unclear requirements to inadequate resources and lack of management support. Whatever the reason for a specific project failure, we should ask ourselves if it was a complete surprise for all involved, an outcome no one could possibly have imagined. Were 100 percent of the people involved in the project blind to the signs of an impending crisis?

The good news is that failure is rarely a complete surprise. Almost invariably, some people perceive the danger and try to warn the organization. Sometimes warnings from outside the organization signal trouble ahead. In other instances, the grapevine—the organization’s informal communication network—talks about it in the cafeteria or by the water cooler. According to research (see the Silence Fails report of 2006), up to 90 percent of employees involved in a project may recognize far in advance when projects are headed for failure.

The bad news is that 71 percent try to speak up about their concerns to key decision makers but do not feel they are heard, and 19 percent don’t event attempt to speak because they already know they will not be heard. The result: important risks are unnoticed or ignored until it is too late. Then the project suddenly collapses, leaving management wondering what went wrong. When the project is a large one, they may first learn about the failure from the news media.

Postmortem analyses, inquiries, and audits of failed projects often uncover streams of unheeded warnings in the form of letters, memos, e-mails, and even complete reports about risks that were ignored, past lessons not learned, and actions not taken—a failure of leadership that creates the conditions for a “perfect storm” of problems that could and should have been prevented, but nevertheless catch leaders by surprise.

Harvard Business School professors Max Bazerman and Michael Watkins apply the term “predictable surprise” to an event that takes leaders by surprise despite prior availability of the information necessary to anticipate the event and its possible consequences. I define “predictable project surprise” as an event characterized by sudden project status change or a discontinuity in a project’s expected or actual result that takes management by surprise when project team members or sources outside the organization tried to warn the organization about the danger.

Predictable project surprises can result from unmanaged differences in project risk perceptions.

Risk-Perception Gaps and Predictable Project Surprises

Risk perception is the subjective judgment we make about the characteristic, severity, and likelihood of a risk. It varies from individual to individual and from group to group. Education, experience, level of expertise on a specific subject, psychological traits, cultural context, and even the way risks are described all influence how we perceive the riskiness of a given situation. There has been a considerable amount of empirical research undertaken about why we perceive risks differently. Differences in risk perceptions are a fact of life and a strength in well-managed multidisciplinary teams, since they mean that some people will be aware of risks that others cannot see.

Look at the photo above. Depending on previous knowledge of the context, information, perspective, training, and expertise about scuba diving with sharks, we may have different perceptions about the inherent risk of this situation and our ability to cope with it.

Even perception of so-called “black swans”—high-impact, low-probability events—depend on the observer. According to Nassim Taleb, author of The Black Swan, what may be a black-swan surprise for one observer is not for another. A black swan is something not expected by a particular observer, and whether or not an event is considered a black swan depends on individual knowledge and experience.

Such differences in perception mean that at least some members of a diverse group are likely to identify risks that threaten project success. But their insights will not save the project if they are not effectively communicated.

Horizontal communication disconnects between department and division silos, as well as vertical communication disconnects between senior management, sponsors, and project managers on one hand and project managers and team members on the other, also contribute to the formation of isolated and ineffective clusters of risk perception.

Communication disconnects can be aggravated by attitudes toward risk. (In a previous ASK article, “Sinking the Unsinkable: Lessons for Leadership” [Issue 47, Fall 2012], I discussed some examples of the impacts of communication disconnects.)

Certain attitudes function as communication blockers, increasing the chances risks will be ignored. These include denial (“This cannot happen”), minimization (“You are stirring up a tempest in a teacup”), overconfidence and grandiosity (“We are the best organization in this field, we have the best systems in place”), idealization (“We are installing a new system or hiring a new manager that will solve all our problems”), and transference (“If this happens, department X or another entity is to blame”).

Defense mechanisms, when ingrained in an organization’s culture and endorsed by leaders, are detrimental to teamwork and collaboration among departments. They encourage faulty rationales for decisions and complacency, and can lead to intimidation of those who question management.

In the absence of appropriate channels, good multidisciplinary team management, and a positive conflict culture for articulating concerns, team anxiety will flow through the grapevine, and important differences in risk perceptions will end up being discussed out of management awareness and control—in the cafeteria, by the water cooler, or outside the office.

According to research, grapevine activity accelerates any time there is an ambiguous or uncertain situation and absence of sanctioned, open, and trusted channels for venting concerns, including office politics, hidden agendas, and pressure for results perceived as harmful to project objectives. Employees in any organization receive most of their information from informal networks and from a small number of people whose opinions are highly respected. The strength of the informal network will vary according to factors such as organization and country culture. With the Internet, interactions among people sharing and exchanging information in informal virtual communities and networks are accelerating, jumping over organizational, national, and geographical boundaries.

Mapping Risk-Perception Gaps

Recognizing, discussing, and addressing risk-perception gaps are critical to project success, reducing the chances of project-risk blind spots.

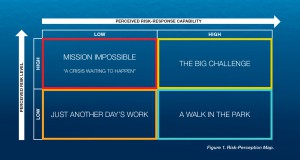

To address this need and complement and leverage other risk management information-gathering techniques and processes, I developed a tool for mapping and easily visualizing risk-perception gaps. The Risk-Perception Map (RPM) charts “perceived risk level” and “perceived risk-response capability” in a 2-by-2 matrix.

Perceived risk level represents an individual’s subjective assessment of risk level absent any action to alter the likelihood or impact of the risk. The perceived risk-response capability is an individual’s subjective assessment of her organization’s ability (using technology, processes, and people) to effectively formulate, plan, and execute responses to identified risks.

The two dimensions group risk perceptions into four categories: Mission Impossible or a Crisis Waiting to Happen; The Big Challenge; A Walk in the Park; and Just Another Day’s Work.

Mission Impossible or A Crisis Waiting to Happen: The observer perceives the project as high risk and does not feel the organization has adequate capabilities and controls in place do deal with it effectively.

Say, for example, that the undersea photograph represents a project that involves scuba diving with sharks. If one judges that swimming with sharks is dangerous and believes that the organization does not have adequate scuba-diving training capabilities, depth of knowledge about shark habits, scuba-diving equipment maintenance policies, practices of regularly feeding sharks, and explicit contingency plans in case something goes wrong, he may be inclined to think this to be a Mission Impossible or a Crisis Waiting to Happen project.

The Big Challenge: The project is perceived by the observer as very risky, but the organization is perceived as having the right capabilities in place to effectively face and manage the risks.

A Walk in the Park: The project is perceived as low risk (the observer perceives sharks or this situation as relatively harmless), and the organization is thought to excel in capabilities, policies, and preparedness to effectively deal with this type of project.

Just Another Day’s Work: The observer perceives the project as low risk and does not believe the organization has adequate capabilities and level of preparedness to deal with it. The likelihood of the risks are small and the consequences, if they do happen, will be minor.

Different stakeholders of your project—project team members, auditors, management, quality, finance, compliance, and other units within and outside the organization—are likely to have different risk perceptions, positioned in different quadrants. Multidisciplinary teams consisting of representatives from different departments and professional backgrounds bring different areas of expertise and provide multiple points of view, and potentially reduce risk blind spots. Some key members of your team may judge the project as Mission Impossible or a Crisis Waiting to Happen, while management may consider it a Walk in the Park or Just Another Day’s Work. If these differences in risk perceptions are ignored or not understood and addressed, the project may not only lack necessary support from key stakeholders but also be headed for a predictable project surprise.

Bridging Risk-Perception Gaps

The RPM helps to overcome communication gaps and defense mechanisms by providing a template and a visual tool for structured discussions about risk-perception differences. By making these differences visible, it makes it much harder to ignore or discount them. Evaluating risk-perception differences becomes an explicit part of project work.

By focusing on capturing, showing, and understanding diverging risk views, the RPM complements other risk management information-gathering techniques and processes. It is especially useful when an organization’s existing risk management processes do not provide adequate, sanctioned, open, and trusted channels and processes to capture and address differences in risk perceptions or when teams become biased or so concerned with reaching consensus and converging to a single “risk score” that they fail to evaluate important risk-perception gaps. It can also help reduce the chances of predictable project surprises and increase the chances of project success.