Robonaut and a spacesuit-gloved hand are extended toward each other to show collaboration.

Photo Credit: NASA

By Natalie Henrich

Calling all mentees and mentors for ACES class of 2012-2013.

That was the headline that grabbed my attention and ultimately led to my participation in a formal mentoring program. ACES is an acronym for Advancing Careers and Employee Success. The agency-supported program is designed to help employees achieve their potential, to help NASA meet the challenges of a changing workforce, and to contribute to making NASA a strong learning organization. The headline attracted my attention because I had been looking for a way to gain a greater understanding of NASA as a whole and reach beyond the circle of my day-to-day working network. When I think about where I want to be in five or ten years, I am not sure I still want to be in my current role. I thought a mentoring experience would be a good first step in exploring other areas of interest.

Step One. Apply. This was a simple process of completing an application and getting supervisory approval to participate in the yearlong program.

Step Two. Mentor Match. That was not as straightforward as step one. There were two options: (1) specifically request a mentor or (2) opt for being matched with someone within a pool of available mentors. Not sure which option would be best, I focused on my goals. I wanted my mentor to have experience-based NASA knowledge in a field that aligned more specifically with my academic background in communication and knowledge management. I wanted someone who had an interesting job, who would readily tell stories about the work, and who would be willing to expose me to his professional world and network.

Ed Hoffman talks about his transition into the role of NASA chief knowledge officer.

Photo Credit: NASA/William Hrybyk

That was when I remembered the “From the Academy Director” articles from ASK Magazine by Edward Hoffman, NASA chief knowledge officer (CKO) and former director of the Academy of Program/Project and Engineering Leadership (APPEL). I remember being drawn in by the headings: “I Would Prefer Not,” “Saturdays with Sinatra,” “Don’t Trust Anyone Under Thirty,” “And the Band Played On.” In these brief essays, Ed communicates a pointed lesson while underscoring the important work of NASA … all within a few paragraphs. I remember repeatedly shaking my head in agreement as I read them.

I thought, “Ed meets all my ’would likes’ in a mentor. He has significant experience-based NASA knowledge. He is a gifted storyteller. He has an interesting job that is outside my functional area and professional network.” I realized having Ed agree to be my mentor would be a big reach. He was the CKO of NASA. At the time, he was also the director of APPEL. He worked at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. I worked at Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, as the Scientific and Technical Information manager in the Logistics and Technical Information Division. Maybe even more of an obstacle, Ed had never heard of me and was not listed in the pool of available mentors. What made me think he would even consider mentoring me?

The first thing I did was comb through the application materials to see if the fine print required a mentee and mentor to be located at the same center. I could not find any such requirement. I did find a line that read, “If you need more information, please contact the program manager.” When I asked her if a mentee could be matched with a mentor located at a different center, she responded, “Who do you have in mind?”

I replied with hesitation and a wince, “Dr. Edward Hoffman at Headquarters.”

To my surprise she did not scoff or chuckle, but replied, “I have known Ed for over twenty years. I will give him a call and let you know.” The rest, so to speak, is history. I sent Ed an e-mail describing myself and why I requested him as a mentor. He graciously agreed to the match without so much as a prescreening phone interview.

I later asked him why he was willing to become my mentor. His answer: “You seemed genuine in your interest, smart about the work, and passionate about your motivations. That is an unbeatable combination, so I felt it was important to support you in your growth and journey.”

Step Three. Partnership Defined. The program kicked off with an orientation session. New mentees were joined by experienced mentors to meet and network—think “speed dating,” but in this case, it was “speed mentoring” to define the roles and responsibilities of both mentors and mentees and outline the organization of the program. My mentoring partnership officially began during a half-day mentoring workshop. Ed traveled to Glenn from Headquarters to participate and to meet me for the first time in person. In one of the first e-mails I received from Ed, he wrote, “There are many things going on across the agency in terms of knowledge, so I will look to give you the opportunity to take part. I’ll start making a list of areas of potential interest for you and importance to NASA.”

Our formal action plan identified agreed-upon developmental experiences that would be of the greatest benefit to me. The mentoring agreement clarified the goals for learning, determined the structure for meetings, and established norms for the partnership. The program also specified individual assessments and evaluations at various checkpoints to allow for proactive adjustments, if needed. These tools not only provided a road map for keeping the mentee–mentor partnership on track, they also defined expectations for both of us.

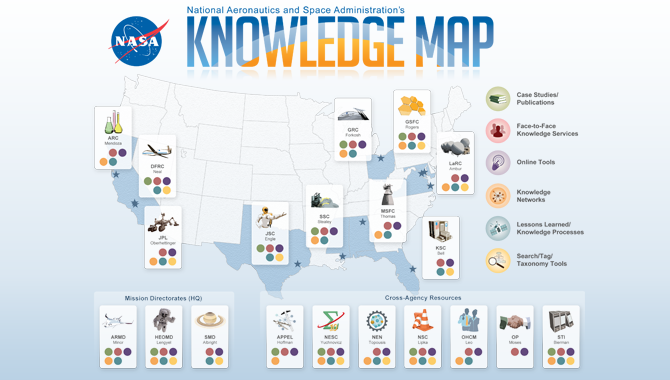

Step Four. The Experience. Ed introduced me to individuals in his professional network, included me in agency knowledge working groups and activities, invited me to the annual NASA Knowledge Community Forum at Kennedy Space Center, and introduced me to knowledge management scholars. He provided me not only with a peek through the window of his professional world, but also access to people and projects that I would have not otherwise been exposed to or known about. For example, in an e-mail sent to some of his colleagues, he wrote, “I want to introduce you to Natalie Henrich, who I am mentoring. Natalie is from Glenn and works Scientific and Technical Information activities, among other assignments. She will be involved in our knowledge work and I want you to know her.”

When I was asked to write this article for ASK Magazine, the editors urged me to be honest and paint an accurate picture of my mentoring experience, including Ed’s accessibility (or lack thereof). At that moment, I remember thinking that people enter mentoring relationships for different reasons. Some may want to gain experience outside their immediate working groups; senior professionals close to retirement may pair with junior employees to pass on knowledge; some may want to learn particular new skills from experts with unique expertise. There are many reasons to seek out a mentoring partnership. In my case, I wanted to hear the stories of an experienced NASA employee and be exposed to a new field. My goal was to watch and learn. In truth, my expectations were in check from the moment I requested Ed as a mentor.

I knew we were geographically separated, so weekly meetings or casual run-ins would not be part of the experience. I figured he was extremely busy and likely traveled a great deal, so there would probably be times when he would not be immediately available. All that was okay with me. In reality, I found Ed to be accessible via phone and e-mail. He shared great stories with me about his experiences at NASA over the years. He not only allowed me to “watch and learn,” but encouraged me to “ask and participate.” On more than one occasion, he prompted me to ask questions and let him know if I wanted to participate in an activity he was involved with or working on. My expectations were not only met, but exceeded.

Step Five. Lesson Learned. From this mentoring experience, I learned to “reach for it.” NASA is a place where “reaching for it” happens on a daily basis, whether it is reaching to launch a vehicle into space, land a rover on Mars, or become one of the best places to work in the federal government. My “reach” was to connect with Ed Hoffman and do all I could to listen and learn. Ed supported my reach and strengthened it by inviting me into his professional network, encouraging me to participate, and making time to be accessible to answer questions and offer suggestions for navigating the organization.

Step Six. Thanks. I would like to thank Ed for mentoring me this past year; my supervisors, Richard Flaisig and Seth Harbaugh, for supporting my participation in the program; and NASA for supporting employees with professional growth and learning opportunities. Mentoring programs like this one make me optimistic that NASA will continue to develop knowledge, which leads to innovations that help the agency realize its vision: To reach for new heights and reveal the unknown, so that what we do and learn will benefit all humankind.

Related Links

- NASA Chief Knowledge Officer

- APPEL Knowledge Forums