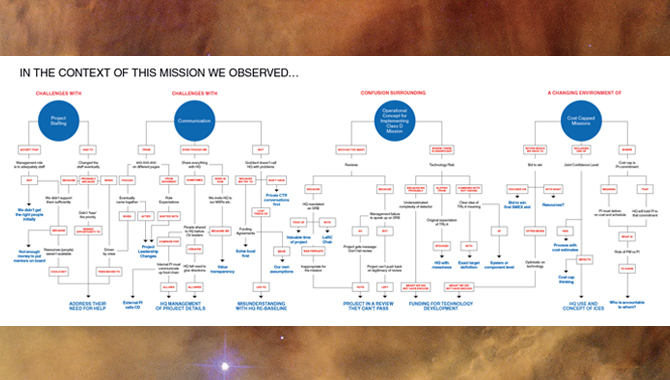

Click here for full resolution version of the above chart.

Image Credit: NASA

The Gravity and Extreme Magnetism SMEX (GEMS) mission failed to pass confirmation in May of 2012.

Among other things, the GEMS mission would have helped determine how spinning black holes affect space-time. The mission had been competitively selected for Phase A Study efforts in May of 2008 and then selected for mission award in June 2009. Along the way, the project got behind and overran its budget. HQ eventually came to believe that it could not be completed on time and within cost and GEMS was cancelled. The story of the mission itself is captured in a case study written at Goddard in the aftermath of processing the lessons learned. What I would like to consider here is how we went about getting lessons from this experience and making sure those lessons were socialized and integrated as widely as possible. I hope that story may help others learn how to get lessons from difficult experiences and reapply them.

The “failure to confirm” decision created a lot of angst at Goddard. Specifically, we struggled to understand how the Center could spend all that effort to win a mission competitively and then fail to execute well enough to keep it going. The Center Director wanted answers and lessons so that something like that would not happen again. He directed me to oversee the process to “make sure we get the real story and understand it.” Initially, the failure led to a lot of finger pointing: within Goddard; between HQ and Goddard; and even at external players. We needed a better approach that would get beyond the blame game and facilitate genuine reflection and learning. The approach I took had four distinct phases:

- Hold Pause and Learn (PaL) sessions to air the issues within the project team.

- Generate concept maps to capture the context of the story.

- Share the maps to generate conversations at both the Center and NASA HQ.

- Develop the story into a case study that could be taught to future groups and used in NASA training.

The PaL with the GEMS project team and the concept maps that emerged from it revealed that there were unresolved issues with how Center management and NASA HQ dealt with the project. This finding suggested we needed to hold a PaL with Goddard senior leaders to elicit their views. Center director Chris Scolese agreed to use an hour of one of his staff meetings to discuss GEMS. That PaL allowed the Center leadership to openly discuss ways in which they had not supported the GEMS team or been as responsive as they needed to be to keep the mission viable.

Fortunately, I had been sent on a detail to SMD at NASA HQ around this time and had good access to the senior leadership within SMD. So we were also able to hold a PaL with leaders at HQ. These three PaLs produced nine concept maps, three from each PaL to capture answers to three basic questions:

- What happened? What did we observe going on?

- What decisions did we make? That is, what was our role?

- What should we do differently? What were the lessons we learned?

The maps in each set were titled Observation, Decisions Made, and Lessons Learned.

The map above, probably not readable on this scale, gives some sense of the patterns of cause and effect these tools reveal. This particular map details the effects of center management decisions regarding staffing, communication, and the operational and budget challenges of a class D mission.

Each group reviewed its own maps but also studied the maps from the other groups. This process helped socialize the different views and make clear what different people saw as significant parts of the story.

I then held a joint session with the project team and Center leadership to gather around the various concept maps and discuss what we should learn from them. These conversations were both therapeutic and instructive. The project team learned that the Center leaders in fact took responsibility for their role in the failure and wanted to learn how to improve. The project team learned things about the way they operated that contributed to the premature end of the GEMS mission. They both learned the point of view of NASA HQ, which was very different from the initial blame talk going on at the Center. The conversation took on the much more productive tone of trying to understand where others were coming from and what we could learn from the experience. Both the project and Goddard leadership wanted to involve NASA HQ as well, so a further joint meeting on GEMS Lessons Learned was held at NASA HQ.

The joint GEMS Lessons Learned Session was held at HQ on November 5, 2013. The room was packed with Goddard Center leadership, HQ SMD leaders, the science PI’s, GEMS project management, and project team personnel. I had gone through all the maps and consolidated the comments into six categories of what I judged to be the major common issues around which lessons needed to be learned. I checked these with key leaders of the project, Goddard and HQ prior to the meeting. I then presented these six broad lessons for discussion to the joint group at NASA HQ. I posted the large concept maps around the room as “evidence” though everyone in the room had already seen them.

The Six Lessons were:

Lesson 1: Recalibrate the Small Explorers Mission (SMEX) Model because it is difficult to use an SMEX, with its tight cost caps, to mentor inexperienced leads. To execute a SMEX now requires very experienced managers who are typically engaged on larger missions. Re-examine the funding profile for practicality rather than just forcing the available funding into a profile that may or may not be executable by the mission.

Lesson 2: Keep the larger science community aware of status and the context of changes. Keep them involved in descopes/replans and recognize that the story ofcompelling science must be retold frequently or it may lose its shine. Keep theProgram office in the loop to HQ and Center management and keep vendors and outside stakeholders up to date on mission status and descopes.

Lesson 3: Clearly define cost cap expectations. Have a kickoff meeting on Independent Cost Estimates between stakeholders (including ICE developer) to establish a joint understanding and clear process. Clearly define the nature of review meetings regarding cost. Clearly specify when the cost cap is being revisited.

Lesson 4: Pay closer attention to staffing, especially during the early phase of mission when it is critical to get ramped up and not fall behind schedule or run over cost. Don’t wait until crisis emerges to address staff needs. Manage key staff changes, being careful to avoid mass (all at once) changes. Take time to establish expectations and understandings.

Lesson 5: Clarify in-house PI mission management. Specify the PI role in communication with HQ and how it relates to the communication roles of project manager and Program Office. Conduct practical PI training at the Center, setting expectations and important role functions.

Lesson 6: Establish a clear process and expectations for Joint Confidence Level and specify how they will figure into HQ Gateway Decisions. Distinguish between the JCL and ICE role for the mission.

As I got up to present the summary charts of the top six lessons we had all agreed on (from the map discussions), I laid down one ground rule: Anyone in the room could suggest actions, but only in regard to their own work. In other words, there would be no sharing of gripes about other organizations couched as lessons learned. All the leaders stepped forward and owned the lessons from GEMS. Each of the key players took their own action items and lessons from the general six presented. Later, I completed the case study and released it for use at Goddard. We use it internally in a leadership training program for people all across the Center. The original project manager comes and shares personal insights to the story. It is now available on the public site of case studies from the GSFC OCKO.

So what happened? Did we learn the lessons? Well, GEMS became a common topic of discussion within SMD and Goddard and shorthand for kinds of mistakes we did not want to repeat. HQ owned up to their actions that had contributed to the outcome as did the Center management. With the burden of “it’s all our fault” removed from the heads of the project team, they also were able to acknowledge missteps and misunderstandings. Once blame and its negative consequences are taken out of the equation, people become able to examine and admit their mistakes. Even the contractor weighed in with their own lessons learned on what they saw and should have done to help mitigate the situation.

In the end, it’s hard to calculate how many people were affected by the lessons of GEMS. What was critical was that many people saw their leaders actively learning lessons right along with them. The blame culture disappeared, accountability increased and the likelihood that a GEMS will be repeated is much lower on all fronts. We still have the case study to remind future project personnel of the lessons so they won’t wear off with time.

Often in these kinds of situations, people are quick to jump to conclusions with the partial information they have. People are also prone to use existing models or allow biases to influence their thinking. Prior experience can actually cloud our thinking, especially when it comes to learning complex lessons. We are creatures of simplification. A simple story (even if untrue or partially true) will remain in circulation long after the facts have been revealed simply because it’s simple and fits some comfortable belief. An important lesson from the GEMS story is that it take effort to get meaningful lessons—lessons that can actually change future behavior.

Ed Rogers is the Chief Knowledge Officer at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.