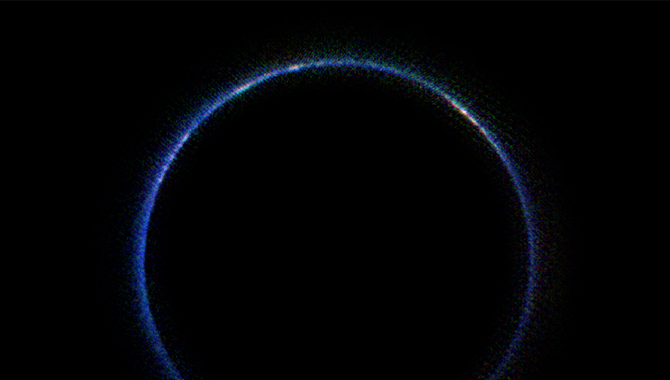

Image taken by the New Horizons spacecraft on July 14, 2015, looking back at Pluto after the flyby. This first look at Pluto’s atmosphere in infrared wavelengths was made with data from the New Horizons Ralph/Linear Etalon Imaging Spectral Array (LEISA) instrument.

Photo Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

The annual public lecture held during Space Science Week examined a discovery that transformed understanding of our solar system and prioritized a mission to Pluto.

Pluto, then considered the ninth planet, was identified in 1930. Its largest moon was spotted in 1978, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that viable plans to visit the planet began to take shape. Even then, it was hard to justify funds to send a spacecraft to an icy world so far from Earth. But that changed when the first Kuiper Belt object came into view. With it, a new zone of the solar system—and a third class of planets—emerged.

“It was this discovery that rocked the very foundations of planetary science,” said Alan Stern, principal investigator for the New Horizons-Pluto mission. He spoke at a special lecture held during Space Science Week: a joint meeting of the National Academies’ Space Studies Board and Board on Physics and Astronomy, where the standing advisory committees discuss issues and advances in their fields.

“We thought we understood the geography of our solar system. We didn’t. We thought we understood the population of planets in our solar system. And we were wrong,” Stern said.

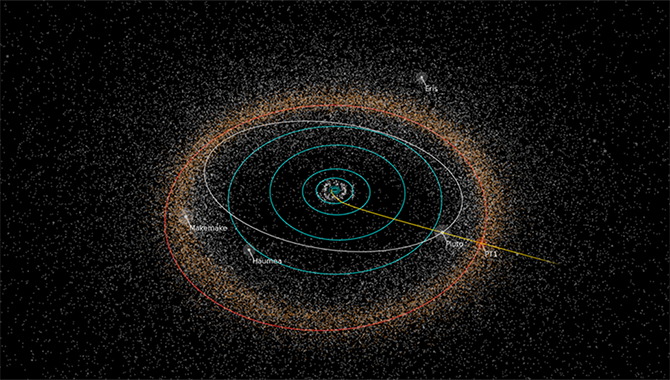

In the outer reaches of the solar system, an area once considered empty space, the Kuiper Belt extends far beyond Neptune. It contains hundreds of thousands of objects that, at more than four and a half billion years old, are believed to be relics of the formation of the solar system. Its discovery had profound consequences not just for planetary science, but for a mission to Pluto as well. Scientists avidly wanted to learn more about Kuiper Belt objects, which could offer novel insight into the development of Earth and other planets. As a result, interest in funding exploration of Pluto skyrocketed.

“[B]y studying Pluto, we could not just learn about the Pluto system and all of its fascinating aspects, but open the exploration of the Kuiper Belt and the small planets of our solar system,” said Stern.

A Pluto mission became the number one priority, for its class, in the next Space Science Decadal Survey. In late 2001, the New Horizons-Pluto mission was selected by NASA. The team was thrilled, but they faced a number of challenges.

The first was how to efficiently travel the vast distance between Earth and Pluto, which varied according to the orbits of the two worlds. To obtain the shortest trajectory, the mission needed to launch between January 11 and January 27, 2006. This would enable them to take advantage of a gravity assist by flying past Jupiter. Any later, and the trip would be extended by years. If they didn’t launch by Valentine’s Day, the launch would have to be postponed until 2007. This gave them four short years to design, build, test, and launch the spacecraft; roughly half the time required by most planetary missions.

A second limitation was financial. The New Horizons budget was five times smaller than Voyager’s, yet the spacecraft had to travel much farther. In addition, to achieve the desired trajectory and make it to Jupiter for the needed gravity assist, New Horizons required several million pounds of thrust at liftoff so it could go faster than any spacecraft ever launched. To achieve this, the team had to purchase a powerful but as-yet-unproven launch vehicle: the three-stage Atlas V.

Fortunately, everything worked essentially as planned. New Horizons left Cape Canaveral during the critical launch window and went supersonic within 30 seconds of liftoff. It passed the moon in nine hours, compared to the three days it took the Apollo missions. It reached Jupiter in 13 months, compared to the four and a half years it took the previous mission to the gas giant. It covered the three billion miles to Pluto in nine and a half years and became the first mission to explore a Kuiper Belt object.

But something unexpected happened in the realm of planetary science shortly after New Horizons left Earth: the International Astronomical Union (IAU) decided that Pluto is not a planet. As increasingly powerful Earth- and space-based observatories identified more and more objects in the Kuiper Belt that rivaled Pluto in size, the IAU revised their definition of a planet. Pluto met two of the new criteria, but not the third: it wasn’t large enough to clear all of the other objects in its orbit. It was relegated to “dwarf planet” status along with many other objects in the belt.

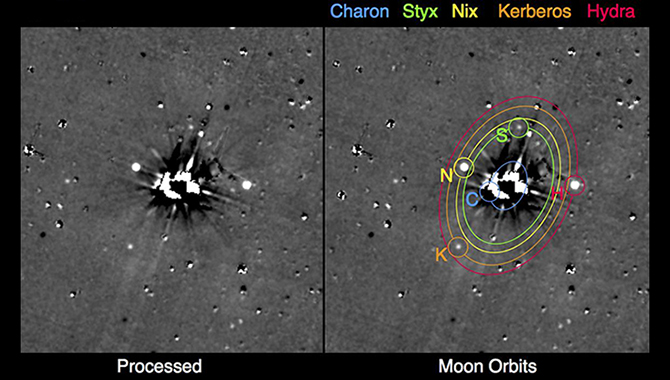

New Horizons, meanwhile, surged forward toward its target. At this point, less than a year after launch, scientists knew the dwarf planet had three moons. Charon, the largest, had been spotted roughly 30 years earlier, while Nix and Hydra were both discovered in 2005. By 2011, another moon was added to the list: Kerberos. And in 2012, a final one was seen: Styx. The New Horizons team had to send their spacecraft past Pluto without coming too close to any of its satellites, including those they had not known about at launch.

On July 14, 2015, they succeeded. New Horizons flew safely through the Pluto system, shutting down all communication with Earth in order to concentrate on capturing scientific data and images. The mission had purchased enormous solid-state drives to store all of their information and invested in a power system that could run up to five instruments at the same time in order to maximize science collection. But budget realities dictated one aspect: at 2,000 bits per second, New Horizons has a relatively slow datalink back to Earth. Following the flyby, its hard drives were filled with data, but it will take until late 2016 to download everything. Each month, the New Horizons team meets to decide what to downlink. They then rely on NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) to receive the information.

“The people that run those [DSN] stations are heroes because they’re our link to the earth,” said Stern. “Every time we want to send a command up to instruct the spacecraft, it’s got to go through them. And every time we want to get data, whether it’s engineering data on the health of the spacecraft or science data, it has to come down through them. And they just do a flawless job. They work in the background, every day, 365 days a year. They’ve been doing it for decades and they’ve made every one of [NASA’s] planetary explorations possible.”

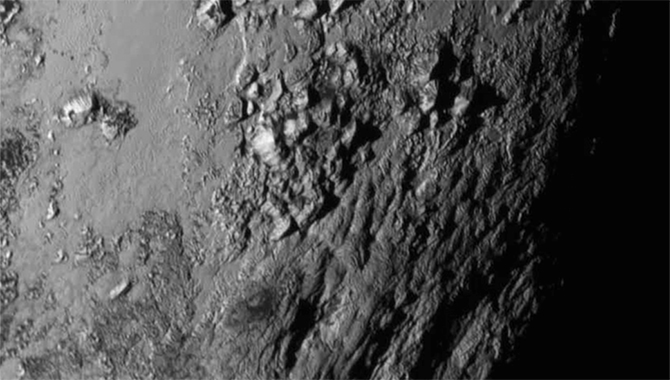

New Horizons is now halfway through the download of their data from the flyby. In the March 18, 2016, edition of the journal Science, the team presented their findings to date. They confirmed some existing beliefs about Pluto: it does have an atmosphere, while Charon, as expected, does not. But the images and data have revealed startling facts as well. For instance, the smooth terrain of Pluto’s “Sputnik Planum” region suggests unexpected geologic activity below its surface. Typically, such activity on an icy world would be due to tidal heating generated by orbiting a large planet, but for Pluto that can’t be the case. It is part of a binary system with Charon in which they orbit each other and, on a much grander scale, the sun. For now, the source of the activity remains a mystery.

The downlink of Pluto flyby data will continue through the end of 2016. At that point, the team is hoping to shift their focus to a new Kuiper Belt object: 2014 MU 69. They have submitted a proposal to NASA for an extended mission. Given its current trajectory, the spacecraft will pass within 3,000 kilometers of MU 69—much closer than the 12,5000 kilometers it was from Pluto at closest approach.

“The spacecraft will be at MU 69 on January 1, 2019,” said Stern. “Let’s just hope that it’s still turned on.”

Whatever it does next, New Horizons has already transformed our understanding of the solar system and our place in it.

“In the lifetime of people in this room, we have explored the entirety of our solar system,” said Stern. “The United States was first to Venus and Mars, and the first to every planet in the solar system. All the way out to Pluto. This country—thanks to…many thousands of engineers and scientists and thanks to NASA—has made a kind of history that will last as long as there is human civilization. Because in that short period of time, from the 1960s to the early 21st century, we opened the solar system to exploration. We did it for all mankind, gave all the data away.”

He added, “And hopefully it’s inspiring people to do great things in the next couple of generations. For example, a journey to Mars with human beings.”

Explore an APPEL case study: Launching New Horizons: The RP-1 Tank Decision.

Read an APPEL News article about the New Horizons flyby of Pluto.

Watch a video about New Horizons and its next potential target, 2014 MU 69.