Harrison H. Schmitt examines a boulder during the Apollo 17 mission. The Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV), which transported Schmitt and Eugene A. Cernan to this site, is seen in the background.

Credit: NASA/Eugene Cernan

Harrison Schmitt, who trained earlier astronauts, examines lunar geology up close in final Apollo mission.

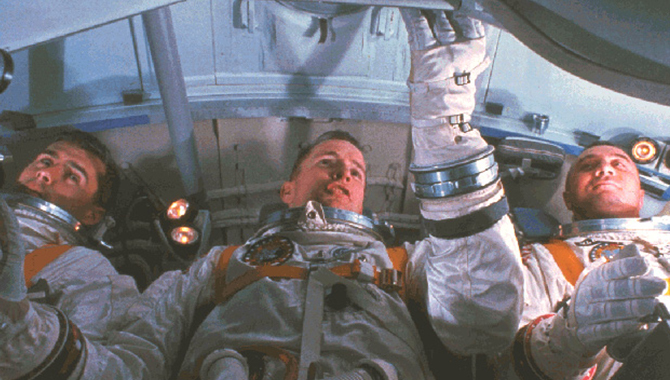

When Commander Eugene A. Cernan, Command Module Pilot Ronald E. Evans, and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison H. Schmitt climbed into the command module of Apollo 17 in December 1972—47 years ago this month—they knew that their mission would be the last of the storied and highly successful Apollo program. Apollo 18, 19, and 20 had already been cancelled.

Although 17 would be the last Apollo flight, the mission was highly ambitious and marked by significant firsts. It was the first night launch during the Apollo program, blasting off at 12:33 a.m. ET on December 7. It was also the first mission to include a scientist-astronaut, Schmitt.

Astronaut Eugene A. Cernan (left) and scientist-astronaut Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt aboard the Apollo 17 spacecraft during the final lunar landing mission in NASA’s Apollo program.

Credit: NASA

It wasn’t, however, Cernan’s first trip to the Moon. The veteran astronaut, who had flown on Gemini 9A, was the lunar module pilot on Apollo 10, a mission that orbited the Moon 31 times as the crew tested the procedures that would be used in Apollo 11, including the lunar module (LM), which Cernan and Commander Thomas P. Stafford flew within 8.4 nautical miles of the surface before returning to the command module. As an accomplished veteran of the space program, Cernan set high goals for his return to the Moon.

“Well, I wanted it to be the best mission ever in Apollo,” Cernan recalled in an oral history. “We had a lot of new things. We were going to be the first night launch. It was going to be the longest stay. It was going to be in a mountainous area. I had the first scientist to fly. I think that was a significant thing—a lunar geologist. I just wanted it to be the best, as we all do. We build on those that went before us.”

In the weeks leading up to the night launch, the astronauts and many of the workers at mission control gradually shifted their sleep schedules to the point that they were waking up and having breakfast in the middle of the afternoon so that they could be at their peak and ready at midnight.

The launch atop the powerful Saturn V rocket was the most dynamically exciting part of the mission, Schmitt recalled in an oral history. “It’s a very heavy vibration. Very slow acceleration at first, but heavy, heavy vibration. You build up, over two minutes and forty-five seconds, about 4 Gs acceleration. At that point everything shuts down. You drop off the first stage and then you ignite the second stage, the S-II, and you’re back on your way, but only at one and a half Gs. So, there’s a big change, it’s from 4 Gs to a minus one and a half, as the whole stack unloads, to a plus one and a half, as you go on … the second stage. And that all happens in just slightly over a second.”

The landing site, known as Taurus-Littrow, is on the edges of Mare Serenitatis. With ancient mountains surrounding a plain of igneous rock from volcanic activity, the site provided NASA the opportunity to gather rock samples from a broad range of time periods during the Moon’s history. Schmitt, who holds a Ph.D. in geology from Harvard, and had trained earlier astronauts in how to assess sites, was able to use his expertise to full advantage here.

Astronaut Eugene A. Cernan, commander, makes a short checkout of the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) during the early part of the first Apollo 17 extravehicular activity (EVA) at the Taurus-Littrow landing site.

Credit: NASA

It wasn’t until Schmitt had moved away from the lunar module to take a series of panoramic images early in the mission that he began to comprehend the full majesty of the site. “That’s the first time I had a chance to see this magnificent valley that we were in—a valley deeper than the Grand Canyon… Six to 7,000-foot mountains on either side, 35 miles long, and about four miles wide where we had landed. The slopes of the valley walls were brilliantly illuminated by this little sun… The sun itself was brighter than any sun that I had ever seen, of course, in New Mexico or anywhere else, in a desert-like landscape,” Schmitt said.

“But most hard, I think, to get used to was a black sky, an absolutely black sky,” said Schmitt, adding that photographs don’t capture the full contrast the astronauts experienced between the black sky and the surface of the Moon.

Schmitt found that the principles of integrating your eyes and your hands and your mind to process a geology site on the Earth were as equally effective for exploration on the Moon. Extensive training before the mission somewhat mitigated the foreign nature of the environment. But the bulky nature of the space suit, especially the gloves, hampered geologic exploration.

Apollo 17 included a Lunar Rover Vehicle, which the astronauts drove a total of about 22 miles, traveling as far as 4.7 miles away from the LM. The astronauts spent about 75 hours on the Moon, with an impressive 22 hours of that spent out of the capsule, working on the lunar surface. The astronauts returned 243 pounds of rocks and regolith, some of which is still being studied today, including rare orange volcanic material formed about 3.5 billion years ago.

The LM lifted off the surface of the Moon late on December 14 and splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on December 19. The astronauts were recovered by the USS Ticonderoga.

“I’m the luckiest human being in the world,” Cernan would recall years later. “Got to walk in space, got to go to the Moon twice, got to walk on the Moon, got to command my own crew. I’m not sure what else a human being can ask for.”