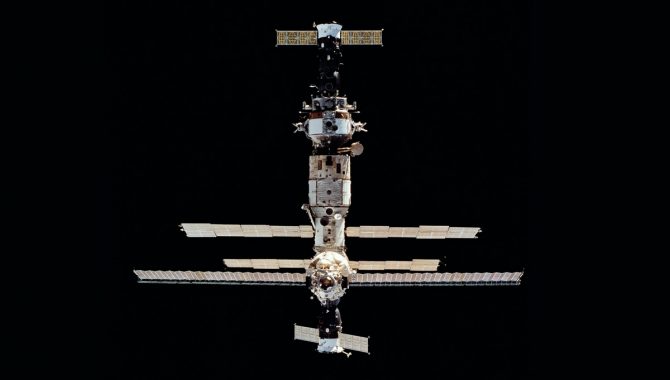

The Russian space station Mir as Space Shuttle Discovery pulls closer for the first rendezvous in a program that would eventually include nine docking missions.

Credit: NASA/JSC

Mission improved communications and set stage for docking missions to come.

On February 6, 1995, 26 years ago this month, the crew of STS-63 looked through the windows of Space Shuttle Discovery at a remarkable sight. The Russian space station Mir was shining brightly before them against the darkness of space. After months of negotiations and careful maneuvering, the shuttle was now just 37 feet away and the crew could clearly see Commander Alexander Viktorenko, Flight Engineer Yelena Kondakova, and physician Valery Polyakov waving from Mir’s windows.

“You know, approaching the vehicle, you’re so focused on doing the technical, the test pilot things, evaluating the systems and the handling qualities, but you are just blown away by the sight that you’re seeing of that huge, giant space station out the window,” recalled STS-63 Commander James D. Wetherbee, a veteran astronaut on his third shuttle mission, the second as Commander. “Ever since I was ten years old and wanted to be an astronaut, I’ve been watching these science fiction movies of these spaceships that come up next to a big, giant space station, and all of those thoughts came back to me, you know.”

Astronaut Eileen M. Collins at the pilot’s station during “hotfiring” procedure to clear leaking thruster prior to rendezvous with Russia’s Mir Space Station.

Credit: NASA/JSC

The pilot of STS-63 was Eileen M. Collins, the first female to pilot the space shuttle who flew like a veteran on this, her rookie flight, Wetherbee recalled. The eight-and-a-half-minute ride into orbit on February 3, 1995 went smoothly, but once the large external fuel tank separated, the crew received warnings that one of the 44 orbiter Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters—crucial for maneuvering in orbit—was leaking and two others were not operating.

“…You could look out the back window and you could see the propellant going up for miles,” Wetherbee recalled in an oral history. “It kind of goes in a cone-shaped pattern, because there’s no atmosphere to attenuate its motion, and it just goes up pretty straight and it just continues, like a snowstorm for five miles up into space. … I was pretty much convinced that we were not going to be able to rendezvous with Mir, and it was pretty disappointing.”

Although STS-63 was not going to dock with Mir, the rendezvous and close approach was important to test the sensors that were providing Discovery’s computer with information about its position relative to Mir for a future mission that would dock, STS-71. The leak prompted extensive negotiations and technical cooperation between the U.S. and Russian space teams. Eventually, with a thruster manifold closed and the leak reduced, a decision was reached to move forward with the rendezvous using a backup thruster.

“It actually was fortuitous that we had the leak, because it forced people to communicate and talk with each other,” Wetherbee said. “…We got people talking to each other, the engineers on the ground discussing the leak. Opening up their books and sharing data with each other did a lot to help STS-71, the first docking mission, because then they all were friends, and it went along more smoothly.”

The Mission Specialists on STS-63 were Bernard A. Harris, Jr., Michael Foale, Janice E. Voss, and Russian Cosmonaut Vladimir G. Titov, who had once shared the record for longest individual spaceflight, having spent 365 days living in Mir.

It was Titov’s idea for the crew of STS-63 to reach out before launch and speak with the crew on Mir. Titov had a direct number to reach the Russian space station and on his second attempt dialing from a landline at Kennedy Space Center, the call went through.

“…We were sitting around in an office down in Florida, getting ready to launch, talking to the [Mir] crew members, flying overhead. So, we were able to develop a little bit of a friendship, even though it was by telephone and you couldn’t see them,” Wetherbee recalled.

“So then when we saw them in person, across …[the] cold, dark void of space, waving to them, it was like we were crewmates, even though we weren’t on the same vehicle, so it really was a good feeling.”

Wearing red shirts are Payload Commander and Mission Specialist Bernard Harris Jr. and Mission Specialist Michael Foale. Wearing blue shirts are Mission Specialist Janice Voss and Commander James Wetherbee. Wearing white shirts are Mission Specialist Vladimir Titov and Pilot Collins.

Credit: NASA

Wetherbee, who was well aware of the significance of the rendezvous to both the U.S. and Russia, developed special remarks to deliver in both English and Russian after the shuttle had reached its closest point to Mir. As he spoke, the crew managed the technical aspects of the flight to make sure gravitational attraction didn’t draw the shuttle closer than was allowed.

“As we are bringing our spaceships closer together, we are bringing our nations closer together,” Wetherbee said from space. “The next time we approach, we will shake your hand and together we will lead our world into the next millennium.”

Discovery’s payload bay was filled with research objectives to keep the crew busy before and after the Mir rendezvous, including SPACEHAB-3, a commercial module in the forward payload bay that contained 20 experiments focusing on biotechnology, advanced materials research, technology demonstrations, and measurements of on-orbit accelerations.

But it’s the rendezvous with Mir for which STS-63 is primarily remembered, building on the success of the Apollo-Soyuz mission 20 years earlier and opening the door for nine shuttle docking missions to come. STS-63 returned to Earth on February 11, 1995. Wetherbee served as Commander on three more shuttle flights, returning to Mir with STS-86, this time to dock. Collins became NASA’s first female shuttle Commander with STS-93, deploying the Chandra X-Ray Observatory. She also commanded STS-114.

To learn more about STS-63 and all 135 space shuttle missions, please visit APPEL Knowledge Services’ new Shuttle Era Resources page.