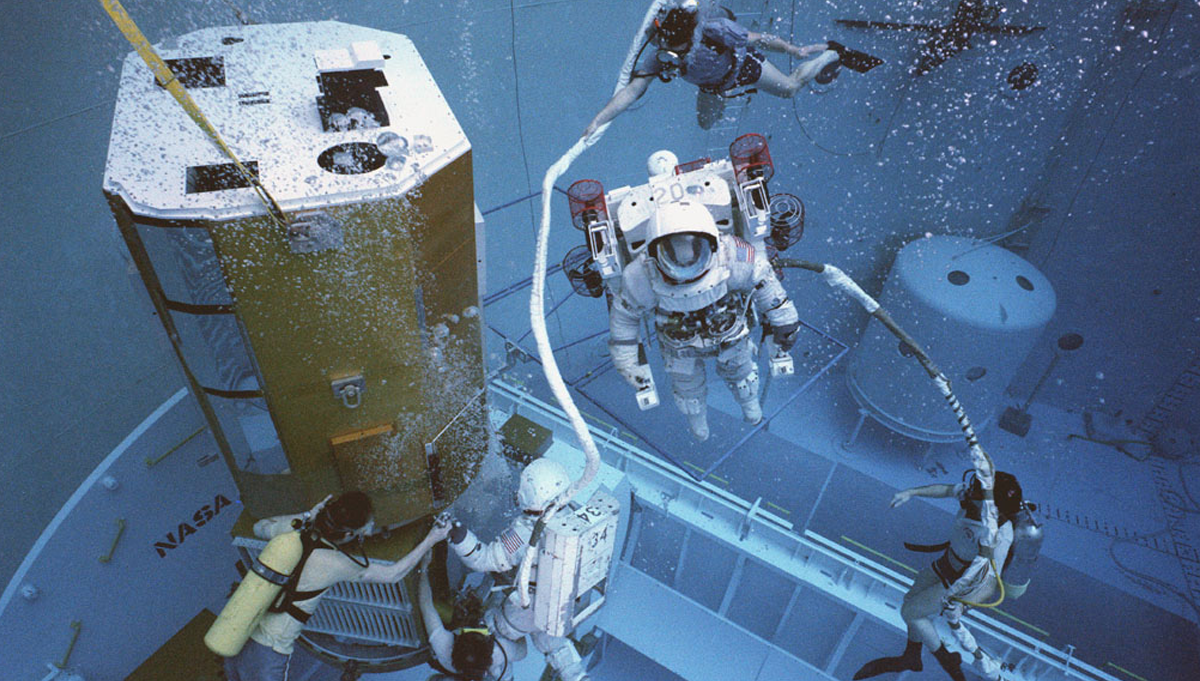

Thirteen tons of telescopes and support equipment occupy the payload bay of the Space Shuttle Columbia for mission STS-35, the first shuttle mission dedicated entirely to astronomy.

Credit: NASA

STS-35 was the first mission devoted exclusively to astronomy.

Just after midnight on December 2, 1990, Commander Vance D. Brand, Pilot Guy S. Gardner and the crew of STS-35 were strapped into Space Shuttle Columbia on Launchpad 39B, Kennedy Space Center. After about six and a half months of delays, Brand watched the Moon move across the night sky as the countdown moved toward a 1:49 a.m. launch.

The Astro Observatory is backdropped against the blue and white of Earth in this 35mm scene photographed through Columbia’s aft flight deck windows.

Credit: NASA

When Columbia’s main engines and solid rocket boosters ignited, Brand recalled having the feeling that they were lighting up the night sky all over Florida’s space coast. “It was … like night flying in an airplane. You had to really have your lights adjusted … [and] pay attention to your gauges. … You couldn’t really tell much about what was going on outside. You couldn’t see the horizon very well,” Brand recalled in an oral history.

Columbia carried the Spacelab pallet fitted with an installation of four telescopes collectively known as the Astro Observatory. Known as Astro-1, it was the first shuttle mission devoted exclusively to astronomy. These telescopes observed, from space, the faint emissions in the ultraviolet and X-ray portions of the spectrum that are difficult to observe from Earth because they are largely absorbed by the atmosphere. Researchers wanted to find evidence of violent, high-energy phenomena from distant stars and galaxies.

“We had about thirteen tons [of] telescopes in the back of the Shuttle, and they were not to be deployed. They were to be taken up, used for eight or nine days, and brought back,” Brand recalled. “It was another use of the Shuttle. People used to say [the Space Shuttle is like] a truck or it’s a platform, and it can be used for many different things. So, it was important to engage with the scientists.”

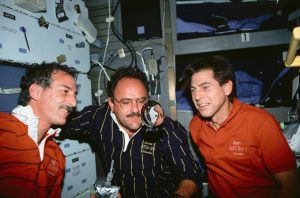

Four members of the crew held doctorate degrees in astronomy or related fields: Payload Specialists Samuel T. Durrance and Ronald A. Parise, and Mission Specialists Robert A. Parker and Jeffrey A. Hoffman, both NASA astronauts. Brand, Gardner, and Mission Specialist John. M. Lounge focused on shuttle operations.

“These guys were … all very intelligent, capable guys, and they did a great job. When we flew, everybody was really up to speed on the objects that had to be viewed, [the] astronomical objects, which were largely hot spots in the universe, places where cataclysmic events had occurred … [such as an] exploding star. So, it was very interesting,” Brand recalled.

STS-35 crewmembers perform a microgravity experiment using their drinking water. Pictured: Mission Specialist (MS) Jeffrey A. Hoffman (left), MS John M. Lounge (center) and Payload Specialist Samuel T. Durrance.

Credit: NASA

The crew would be tested on orbit when anomalies with the mount that held and pointed the ultraviolet telescopes presented a major challenge.

“[The mount] had been tested … on the ground thoroughly, but there are things about being in space that couldn’t be [duplicated in] the ground [tests]. … For example, the mount itself is rather weak [structurally], and you can’t [do an end-to end test] on the ground [with] it pointing at … stars, because it’s not strong enough. [On orbit in] weightlessness, … it’s plenty strong enough to do its job. … [On orbit] we found out that there were some things about the automatic pointing system that didn’t work right,” Brand recalled.

Unable to point the ultraviolet telescopes, the crew on orbit worked with teams at Johnson Space Center and Marshall Space Flight Center to develop a workaround that saved the mission, Brand said. It took about a day to develop the contingency plan for pointing the telescope in which Brand would first rotate the spacecraft to an attitude and then one of the four astronomers onboard would manually point the ultraviolet telescopes, which were then fine-tuned by teams on the ground. The anomalies meant that the crew completed about 67 percent of the stated mission goals of Astro-1, making 231 observations of 130 targets.

Astro-1 gathered valuable data, providing unprecedented insight into Universe via the ultraviolet spectrum. The Astro Observatory flew a second time—Astro-2—aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour, launching on March 2, 1995. The research teams from Astro-2 produced 150 technical papers from that data, including the first measurements of the diffuse intergalactic medium posited in the Big Bang theory.

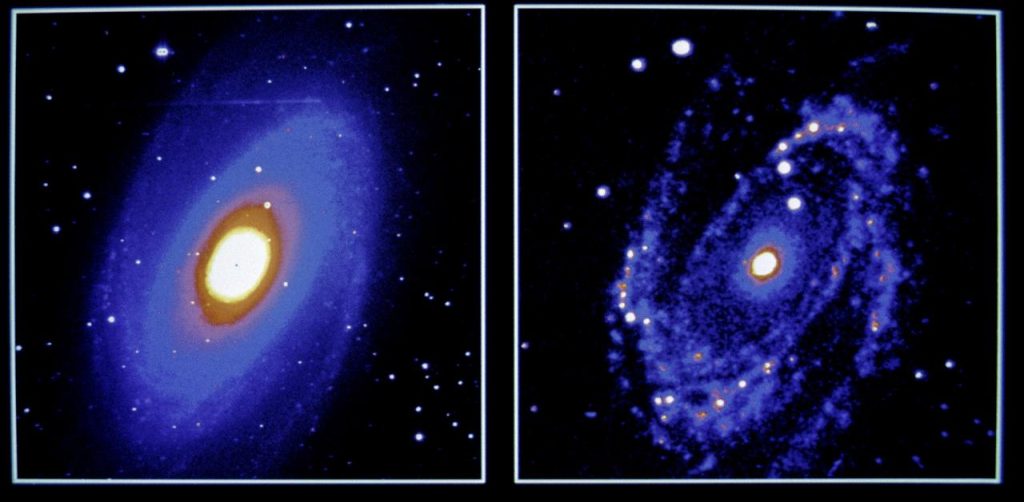

The Spiral Galaxy M81, about 12-million light years from Earth, photographed by the Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (UIT) during Astro-1 (left) and in red light by a 36-inch (0.9-meter) telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory near Tucson, Arizona.

Credit: NASA

The STS-35 mission was reduced by a day to return ahead of forecast bad weather at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. Brand’s fourth and final spaceflight ended with a night landing, just short of 10 p.m. PST. Brand had to compensate for the 13 tons of telescopes returning in Columbia’s payload bay and a strong tail wind.

Brand went on to become the Assistant Director for Flight Operations and Deputy Director for Aerospace Projects at the Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Gardner served as Commandant of the USAF Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California and later Program Director of the joint U.S. and Russian Shuttle-Mir Program.

Visit APPEL KS’s Shuttle Era Resources Page to learn more about STS-35 and the 134 other shuttle missions, missions that deployed key satellites, repaired the Hubble Space Telescope, enabled important new research, and were instrumental in construction of the International Space Station. The Shuttle Era Resources Page also contains important resources on the Challenger and Columbia tragedies and enduring lessons learned.