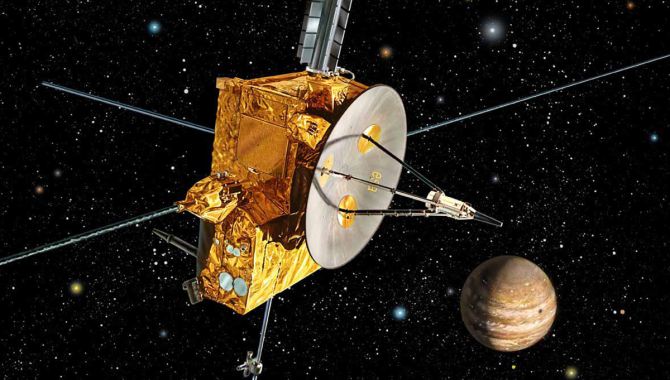

An artist impression of Ulysses spacecraft at Jupiter. Ulysses used Jupiter's powerful gravity to hurl it out of the Plane of the Ecliptic so it could study the polar regions of the Sun.

Credit: ESA/NASA/JPL-Caltech

Crew of STS-41 launches spacecraft on out-of-ecliptic mission to the Sun.

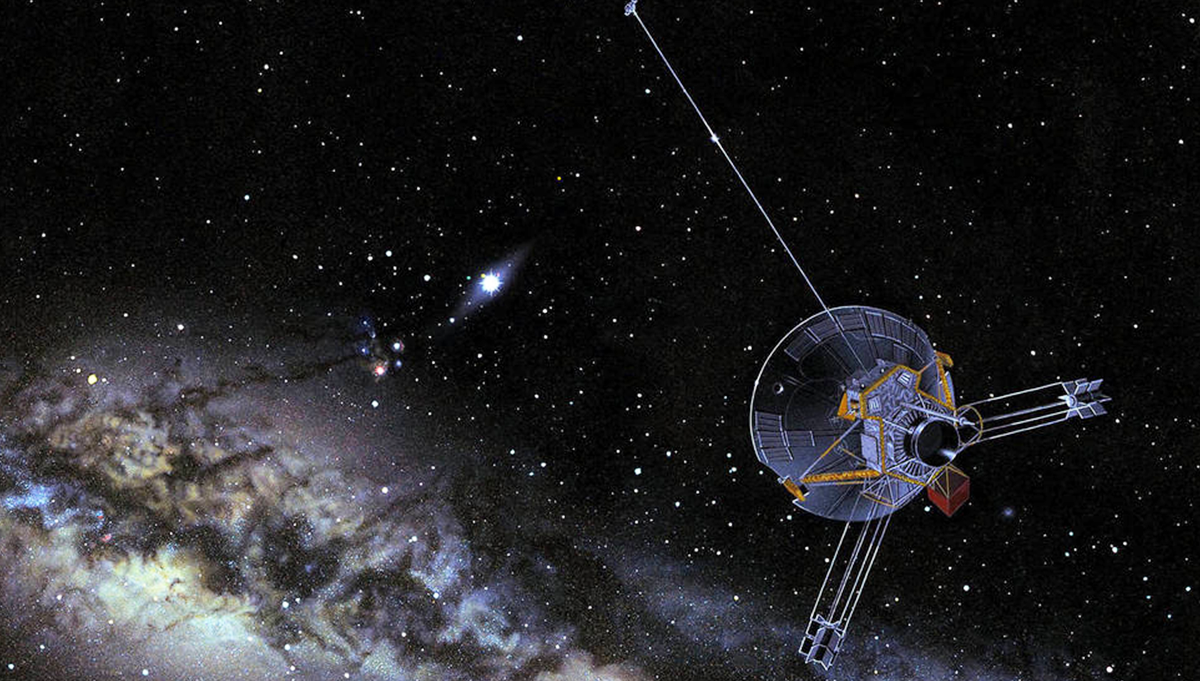

In the early 1970s, NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) began planning a mission that would send two spacecrafts through Jupiter’s gravitational field and on to the Sun, where they would pass over the north and south poles, mapping previously unstudied regions of the Sun and gathering vital data about solar wind, plasma, and the Sun’s magnetic field.

The mission would require what is known as an “out-of-ecliptic” orbit, meaning that a spacecraft would operate outside the ecliptic plane in which most major bodies orbit the Sun. Scientists began studying out-of-ecliptic missions at the dawn of the space age, but it took decades to develop the technology to navigate the vast distances required and effectively utilize gravity assists.

By the mid-1970s, however, buoyed by the success of NASA’s Pioneer 10 and 11 at Jupiter, there was growing consensus in the scientific community that such a mission could lead to a vast expansion of human understanding about the Sun and the resulting effects it has on Earth’s electromagnetic and meteorological conditions.

The Ulysses spacecraft undergoes testing at the vacuum spin-balancing facility at the European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands.

Credit: NASA/JSC

As planning progressed, the mission was pared to a single spacecraft, provided by ESA and built by Dornier Systems in Germany. NASA provided the radioisotope thermoelectric generator that powered the spacecraft and launch services, including the inertial upper stage and payload-assist module that put the spacecraft on a course for Jupiter. The spacecraft was named Ulysses, an allusion to the protagonist of the Odyssey, who travelled great distances and explored uncharted territory.

Ulysses was at Kennedy Space Center awaiting a May 1986 launch, but it was dismantled and returned to Europe after the Challenger disaster in January 1986. Following the investigation and changes to the shuttle program, it was slated to launch on October 6, 1990, aboard STS-41.

“Well, that was one of our first things, to go over to Europe and meet the European Space Agency people that were building the Ulysses spacecraft,” recalled Richard N. Richards, commander of STS-41, in an oral history. “So, we did that, and they were a great bunch. …[Ulysses] was a small thing. … You could literally go out there and pick it up and put it in the back of your pickup truck and drive off with it if you wanted to,” he said, were it not for the weight of the nuclear power source.

STS-41 was Richards’ second spaceflight. Robert D. Cabana was the pilot. “It was going to be his first flight. …I’d just gone through that, so I was interested to try to make Bob as comfortable as possible. … We had a crew of five. Two of the mission specialists, Bruce [E.] Melnick and Tom [Thomas D.] Akers had never flown before. And the only other seasoned guy I had—he had only flown one flight—was Bill [William M.] Shepherd. So, Bill and I …, with our one great one-flight experience, were the veterans. And the rest of us were rookies. … I was struck by how new this particular crew was,” Richards recalled.

STS-41 launched aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery at 7:47 a.m. on October 6, 1990. Early that afternoon, the crew opened the Payload Bay doors and began the complex process that released Ulysses to begin its unprecedented, nearly 19-year voyage to the Sun via Jupiter. Akers was key to the process, operating a series of switches in sequence on a flight deck panel to prepare Ulysses.

A 35mm preset camera on Discovery’s middeck captures the traditional in-space portrait of the STS-41 crewmembers. In front are (l.-r.) Astronauts Richard N. Richards, mission commander; and Robert D. Cabana, pilot. In the rear are (l.-r.) Astronauts Thomas D. Akers, Bruce E. Melnick and William M. Shepherd.

Credit: NASA

“Never forget Tom Akers, quite a guy,” Richards recalled. “…We were counting down, and once you start this process, it’s an automatic process and you have to get it done. We were at like T-minus deploy, minus maybe four or five minutes, and Tom was down there doing his thing…. And so, [for] four minutes, I had not bothered Tom, not asked him one thing the entire sequence, and he’d thrown all these switches, configured the vehicle. … A couple times in the simulations, he had been late, and so we just said, ‘Tom, you know that’s a big deal.’ ”

“So, finally, about four minutes, I’ll never forget, I had to ask him, said, ‘Tom, how you doing?’ And he just turned to me, and he looked up at me, and smiled and said, ‘Never had so much time,’” Richards recalled with a laugh. “And I relaxed, and everybody relaxed and so we said, ‘Okay, we’re okay.’ And the spacecraft came out, came out beautifully…”

Ulysses, equipped with a suite of precision instruments to gather data at the Sun as never before, arrived at Jupiter in February 1992. It passed over the Sun’s south pole first, in 1994. In 1995, it passed over the Sun’s north pole. Ulysses then headed back to Jupiter to begin its second, six-year, out-of-ecliptic orbit around the Sun.

Over a journey that ultimately covered 5.4 billion miles, Ulysses contributed to key discoveries about the Sun, including the presence of an interstellar cloud of dust and gas, the composition of cosmic-ray particles, and revealed that the magnetic field emanating from the sun’s poles during the mission was much weaker than expected.

“Over almost two decades of science observations by Ulysses, we have learned a lot more than we expected about our star and the way it interacts with the space surrounding it,” said Richard Marsden, Ulysses project scientist and mission manager for the European Space Agency (ESA), in a NASA press release in 2008. “Solar missions have appeared in recent years, but Ulysses is still unique today. Its special point of view over the sun’s poles never has been covered by any other mission.”

Building on the legacy of Ulysses and previous solar missions, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe is making a series of 24, ever-closer orbits around the Sun. It became the first spacecraft to enter the Sun’s atmosphere on April 28, 2021, during its eighth flyby. It will pass within 3.83 million miles of the solar surface in 2025. Another spacecraft currently orbiting the Sun is the Solar Orbiter, a joint mission of NASA and ESA. Using gravity assists from Venus and Earth, the Solar Orbiter will eventually travel well outside the ecliptic plane and capture the first images of the Sun’s poles taken from high latitudes.

Visit APPEL KS’s Shuttle Era Resources Page to learn more about STS-41 and the other 134 shuttle missions over 30 years, missions that deployed key satellites, repaired the Hubble Space Telescope, enabled important new research, and were instrumental in construction of the International Space Station. The Shuttle Era Resources Page also contains important resources on the Challenger and Columbia accidents and enduring lessons learned.