Apollo 8 astronauts Frank Borman, commander (left); William Anders, Lunar Module Pilot (right); and James Lovell, Command Module Pilot (center) safely returned to Earth on December 27, 1968, after successfully orbiting the Moon on the second crewed Apollo mission.

Photo Credit: NASA

Apollo 8 spaceflight to the Moon was a gamechanger.

On a Friday in August 1968, Christopher Kraft, Director of Flight Operations at NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), called Flight Director Eugene F. Kranz to his office in Houston. At a time when no astronaut had yet flown on an Apollo mission, leaders of the program were considering one of the boldest decisions in NASA’s history. Kraft was holding a series of fact-finding meetings. He asked Kranz to come back Saturday morning with any reasons NASA shouldn’t fly to the Moon in December.

“Well, this is in August, so we’re talking in four months we’re going to go to the Moon. And this sort of catches everybody by surprise here,” Kranz recalled in an oral history. “Obviously you can pull together a list of reasons you can’t do things as long as your arm, but that wasn’t the way you did things in those days. What you really did is say, ‘Why can’t we?’ So, you kept looking for the opportunities that were there.”

The USS Yorktown hoists the Apollo 8 capsule aboard after its successfully splashdown in 1968, the end of the first human mission to the Moon. Photo Credit: NASA

Kraft had a great deal of confidence that the Apollo Command/Service Module was ready to fly the more than 230,000 miles to the Moon. Following the Apollo 1 fire, George Low had been appointed as the manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office, instituting the Apollo Spacecraft Configuration Control Board, which debated and decided every engineering change to the capsule, including nearly 1,500 in the aftermath of the accident investigation. Changes were communicated widely so that every engineer and technician who touched the capsule was aware of them. Kraft oversaw a similar board monitoring development of Apollo’s computer control systems and software.

“The Command/Service Module had become a good-looking piece of hardware. The Lunar Module had just been delivered to the Cape. It was a mess. Now, it was a mess because we were using these very delicate pieces of structure because we had to. It had to be light. The wiring had to be light. It had to have very small and probably inadequate insulation. It was fragile. When they got it to the Cape, they just had a time getting it checked out. Just everything was going wrong with it,” Kraft recalled in an oral history.

One of the main objectives of a December mission had been to test the Lunar Module in Earth orbit. Without that option, NASA began looking for ways to maintain the December launch while advancing the program’s goals. In hindsight, it can be difficult to appreciate how confident the decision to go to the Moon was. All the Apollo missions to this point were uncrewed test flights.

Apollo 4 launched in November 1967, the successful first flight of the massive Saturn V rocket. After Apollo 5 launched atop a Saturn IB in January 1968, the Saturn V was tested again in April with Apollo 6.

Pictured (left to right) are Apollo 8 crew members Frank Borman, commander; James Lovell, Command Module (CM) pilot; and William Anders, Lunar Module (LM) pilot, having breakfast on the day of launch.

Photo Credit: NASA

“We flew the second flight, and it was a disaster. I want to emphasize that. It was a disaster,” Kraft said, noting the first stage had significant pogo oscillations, a type of self-excited vibration caused by combustion instability. “The second stage had pogo so badly that it shook a 12-inch I-beam, it deflected that thing a foot. The third stage ignited and then shut down, and it would not restart, which was a requirement to go to the Moon. It had some vibratory problems associated with it also,” Kraft said.

Following Apollo 6, more than 1,000 engineers went to work on the problem, led by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The solution they developed included further “de-tuning” the powerful engines of the rocket’s first stage to change the vibrational frequency and using helium gas to fill cavities on the liquid oxygen supply lines, which would act as shock absorbers. Mathematical models and static fire testing validated the solution in July.

Kranz left the August meeting and began quietly assembling a team to consider the question of a Moon mission in a little more than two months after Apollo 7, which was scheduled to be the first crewed mission of the program, launching in October atop a Saturn IB.

“We were really told to keep this thing sort of in secret. In fact, we did a lot of these things in those days. You’d try to keep something going, but it was like trying to hide an elephant in your garage,” Kranz recalled.

One of the people enlisted was Bob Ernull, a computer expert whom Kraft tasked at a Saturday morning meeting with developing an initial mission plan, complete with launch windows and landing zones. “Chris, if you’ll give me every computer in Building 12 and in Building 30 for the entire weekend, I will give you the answer on Monday,” Ernull replied.

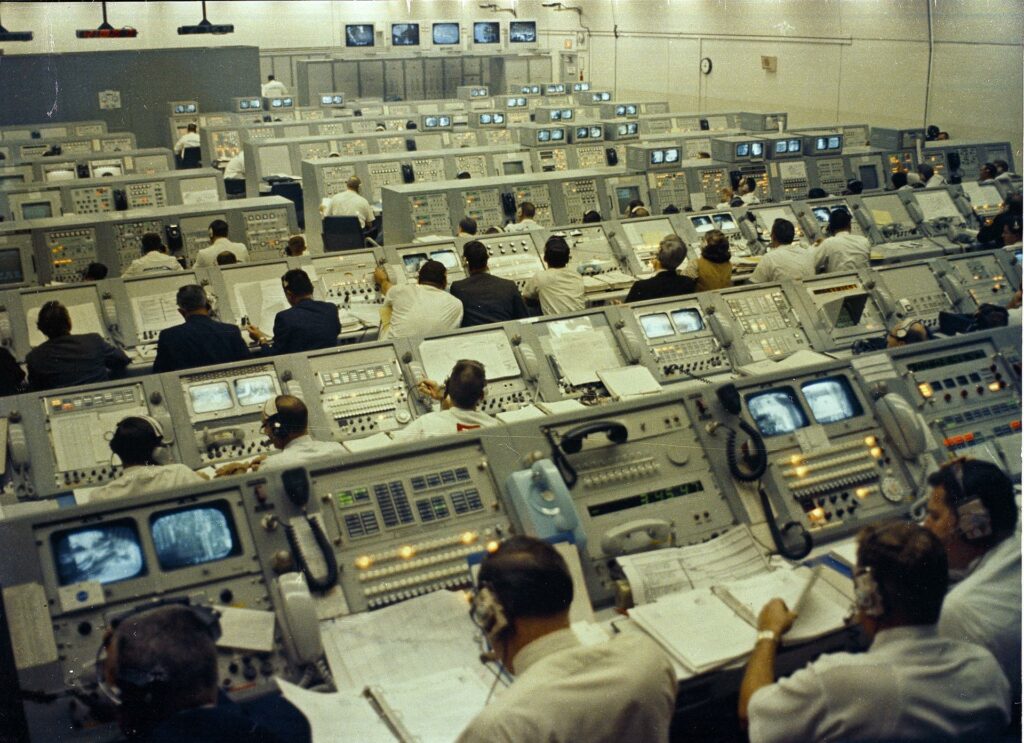

The Launch Control Center at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center was filled with activity as the Apollo 8 astronauts began their journey to the Moon. Photo Credit: NASA

Ernull’s calculations produced a set of three spaceflight windows in December. Two would splash down in the Atlantic Ocean, the third in the Pacific. NASA selected the window with the Pacific splashdown, launching on December 21, orbiting the Moon on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, and returning on December 27.

“I thought it was great,” said George E. Mueller, Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, in an oral history. “But I wanted to make sure that we did this thorough review, and so I used it as … a lever to get that kind of a review, which really found a few things and straightened them out before we were satisfied that it was safe to go.”

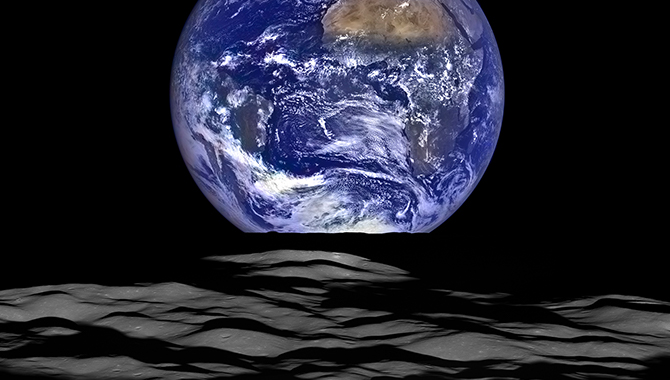

Fifty-five years ago this month, Apollo 8 fascinated the world. Nearly 1 billion people are estimated to have followed news of the mission. NASA veteran Frank Borman was the flight’s Commander, James A. Lovell Jr. was the Command Module Pilot, and William A. Anders was the Lunar Module Pilot. The mission included several live television broadcasts, including one while the capsule was orbiting within 70 miles of the lunar surface. During the mission, Anders captured the iconic Earthrise image.

“Man had been looking at the Moon ever since they could see and wondering about it. … Apollo 8 probably remains as the most significant mission ever flown,” Kraft recalled. “It was an opportunity for those of us who were allowed to do it that doesn’t present itself very often in any human being’s life. We were extremely fortunate that all the conjunction of the stars and the politics and the money and the technology all came together in [1968].”