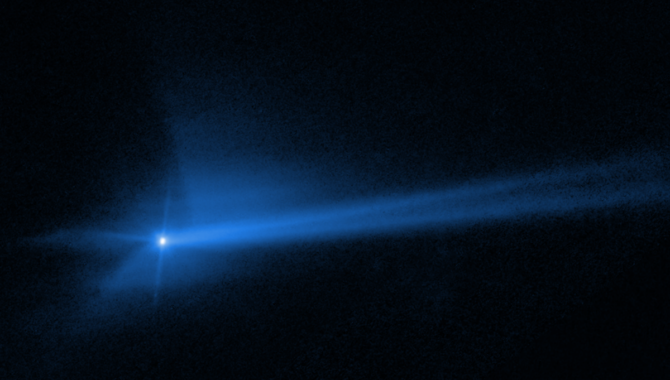

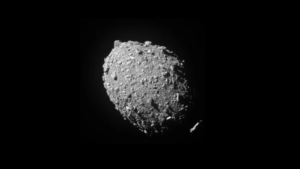

This image, captured by the Hubble Space Telescope, shows the aftermath of DART’s collision with the asteroid Dimorphos at 13,000 miles per hour, blasting more than 2 million pounds of dust and rock off the asteroid, and changing its orbit. Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, and Jian-Yang Li (PSI); Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

Representatives from NASA, FEMA, federal agencies and international partners discuss real challenges posed by hypothetical scenario.

In 1998, following a media frenzy over an erroneous report about a recently discovered asteroid, Congress tasked NASA with finding and tracking at least 90 percent of the Near-Earth Objects (NEO) larger than 1 km. In 2005, Congress enlarged the effort to include NEOs of 140 m or larger. Since then, NASA’s Center for NEO Studies (CNEOS) has identified 35,156 NEOs, 863 of which are 1 km or larger. The potential impact probabilities of these NEOs are infinitesimal.

In early April, a group of about 100 representatives from federal agencies and international partners gathered at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) for the fifth biennial Planetary Defense Interagency Tabletop Exercise (TTX5), to discuss the project management challenges they would face if an NEO were found that posed a significant threat.

Representatives from NASA, FEMA, and the planetary defense community participate in the 5th Planetary Defense Interagency Tabletop Exercise to inform and assess our ability as a nation to respond effectively to the threat of a potentially hazardous asteroid or comet. Credit: NASA/JHU-APL/Ed Whitman

In the exercise scenario, a hypothetical asteroid is discovered. Initial calculations indicate there is a 72 percent chance this hypothetical asteroid could impact Earth in about 14 years, and it could possibly be large enough to create a significant area of damage. In the exercise, there are large uncertainties about the size of the hypothetical asteroid and its future trajectory.

“That is actually the most likely scenario that we would face, if we’re successful in doing our search for the NEO [Near Earth Object] population, that we will know years, even decades in advance, of a potential impact threat and therefore have the necessary time to be able to prepare for it,” said Lindley Johnson, planetary defense officer emeritus at NASA Headquarters in Washington, speaking at a NASA media briefing. “A large asteroid impact is potentially the only natural disaster humanity has the technology to predict years in advance and take action to prevent.”

NASA and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) began sponsoring this series of tabletop exercises in 2013. Each exercise was built on a different hypothetical scenario and designed to emphasize unique elements of a planetary defense situation, from educating the public, to effective disaster management leadership, to building collaboration between federal, state, and local interagency partners for a coordinated response.

The asteroid Dimorphos was captured by NASA’s DART mission just two seconds before the spacecraft struck its surface on Sept. 26, 2022. Observations of the asteroid before and after impact suggest it is a loosely packed “rubble pile” object. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL

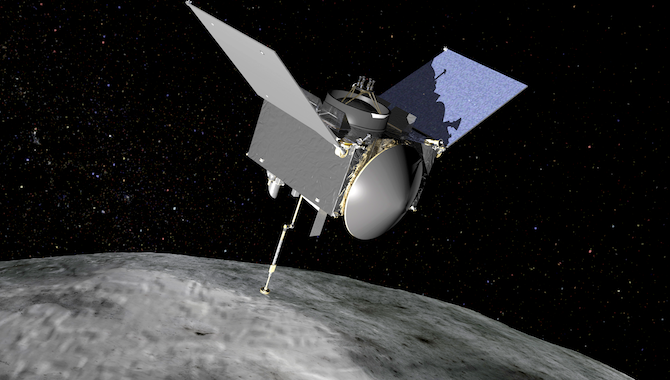

This is the first tabletop exercise since NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test successfully slammed a spacecraft into Dimorphos, a small asteroid orbiting a larger asteroid, Didymos. This impact on September 26, 2022, ejected more than two million pounds of the asteroid’s dusty surface rock into space and significantly altered the orbit of Dimorphos, proving the potential of a spacecraft to change an asteroid’s orbit.

“In TTX5, we added an international component to make sure that each level of exercise increased in difficulty, and they concentrated on different things, such as the amount of time it takes to warn for an accurate impact and what the different challenges are going to be occurring to each level of government,” said Leviticus “L.A.” Lewis, FEMA detailee to NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, speaking in the same media briefing.

“…As we work through these problems, we know it’s going to take an international effort and we concentrate on making sure that everybody’s familiar with the plans, familiar with each other, familiar with this type of extreme, but very rare scenario, so that we can work as a team when the time comes,” Lewis said.

The 14-year timeframe is the largest of any of the TTX scenarios. The TTX5 scenario is complicated by the fact that the hypothetical asteroid passes behind the Sun soon after it is discovered, delaying further observations from Earth for seven months.

“Now, there’s only a 72 percent chance that it could impact the Earth,” Johnson said of the hypothetical asteroid in the exercise. “It may actually slide past us and not be an impact at all. … And at this time, just after discovery, there are still uncertainties in the size of the object, ranging anywhere from 60 meters up to 800 meters.”

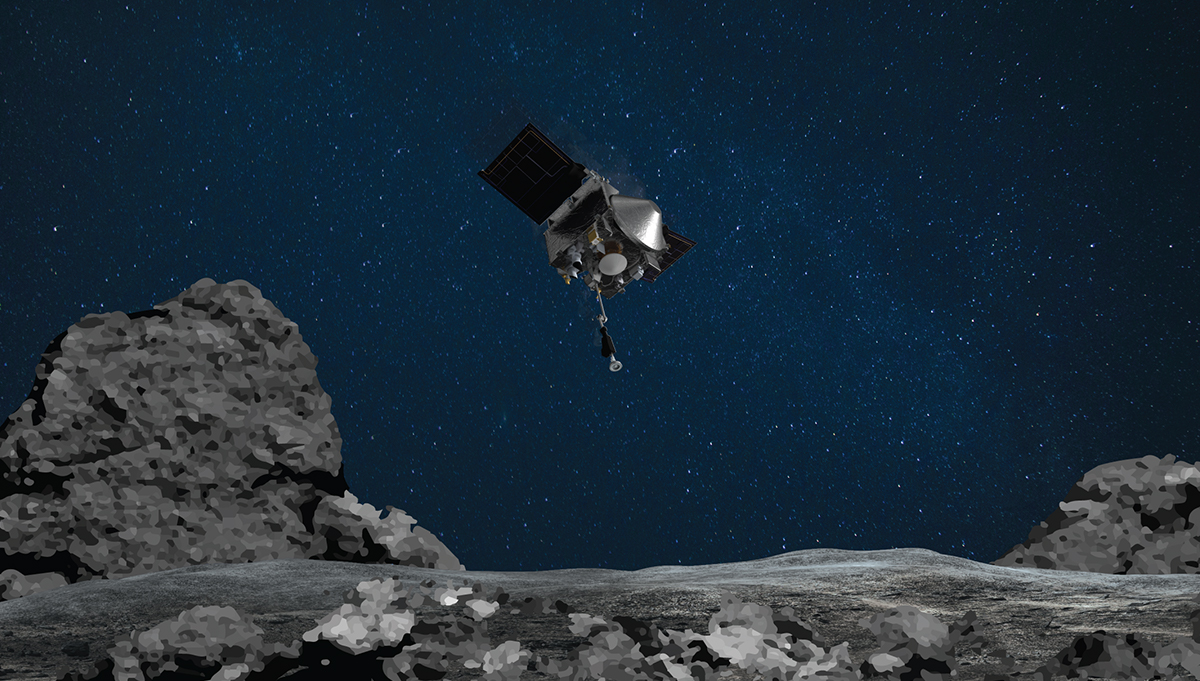

Participants discussed three possible courses of action. One was to wait six months to make further observations from Earth. Another was for the U.S. and NASA to lead a spacecraft flyby mission of the asteroid with the help of international partners. The third was to mount a purpose-built rendezvous mission to learn more about the target.

“So, starting development of a reconnaissance of the asteroid is one of the first things that you’d want to do when you know you have an impact threat, getting a spacecraft out to it as rapidly as possible to give us that more detailed information and reduce the uncertainty,” Johnson said. “Now, there are limitations in what a flyby mission can give you. A really detailed description of the asteroid could only be attained by spacecraft that actually rendezvous with it and observes it over a period of time.”

Participants found that the uncertainties in the scenario and the long timeline posed challenges in discerning the best path forward. Better information, they found, led to better decision making. They agreed they would want as much information as soon as possible to begin charting a course of action that could require the development of spacecraft and complex missions. They expressed concern about obtaining funding.

“Disaster preparedness was absolutely a component of this exercise, as was information sharing and public messaging.”

“We’re also looking at collaborative international space response. So, how would international partners come together to make space missions happen in response to this type of asteroid threat?” said Terik Daly, the planetary defense section supervisor at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. “Disaster preparedness was absolutely a component of this exercise, as was information sharing and public messaging. Because ultimately, this type of threat will have to bring together space, disaster preparedness, public messaging, and information sharing.

Participants identified 10 high-level gaps, such as unclear roles for some organizations in such a scenario and uncertainties about the decision-making process to pursue a space mission. They recommended developing the capability to rapidly launch an NEO reconnaissance mission, “repurposing existing spacecraft and/or instruments to rapidly gather information about an asteroid threat.” They also recommended additional demonstration missions such as DART to increase the maturity and reliability of the technology and explore other options, such as ion beams.

TTX5 was sponsored by NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, in partnership with FEMA and with the assistance of the U.S. Department of State Office of Space Affairs. To learn more about TTX5 and the participants’ recommendations, click here for the Quick-Look Report.