NASA astronaut F. Story Musgrave, STS-6 mission specialist, performs the first Extra Vehicular Activity of the Space Shuttle era in the payload bay of Challenger. Also on the EVA, but out of the frame here, was Donald Peterson. NASA astronaut Karol J. Bobko, pilot, took photographs through the aft flight deck windows. Credit: NASA

First flight of Challenger includes the first spacewalk of the shuttle program and an important test of a new generation of spacesuits.

On April 4, 1983, NASA launched the Space Shuttle Challenger on its first mission, STS-6, at the dawn of a new era in space exploration. It was the second operational flight of the program, following four test flights and STS-5, all flown with Columbia.

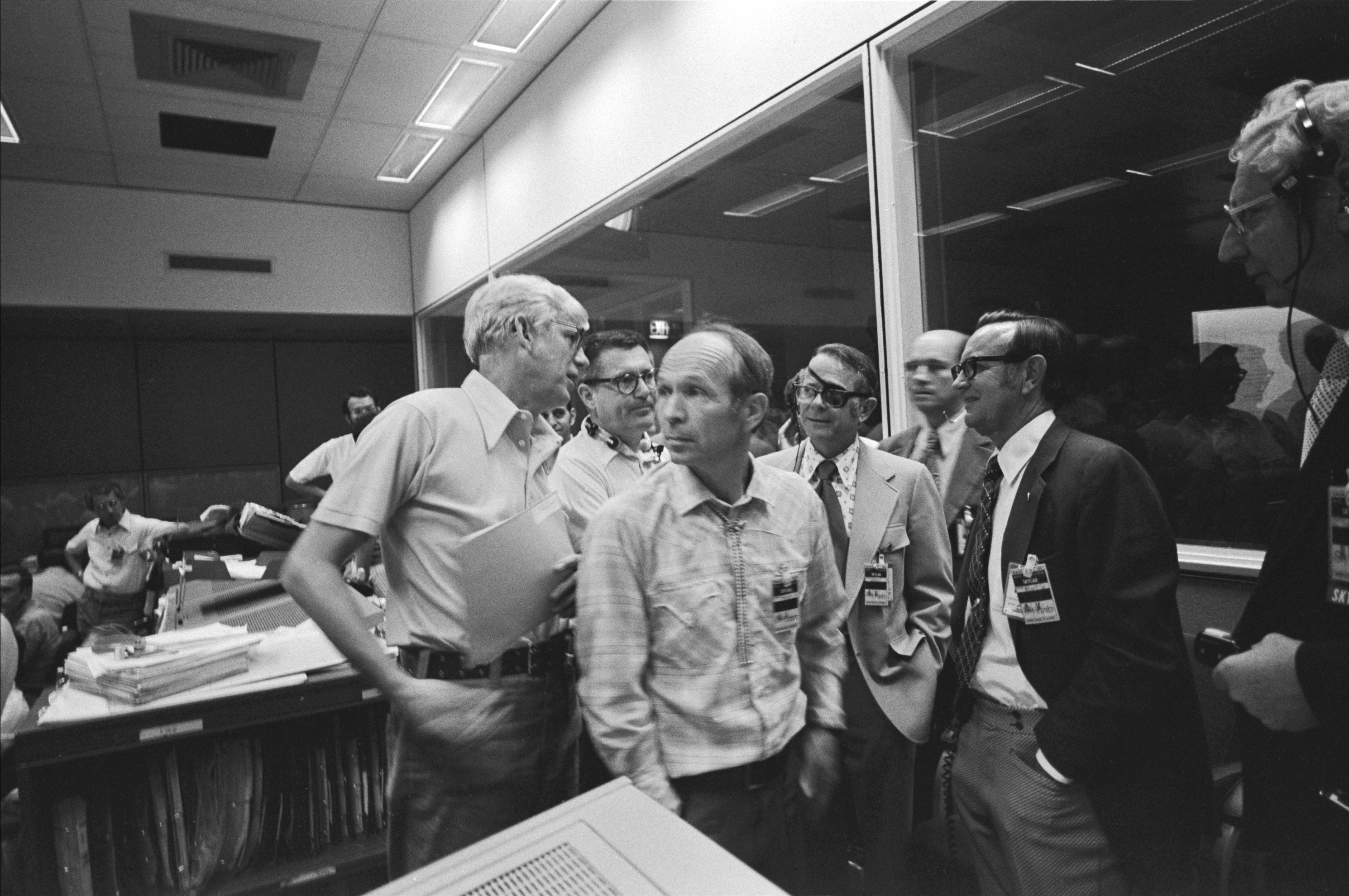

The first crew to fly the Space Shuttle Challenger pose with a model of the spacecraft. Seated are Commander Paul J. Weitz (left) and Pilot Karol J. Bobko. Standing are Mission Specialists Donald H. Peterson (left), and F. Story Musgrave. Credit: NASA

Commander Paul J. Weitz was the only member of the four-person crew who had been in space before, having spent 28 days making crucial repairs to the Skylab space station in 1973 with NASA astronauts Pete Conrad and Joseph P. Kerwin.

“The people I’ve compared notes with, we agree, it’s on the order of two to three weeks. I just can’t imagine spending much more than a month [in space],” Weitz recalled in an oral history. “Some time in the third week, I felt this desire to go home, but home was Earth. It wasn’t Houston, it wasn’t Texas, it wasn’t the U.S.; it was Earth. … But if you’re home for two or three weeks you’re ready to go again.”

So, after 10 years at home, Weitz was ready to go when the offer came to fly STS-6. And as a former test pilot, he was happy to see the long lists of program firsts that the mission contained. A list that grew even longer after a spacesuit malfunction forced the cancellation of a planned Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA) during STS-5.

“Each crew, each mission looks for some distinction you like to hang your hat on,” Weitz recalled. “Flying the inaugural flight, or the maiden flight, with Challenger, we thought it was a good deal.”

Pilot Karol Bobko and Mission Specialists Donald Peterson, and F. Story Musgrave were all making their first spaceflights after at least 16 years as astronauts.

One of the primary goals of the mission was deploying NASA’s Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS-1). It was the first in a series of satellites that would form a robust communications network in geosynchronous orbit, connecting spacecraft to other spacecraft, and to ground control stations on Earth.

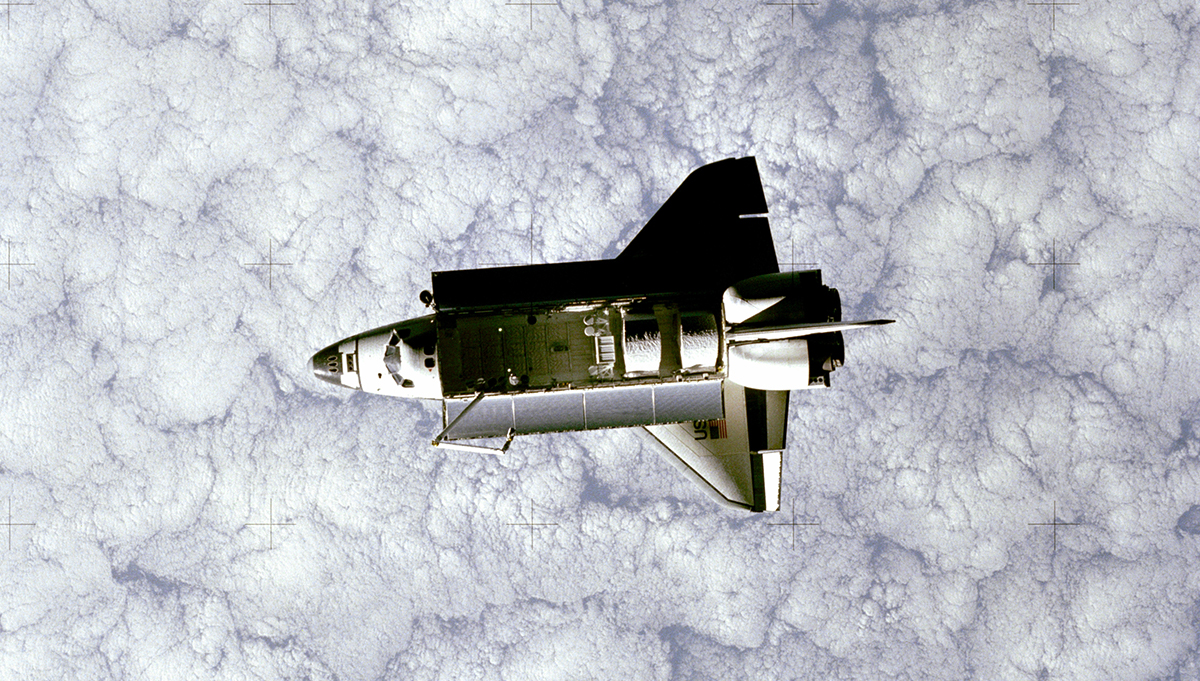

The crew deployed the first Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS-1) about ten hours after launch. The inertial upper stage (IUS) failed on its second burn and NASA painstakingly worked for weeks to raise the satellite to its functional orbit. Credit: NASA

The crew successfully deployed TDRS-1 from the payload bay. But the two-part booster system failed during the second burn, leaving the $100 million satellite drifting in a lower, unusable orbit. NASA engineers took advantage of extra propellant aboard the satellite, executing a series of 39 attitude control thruster burns over a period of weeks to eventually lift it into the correct orbit.

On April 7, 1983, Peterson and Musgrave prepared to move through the Challenger’s airlock into the payload bay for the first EVA of the Space Shuttle era, a crucial test of NASA’s new spacesuits.

“My responsibility was getting them into the suits, which is not a small responsibility,” Bobko recalled in an oral history. “I mean, you’re putting them into their own little … spacecraft. You know, it provides power and atmosphere and communications and meteoroid protection. It does everything. So, it’s kind of like launching a small satellite, except it’s got a man in it.”

During the spacewalk, Peterson was in the Space Shuttle Challenger’s payload bay, bracing himself with one hand while he cranked a ratchet wrench with the other, lowering a collar that had guided the TDRS-1 into space earlier in the mission. The task was a test, but it was arduous.

“My heart rate was very high,” Peterson recalled in an oral history. “Working in the suit is very hard. My legs floated out behind me. So, as I cranked, my legs were flailing back and forth, like a swimmer, to react to the load on the wrench. My heart rate was 192, okay, when I was cranking that wrench, so I was working very hard at the time.”

And then an alarm on his suit sounded. Musgrave stopped what he was doing and immediately went to help Peterson. And he was the perfect person for the job.

“The advantage we had was, Story was the Astronaut Office point of contact for the suit development, so Story knew everything about the suit there was to know. Story had spent, like, 400 hours in the suit in the water tank, so he didn’t really have to be trained. He probably knew as much as anybody on the training team about that,” Peterson recalled.

While the two checked the seals of Peterson’s suit, the alarm stopped, and they finished the EVA.

Astronaut F. Story Musgrave is assisted in a suit donning and doffing exercise in the weightlessness provided by a KC-135 zero-gravity aircraft. Credit: NASA

The first theory was that Peterson was working so hard that he was going through the oxygen in the suit too quickly and the flow of oxygen adjusted to a higher rate. But when an alarm sounded while NASA astronaut Shannon W. Lucid was training in her spacesuit on a treadmill, technicians narrowed in on a seal at the waist ring.

“There was a technician sitting there. These guys amaze me, but he looked at that, and he said, ‘You know, I’ve seen this same thing before. … I don’t remember where, but I’ll go find out,’ ” Peterson said. “And sure enough, he did, went back and went through a lot of film and said, ‘Looks just like this, doesn’t it?’ So, then they went in and changed the seals and all and fixed the problem.”

On April 9, 1983, STS-6 returned to Earth, landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Following a wet winter and spring, the dry lakebeds were too wet for the crew to land there and they were directed to the base’s massive runway.

“It was almost like a carrier approach, because there was water off the end of the runway, and then there was the runway,” Weitz recalled. “We had the first very fundamental primitive HUD, Heads-Up Display, as a landing aid. Other than that, it was just eyeballs out the window and do the best you can, which everybody did a good job, but we had a HUD.”

“But the landing went well. It was relatively smooth, and everything went just like it should as far as rollout was concerned. Five days, piece of cake compared to twenty-eight days,” Weitz said.

Visit APPEL KS’s Shuttle Era Resources Page to learn more about STS-6 and the other 134 shuttle missions over 30 years, missions that deployed key satellites, repaired the Hubble Space Telescope, enabled important new research, and were instrumental in construction of the International Space Station. The Shuttle Era Resources Page also contains important resources on the Challenger and Columbia accidents and enduring lessons learned.