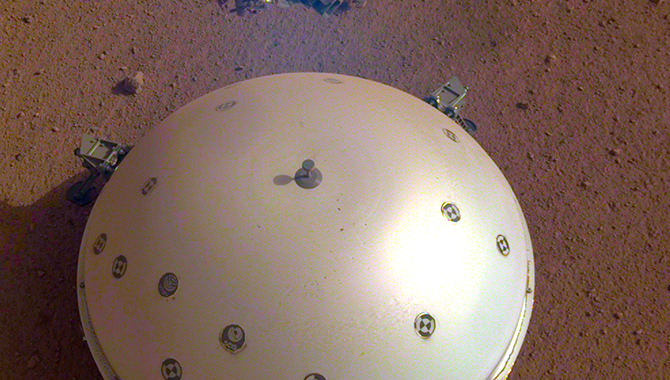

The twin 7 ft diameter solar panels that power NASA’s InSight Mars lander, shown here during final testing, are now a dull orange after years on the dusty surface of Mars. Energy production has dropped 90 percent.

Credit: NASA

Examination of data from the first seismometer on the surface of Mars just beginning.

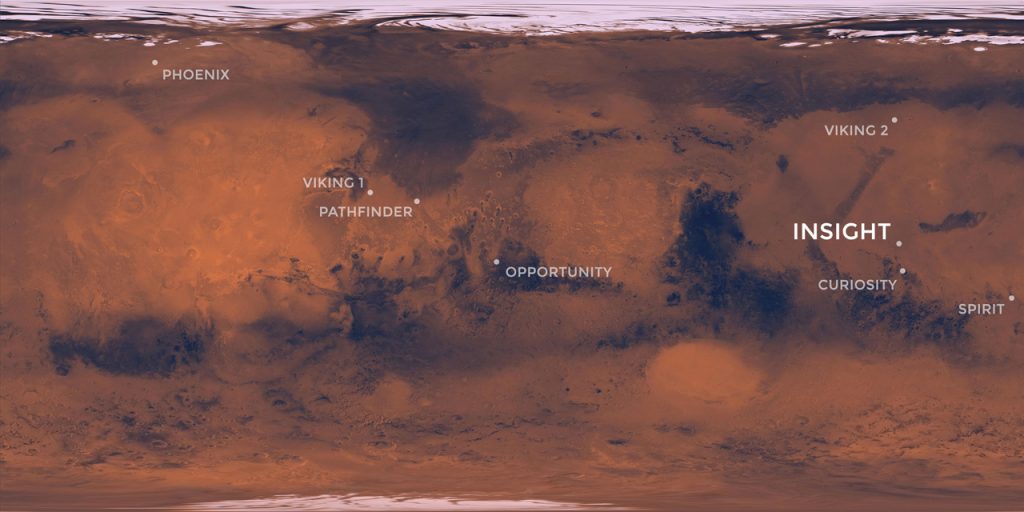

This summer, on the Elysium Planitia, near the equator of Mars, a NASA mission is winding down. The InSight Mars lander, powered by twin 7 ft diameter solar panels that were once gleaming black, but are now a dull orange, has seen energy production drop 90 percent. This isn’t the result of a single dust storm, but rather years on the dusty Martian surface. And as the hardware on Mars winds down, the work of examining InSight’s rich data is just beginning.

When InSight streaked into the thin atmosphere of Mars on November 26, 2018, little was known about the internal structure of the planet. How dense is the core? How large is it? How thick is the crust? What is its structure? Where is the seismic activity on Mars, and how frequent and powerful is it? These questions have implications beyond Mars, to all rocky planets that formed in the early solar system.

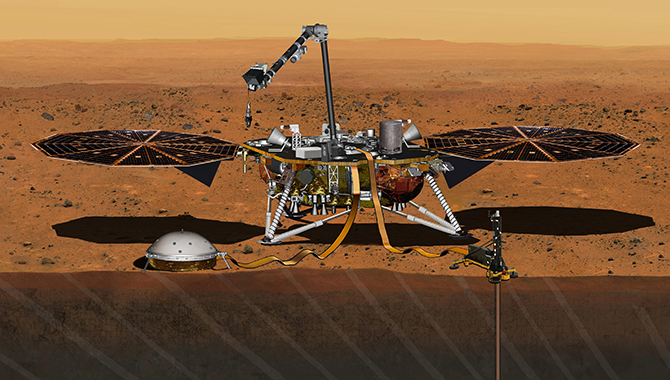

InSight landed at 11:52:59 a.m. PT (2:52:59 p.m. ET) on Nov. 26, 2018 near Mars’ equator on the western side of a flat, smooth plain called Elysium Planitia.

Credit: NASA

Tucked inside the spacecraft were the tools to help answer those questions, including the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument, a 65-pound, dome-shaped, high-sensitivity seismometer, the first to ever be deployed directly on the surface of Mars.

“I’ve been trying to get a seismometer on Mars for most of my professional career,” said InSight’s Principal Investigator, Bruce Banerdt, speaking at a recent NASA press conference. “This is a really super sensitive seismometer, which measures the motion of the ground, vibrations of the ground, at incredibly precise levels—down to the scale of a single atom’s radius. [That] is the size of the vibrations that we can sense with this.”

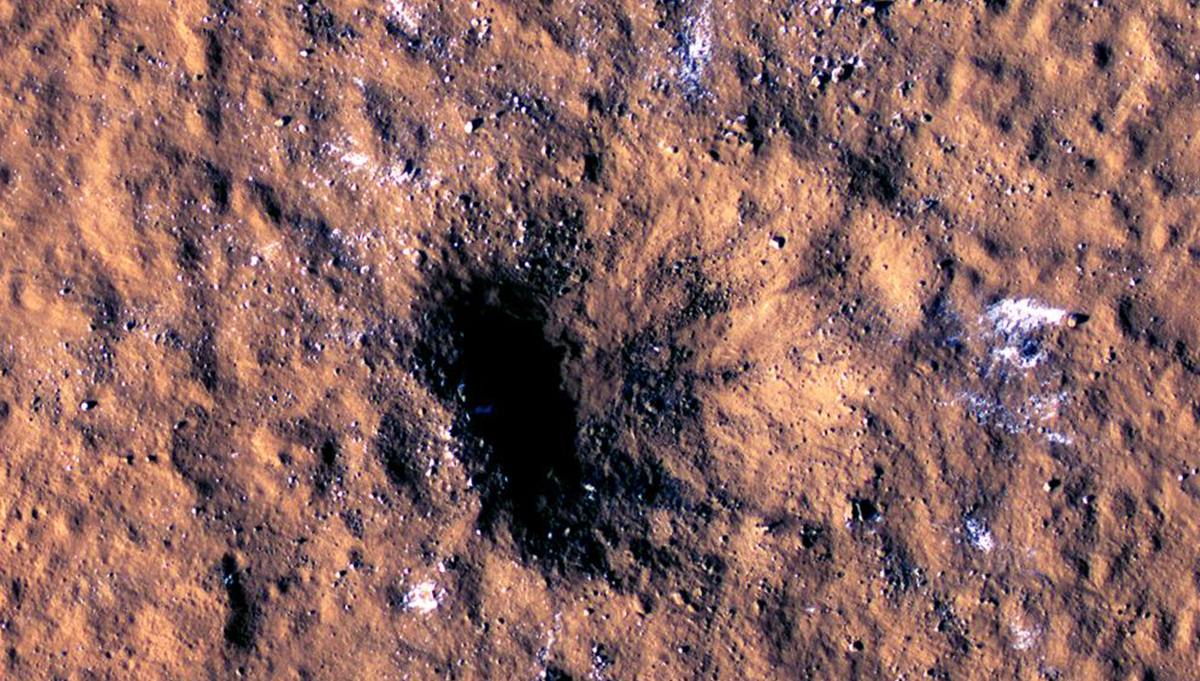

It was just 128 Martian days until InSight detected the first quake on Mars ever observed by humans. The April 6, 2019, quake was recorded as a deep rumbling followed by vibrations of the lander’s robotic arm. The event officially kicked off the field of Martian seismology, Banerdt said in a NASA press release at the time. In the years since, InSight has detected more than 1,300 quakes on Mars.

This artist’s rendering shows a cutaway of the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure instrument, or SEIS.

Credit: NASA

Banerdt explained that as the vibrations travel through the planet, created either by internal forces or by impacts on the planet’s surface, the waves are affected by the materials that they pass through. Seismologists employ techniques to decode how the waves are reflected or refracted to gain a better understanding about the interior of Mars.

“Basically, [the seismologists have] been able to map out the inside of Mars, for the very first time in history. “We are able to get the size of the core, we are able to deduce something about its density, and therefore the composition of the core. We’ve detected the bottom of the crust, and we are able to determine the thickness of the Martian crust,” Banerdt said, noting that the mission has met the goals that were set 10 years ago when it was proposed.

The data indicates the core of Mars is a molten mix of iron and lighter elements, much larger than expected at approximately 1,120 miles in radius. The planet’s crust is thinner than expected, between 15 and 25 miles thick, but with three internal layers. The top layer is about 6.2 miles thick.

The lander went into safe mode on January 7, 2022, as a large, regional dust storm grew to cover an area nearly twice the size of the continental United States. The storm was not nearly as large or intense as the storm that ended the mission of NASA’s Opportunity rover in 2018. As the dust settled, InSight exited safe mode on January 19. InSight’s solar panels, which once produced 5,000 watt-hours per Martian day when they were deployed, are now producing about 500 watt-hours.

“Even as our power is starting to dwindle, we are still doing great science at Mars,” Banerdt said at the press conference in May, noting the lander had just captured data from the strongest quake during its time on Mars. “It’s a magnitude 5 event. The biggest thing that we’ve seen before that was a magnitude 4, which is almost 10 times smaller. So even as we are starting to get close to the end of our mission, Mars is still giving us some really amazing things to see and to add to our data record. … This quake is really going to be a treasure trove of scientific information, when we get our teeth into it.”

The mission has also returned valuable data about the weather on Mars, and surprising findings about the planet’s magnetic field. Data from InSight will be studied for decades to come as scientists seek a better understanding of the interior of Mars and what that structure says about its formation from the swirling gas and dust of the solar system about 4.5 billion years ago. It will also provide information about the interiors of other rocky planets in our solar system, and the rocky exoplanets beyond it.

“…We’ve already been able to eliminate probably two thirds of the models for planetary formation that are out there just by looking at the size and the density of the core and the thickness of the crust,” Banerdt said. “And that’s just with the data that’s been published … in the last year or so. So, this is … a process that’s [just] beginning…”

“… These measurements and discoveries of InSight are going to hold for a very long time. They are unique and special, and we’ve made incredible advances in understanding the interior of Mars, that are not likely to be improved for decades,” said Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

Based on energy levels from early May, the team predicted that sometime this summer they will no longer be able to operate the SEIS continuously, instead operating it for several hours a day. Science operations will likely conclude by the end of summer, with all lander operations concluding by the end of 2022.

“Really, we are in an operating regime that we’ve never been in before. And so, as power goes down, we are not actually sure exactly how well the spacecraft will perform,” Banerdt said. “The other thing is that the weather is actually pretty unpredictable, this time of year. We could have a little bit more dustiness. We could actually have a dust storm that could shut things down a lot sooner than we expect. Or it may not be quite as dusty this year …, which allows to go longer.”

To learn more about the InSight lander and for status updates, visit the mission page.