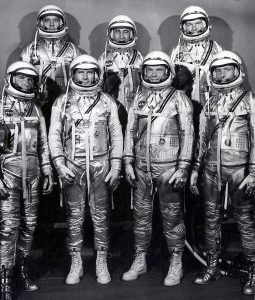

The original Mercury astronauts in June 1963 at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now Johnson Space Center, in Houston, Texas. From left-to-right: L. Gordon Cooper Jr., Walter M. Schirra Jr., Alan B. Shepard Jr., Virgil I. Grissom, John H. Glenn Jr., Donald K. (Deke) Slayton and M. Scott Carpenter.

Credit: NASA

Seven selected for Project Mercury went on to blaze bold paths in space exploration.

Sixty years ago this month, NASA introduced the first seven U.S. astronauts, a group selected from the nation’s top military pilots for Project Mercury. In the decade to come, the men would go on to leave their achievements writ large in the history of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs.

April 9, 1959 was a Thursday. The press conference that would immediately make celebrities of the accomplished pilots, began at 2 p.m. There was a short break very early in the process to allow reporters working for afternoon newspapers to make their early deadline.

“These men, the nation’s Project Mercury astronauts, are here after a long and perhaps unprecedented series of evaluations which told our medical consultants and scientists of their superb adaptability to their coming flight,” said Dr. Keith Glennan, NASA’s first administrator. “Which of these men will be the first to orbit the Earth, I cannot tell you. He won’t know himself until the day of the flight.”

It was, of course, John H. Glenn Jr., the only one of the seven drawn from the U.S. Marine Corps. M. Scott Carpenter, Walter M. Schirra Jr., and Alan B. Shepard Jr. were all U.S. Navy aviators. L. Gordon Cooper Jr., Virgil I. (Gus) Grissom, and Donald K. (Deke) Slayton were U.S. Air Force pilots.

The symmetry of their military backgrounds was unplanned, said Walter T. Bonney, NASA’s director of public affairs at the time. The men had been selected by their numbers not their names and backgrounds, Bonney assured the press.

The search criteria for the first astronauts was that they be less than 40 years old, shorter than 5 feet, 11 inches tall and in excellent physical health. They needed to be a graduate of test pilot school, be a jet pilot, and have at least 1,500 hours of flying time.

The group portrait of the original seven astronauts for the Mercury Project. Left to right at front: Walter M. Wally Schirra, Donald K. Deke Slayton, John H. Glenn, Jr., and Scott Carpenter. Left to right at rear: Alan B. Shepard, Virgil I. Gus Grissom, and L. Gordon Cooper, Jr.

Credit: NASA

All the astronauts were in their 30s, having been born in the 1920s, raised during the Great Depression, and having come of age as World War II drew to a close. In a sign of the times, three of the astronauts smoked during the press conference and were asked how they would quit during space flight. All were asked if their wives and families supported their new mission to explore the unknown.

They volunteered for Project Mercury for a variety of reasons. Slayton saw it as a natural extension of flight and “an excellent opportunity to be in on something new.” Originally scheduled to fly Mercury-Atlas 7, Slayton was found to have idiopathic atrial fibrillation. He went on to serve a crucial role as the senior manager of the astronaut office. He made it into space in 1973 as part of the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project.

Shepard said he saw Project Mercury as the starting point for space travel and was “delighted” by the opportunity to participate. He became the first American in space just two years later, on May 5, 1961. Like Slayton, he was grounded early in the space program because of health concerns and served important roles in management. He would later command Apollo 14, and become the fifth human to walk on the Moon.

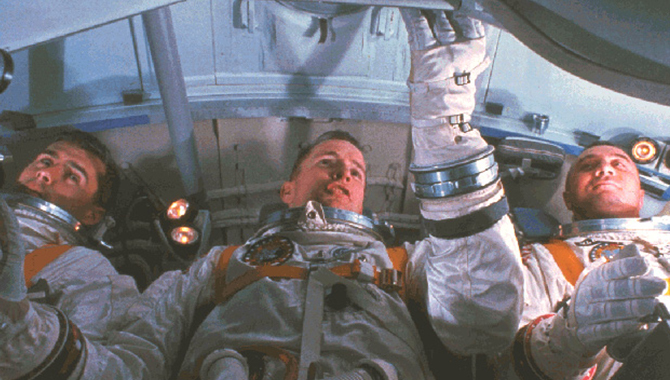

Schirra, too, saw the space program as a logical expansion of aviation and fitting with the national character of embracing new ideas. Schirra was the first astronaut to go into space three times. As the commander of Apollo 7, he bore a great deal of the responsibility for delivering a perfect mission as NASA worked to recover from the Apollo 1 fire.

Grissom told the gathered reporters that he had spent his career in service to his country and Project Mercury was another opportunity to serve “where they need my talents.” Grissom was the second American in space in Mercury-Redstone 4, and the command pilot of the first manned Gemini mission, Gemini 3. He was slated to be the commander of the first manned Apollo mission, as well, but died with his crew in a tragic fire during testing on the launchpad.

Cooper said he found the idea of space flight new and interesting. He flew the final Mercury mission Mercury-Atlas 9, which launched May 15, 1963. The mission included 22 orbits, which made him the first American to fly in space for more than a day. He retired in 1970.

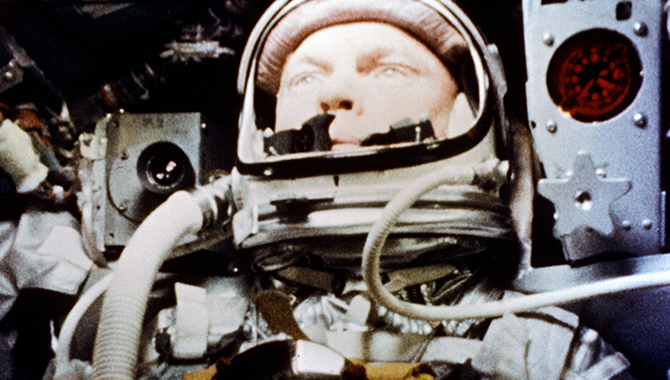

The launch of the MA-6, Friendship 7, on February 20, 1962. Boosted by the Mercury-Atlas vehicle, a modified Atlas Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), Friendship 7 was the first U.S. manned orbital flight and carried Astronaut John H. Glenn into orbit.

Credit: NASA

Glenn joked, “I got in on this project because it would probably be the nearest to Heaven I will ever get, and I wanted to make the most of it.” He quickly added that he saw the opportunity as a modern-day equivalent of the Wright Brothers. Glenn had already made the first supersonic transcontinental flight across the United States before becoming an astronaut. He became the first American to orbit the Earth. He was the first of the seven to retire and later the oldest human, 77, in space on Discovery mission STS-95.

“It is a chance to serve the country in a very noble cause,” Carpenter said. “It certainly is a chance to pioneer on a grand scale.” In 1962, Carpenter became the second American to orbit the Earth. His space career was cut short, however, when he suffered lasting effects after he broke his arm in an unrelated accident.

The astronauts and their families became overnight celebrities. LIFE magazine paid the group a shared $500,000 for their life stories and photographs. The astronauts were offered special $1 leases on new Chevrolet Corvettes. This intense public attention would stay with NASA deep into the Apollo program, bolstering it in many ways.

When asked about April 9, 1959, decades later, Shepard recalled, “Well, of course, that was one of the happiest days of my life. That was the day on which we all congregated officially as the U.S. first astronaut group. … I knew there was a lot of talent there, and I knew that it was going to be a tough fight to win the prize.”