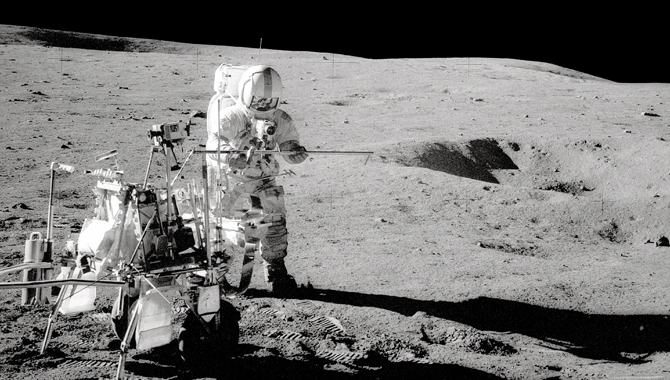

Alan B. Shepard, Jr., commander of Apollo 14, stands by the Modular Equipment Transporter cart that the astronauts used to carry tools, cameras and sample cases on the lunar surface.

Credit: NASA

Following Apollo 13, a Mercury Seven astronaut guides NASA’s next mission to the Moon.

On January 31, 1971, 49 years ago this month, Alan B. Shepard, Jr., Edgar D. Mitchell and Stuart A. Roosa blasted off from storied Launch Complex 39A at Kennedy Space Center, bound for the Moon. And although they didn’t dwell on it, each knew that they were carrying the future of the space program with them.

“We tried to downplay that,” recalled Mitchell, in an oral history. But it wasn’t just another mission. “Had we blown it, had it failed for whatever reason, that would probably have been the end of the Apollo Program right there.”

To avert any added pressure, the astronauts immersed themselves in their own considerable duties in the mission, Mitchell said. “We didn’t let it affect us for a minute. … When you’re carrying that personal load, you just don’t have room to carry a national load as well. I mean, you don’t allow yourself to do that. If you do, you’re foolish. You can’t carry that burden.”

Few were as connected to Apollo 13 as the crew of Apollo 14, however. Shepard, Mitchell and Roosa were originally scheduled to fly Apollo 13 and were bumped to give Shepard more training time in the simulators before his return to space flight following treatment for Ménière’s disease. And Mitchell provided valuable information to the Apollo 13 crew as they worked to return home.

July 1970: A fish-eye lens view showing astronauts Alan B. Shepard Jr. (foreground) and Edgar D. Mitchell in the Apollo lunar module mission simulator at the Kennedy Space Center during preflight training for the Apollo 14 lunar landing mission.

Credit: NASA

Mitchell recalls spending days in a lunar module simulator during the imperiled Apollo 13 mission, figuring out “…how to control, fly manually the lunar module with the command module on its nose, because we’d never done that before. It wasn’t obvious that we knew how to do it,” Mitchell said. “There was no choice. If they were going to come home, we had to have some answers, and we didn’t have answers then, if they’d ever had to use that manual procedure — which they did on the very last burn, coming back.”

Shepard was one of the Mercury Seven and had excelled during tough competition among the astronauts to become the first American in space. He had been slated to command Gemini 3, the first crewed mission of that program, before being diagnosed with Ménière’s disease and losing his flight status. Now, six years later, following a new surgical procedure in 1969, he was the commander of Apollo 14.

The astronauts had to overcome several technical challenges to land on the Moon. The first was early in the mission, about 3 hours and 41 minutes after liftoff, when the crew was unable to make an initial docking maneuver with the lunar module because capture latches didn’t deploy properly. After several attempts failed over two hours, the crew bypassed the initial maneuver and went directly to a “hard dock.”

This accomplished the task, but because this docking maneuver is performed again in lunar orbit and is crucial to returning all of the crew safely to Earth, NASA performed an extensive televised inspection of the docking system before determining it was safe to proceed to the Moon.

At the Moon, a short was discovered in the LM’s abort switch when it began engaging without input from the crew.

“The significance of that problem was that if we had started down to the lunar surface … and that malfunction occurred, presumably it would trigger a whole series of events that started us back toward the command module,” Mitchell recalled, adding that the descent engine would have automatically shut off, the LM would have separated from the descent stage, and the ascent engine would have ignited. “So, if we wanted to land on the lunar surface, there was no way we could allow that problem to persist.”

Unable to physically repair the switch in the time available, NASA’s computer experts developed a workaround so the computer could ignore the switch’s signal when it tripped again. Shepard took on many of Mitchell’s duties at this point in the mission so that Mitchell could manually enter keystrokes for the workaround, finishing with just seconds to spare.

Unfortunately, in the process, the computer had lost communication with the LM’s landing radar. “So we had a rule that said if the landing radar was not updating the computer by the time you were down at a level of about 13,000 ft, then you have to abort; you have to get out of there,” recalled Shepard, in an oral history.

Mission control quickly determined that the landing radar was working but was locked on infinity. “So, we pulled the circuit breaker, put it back in, and sure enough the landing radar came on. And shortly after that we got cleared to land with a margin of 1,000 ft or so, which was a close thing. … We came on down, made a very, very soft landing,” Shepard said.

“We shut off the switches and Ed Mitchell turned to me and said, ‘Alan, what were you going to do if the landing radar had not been working by 13,000 feet?’ I looked at him and I said, ‘Ed, you’ll never know.’” Shepard recalled. Because of his extensive training in a lunar landing simulator, however, he felt confident that he could have landed without radar. “I would have gone down. I’d come that far.”

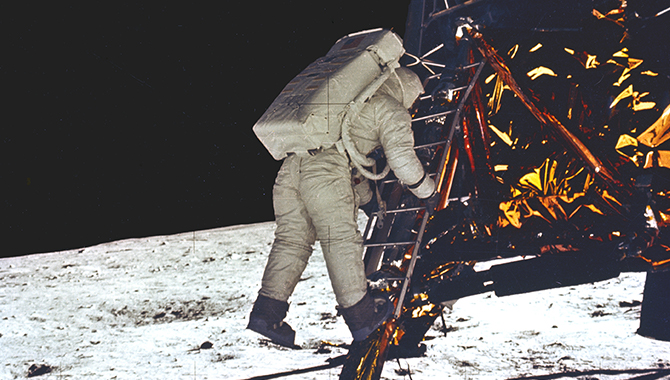

And so, the first American in space, who had been restored to full flight status just on May 7, 1969, became the only Mercury Seven astronaut to walk on the Moon. “There was that sense of self-satisfaction immediately. But then that went away, because we had a lot of work to do. But I’ll never forget that moment,” he said.

This photograph was taken by one of the Apollo 14 astronauts at the close of their first extravehicular activity (EVA). The crescent Earth can be seen in the far distant background.

Credit: NASA

Another memorable moment came when he and Mitchell stood on the lunar surface, looked up into the black sky and saw Earth. “Now planet Earth is only four times as large as the Moon, so you can really still put your thumb and your forefinger around it at that distance. So, it makes it look beautiful; it makes it look lonely; it makes it look fragile. You think to yourself, just imagine that millions of people are living on that planet and don’t realize how fragile it is. I think this is a feeling everyone has had and expressed it in one fashion or another. That was an overwhelming feeling in seeing the beauty of the planet on the one hand but the fragility of it on the other,” Shepard recalled.

Apollo 14 left the lunar surface on February 6, 1971, carrying about 95 pounds of samples, including one rock, portions of which might have been on a return trip to Earth. They left behind several science experiments, two golf balls hit by Shepard and a metal rod Mitchell tossed as a javelin.

Apollo 14 splashed down in the South Pacific Ocean on February 9 and was recovered by the USS New Orleans. The mission was a success, to be followed seamlessly by three more successful Apollo missions.