Charles W. Mathews, Manager, Project Gemini (right) stands and the flight director's console, viewing Gemini X flight display data in the Mission Control Center on July 18, 1966. With him, from left, are William C. Schneider, Mission Director; Glynn Lunney, Prime Flight Director; and Christopher C. Kraft Jr., MSC Director of Flight Operations.

Credit: NASA

Program manager guides team to success of Gemini III.

In February 1963, Charles W. Mathews was called to the office of James C. Elms, the recently appointed Deputy Director of NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC). It was a chaotic time for the MSC, which was launching the first NASA astronauts into space with Project Mercury, moving to new facilities in Houston, Texas, and working on both Project Gemini and Apollo. Mathews recalled Elms questioning him about the challenges of Apollo and landing on the Moon.

“I couldn’t imagine why he was really asking me these questions. And, it turned out it had nothing to do with what he was really wanting to know. What he was really wanting to know was: Was I qualified to become the Gemini Program Manager?” Mathews recalled, in an oral history.

Project Gemini had fallen behind its optimistic schedule, slowed as engineers worked through development challenges centered on the spacecraft and its crucial rendezvous equipment, fuel cells, and ablative thrusters. These advanced systems were at the cutting edge in 1963. Although much of the equipment for rendezvous had precedents in military aeronautics, the fuel cells and ablative thrusters were fresh technologies.

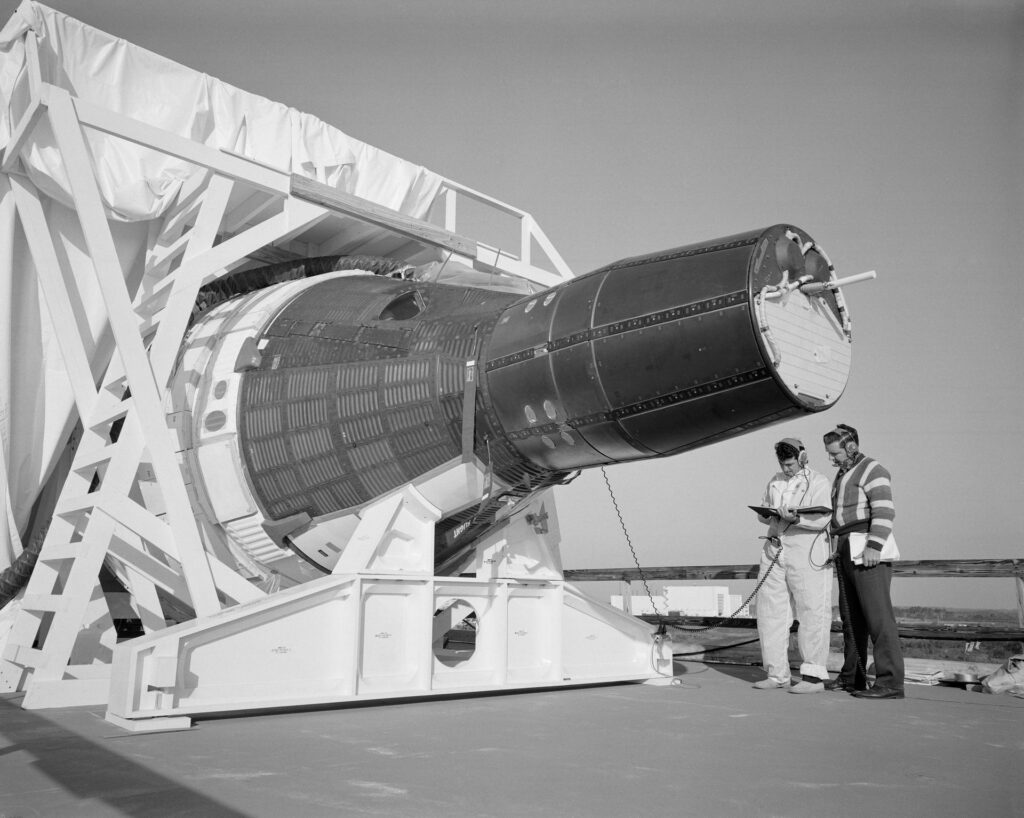

Gemini-3 spacecraft (final configuation) during test at Boresight Range, Merritt Island launch area in 1965.

Credit: NASA

“…No one had any experience with them,” Mathews recalled of the fuel cells. “It was a brand-new development. The process by which they operated had been demonstrated and validated, but that isn’t saying that you know really how to build a working fuel cell that will last a reasonable length of time. So that was kind of expected to be a dominant problem in the program, I think, from the word ‘go.’ ”

More was known about ablative technology when applied to heat shields and the rocket nozzles of large engines operating in a steady state. But Gemini’s maneuvering thrusters were much smaller than previous applications, and they needed to operate in rapid pulses during precision rendezvous maneuvers.

Astronauts Virgil I. Grissom (center) and John W. Young (left), prime crew for the Gemini-Titan 3 mission, are shown inspecting the inside of Gemini spacecraft at the Mission Control Center at Cape Kennedy, Florida in 1964. Riley D. McCafferty is at right.

Credit: NASA

“So, it was with great surprise that these things would burn through very rapidly. …Here was a program dedicated to conducting rendezvous that couldn’t provide maneuvering thrusters that would work. And so, again, just like the fuel cell, it was kind of back to a research program for a while, as compared to a development program,” Mathews said.

“The fuel cells’ problems were the type of things like material problems, contamination problems, water scavenging problems, the kind of things that would be very natural. With the ablative thrusters, we tried to nickel and dime it at first, but then decided we had to do something rather fundamental, and we ultimately got them to work,” Mathews said.

Mathews’ approach to Project Gemini—once he found it on the fourth floor of a nondescript General Services Administration building in the middle of Houston—was to develop a schedule that allowed engineers the time they needed to advance the key technologies, with a rapid launch schedule thereafter, based on his faith in the main contractors. Then, Mathews traveled the country meeting with Gemini subcontractors.

By going out and working directly with these subcontractors, Mathews recalled, he not only learned the nature of the challenges they were working to solve but was also able to speak with them about the great importance of the work they were doing to advance space exploration.

“So, the spacecraft moved along in an undesirably slow way, I would say, but the problems were solved one by one, and as they were solved, we also injected really new management techniques…,” Mathews explained. “…We organized an extremely rigorous change control system, where no change could be made—this applied to the launch vehicle as well as the spacecraft—no change could be made until it was not only reviewed by the contractors, but was brought up to the program office and could only happen if I personally signed [off] for it.”

The first crewed Gemini flight, Gemini III, lifted off Launch Pad 19 at 9:24 a.m. EST on March 23, 1965.

Credit: NASA

On March 23, 1965, 58 years ago this month, Gemini III launched from Cape Kennedy Launch Complex 19 aboard a Titan II rocket. It was the third launch of the program, and the first with astronauts aboard. Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom was the Command Pilot and John W. Young was the pilot. The spacecraft, nicknamed the “Molly Brown,” was in space for nearly five hours, splashing down in the Atlantic Ocean.

“So, we’re into the flight program. …The spacecraft worked with really no outstanding problem, so we were really ready to go. Nobody had gotten too excited yet, in terms of the public or anyone else. But it was very satisfactory,” Mathews recalled.

Gemini included 10 crewed missions, providing NASA with a wealth of information about rendezvous in space and extravehicular activities. Gemini astronauts went on to form the backbone of Apollo, with eight walking on the Moon. In November 1966, Project Gemini flew its last mission and NASA turned its full attention to Apollo.

“As the program phased down, we started transferring these people, and just as we had judged, it served a very useful purpose. Some very key activities in Apollo ultimately could be credited to some of the Gemini experience,” Mathews said. “The majority of the astronauts in the Apollo Program were Gemini-trained, but the training of the flight controllers was [also very] important, because this had become a very sophisticated operation…”

Mathews went on to serve as Director of the Apollo Applications Program and later Deputy Associate Administrator in the Office of Manned Space Flight, before retiring in 1976 as the Associate Administrator for the Office of Applications.