In June of 1969, Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin prepare to practice spacewalk techniques, walking over a simulated lunar surface in a facility at what is now NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

Photo Credit: NASA

In June 1969, NASA charges Apollo 11 with a single, straightforward objective — Perform a manned lunar landing and return.

In December of 1968, as the crew of Apollo 8 was flying to the Moon, orbiting it 20 times, and returning to Earth, Donald K. “Deke” Slayton, NASA’s Director of Flight Crew Operations, had a series of meetings with Neil A. Armstrong. Would Armstrong take the lead for the “third one down,” Slayton asked, and what was his input about who was right for the crew?

“I think at that point in time I did not really expect that we’d get the chance to try a lunar landing on that flight,” Armstrong recalled in an oral history. “…The lunar module had not flown, hadn’t even been in Earth orbit. We didn’t know if we could communicate with two vehicles simultaneously at lunar distance. We didn’t know whether the radar ranging would work. A lot of things we just didn’t know at that point.”

What Armstrong did know was that any Apollo mission was a spectacular opportunity, no matter what the flight objective. He happily accepted the offer. Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin was selected as the Lunar Module Pilot, and Michael Collins was selected as the Command Module Pilot.

The Lunar Module, seen here from the Command Module, is tested in Earth orbit during Apollo 9 in early 1969. Apollo 10 tested the system in lunar orbit later that year. Photo Credit: NASA

In the spring of 1969, the pieces fell into place dramatically. In March, the lunar module which had fallen behind schedule as engineers struggled to remove weight while maintaining durability, performed flawlessly in Earth orbit during Apollo 9. In May, the crew of Apollo 10 demonstrated that the system worked well in lunar orbit. The Apollo Program was overcoming technical challenges at a staggering pace.

On June 11, Sam C. Phillips, a Lieutenant General in the U.S. Air Force who was on detail serving as the Apollo Program Director, announced that NASA would attempt the first human lunar landing during the next Apollo mission. It would launch on July 16. The “third one down” had become the one.

Phillips was a skilled program manager who built a reputation working on the sprawling Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile system, driving advancements in electronic circuitry that would filter down into consumer products for decades to come. He took a systems engineering approach to Apollo, fostering productive contractor relations built on frank communication and trust.

On June 26, Phillips and George E. Mueller, NASA’s Associate Administrator for Manned Flight, released a document designating a single, straightforward objective for Apollo 11: Perform a manned lunar landing and return.

NASA leaders decided that Apollo 11 wouldn’t attempt any science experiments that couldn’t be successfully deployed in ten minutes in case the astronauts were forced to abruptly leave the lunar surface. The Early Apollo Surface Experiment Package (EASEP) contained just two experiments that met that criterion, a seismometer to record meteorite impacts and moonquakes, and an array of fused silica cubes that could reflect a laser beam back to Earth with such precision that scientists could measure the distance to within eight centimeters.

Apollo 11 Commander Neil Armstrong flies the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle in one of 20 lunar landing simulations he performed. Photo Credit: NASA

In June, Armstrong logged 8 more flights in the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV), bringing his total number of simulated lunar landings to 20. The LLTV had just been cleared for a return to flight on June 6, following an investigation into a crash on December 8, 1968. Armstrong had narrowly escaped a crash himself in May 1968, ejecting from the LLTV’s predecessor, the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle, about three and a half seconds before it hit the ground and burst into flames.

“We lost three of those vehicles,” Armstrong recalled. “It was a contrary machine and a risky machine, but a very useful one.”

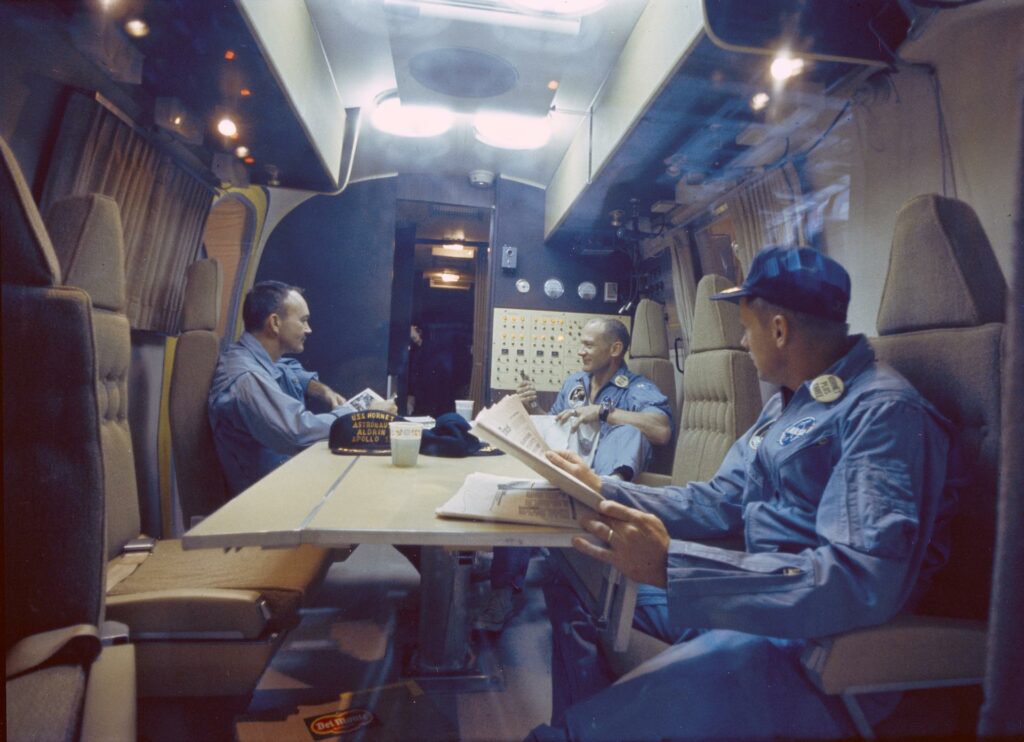

On June 5, the USS Hornet, the aircraft carrier that had pulled the uncrewed Command Module of the Apollo 202 test flight out of the Pacific Ocean in 1966, was selected by NASA and the U.S. Navy as the prime recovery ship for Apollo 11. When the mission was designated as the first lunar landing attempt the next week, that meant the ship’s crew became part of NASA’s efforts to contain any possible contamination from the Moon and that NASA’s Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF) would be aboard the ship.

NASA devised a system to lower containment garments to the astronauts from a helicopter. The astronauts would then put the garments on after climbing from the capsule to a waiting raft. The crew of the Hornet would lift each astronaut via helicopter onto the ship, where they would go immediately into the MQF. The plans were finalized and approved on June 26.

Armstrong and Aldrin practiced spacewalk techniques multiple times during June, walking over a simulated lunar surface in a facility at what is now NASA’s Johnson Space Center. They practiced deploying the EASEP experiments as the instruments’ principal scientists looked on and provided feedback.

In between training in June, the Apollo 11 astronauts pored over manuals for the spacecraft and reviewed “what if” scenarios.

With the June 6 announcement that Apollo 11 would be the first attempt at a human lunar landing, the crew of the USS Hornet was trained on NASA’s contamination containment process, which included the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF), which was placed on the ship. In this photo, from left, Michael Collins, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Neil Armstrong relax following the mission. Photo Credit: NASA

“We’d talk about strategies or “What are we going to do if this happens?” Or, “Are you sure you know how to handle this?” That’s where we spent our time. You know, normally… a lot of unexpected things happen, and usually they’re not the ones you practice. But the fact that you practiced a lot of different things puts you in the proper mindset to handle whatever it is that comes along, even if it isn’t the one that you’ve experienced before. And I think that happened on a lot of the flights,” Armstrong recalled.

Finally, in June, the crew, led by Collins, worked to select names for the Command and Lunar modules. Some NASA officials thought the names used in earlier missions—gumdrop, spider, Peanuts, and Snoopy—had been frivolous and asked the crew to select names that matched the gravitas of the upcoming mission. The crew ultimately landed on Columbia and Eagle.

To learn more about the Apollo Program and the technical challenges engineers overcame to land the first humans on the Moon, visit the Apollo Era Resources page of the APPEL KS Knowledge Inventory.