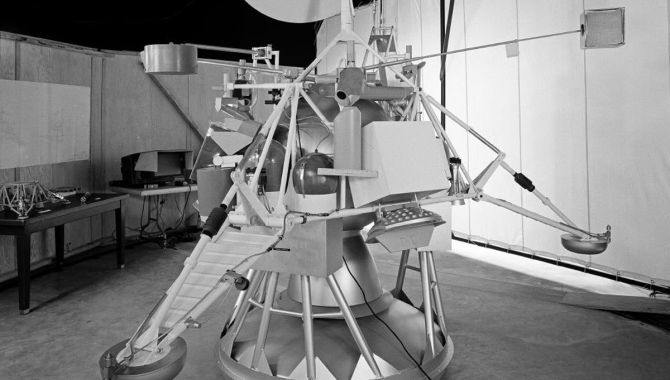

Surveyor 1 was a three-legged spacecraft, 10 feet tall, with large pads at the end of each leg. At about 650 pounds, it was a true test of the lunar surface and the first controlled-descent, soft landing on the Moon.

Credit: NASA

Robotic lander series demonstrated lunar surface would support Apollo’s Lunar Module.

Monday, May 30, 1966, was sunny at Cape Canaveral, Florida. It had been less than three months since Neil A. Armstrong and David R. Scott narrowly averted disaster during Gemini VIII. Gemini IX-A would launch in just four days. At Launch Complex 36, an Atlas-Centaur rocket towered over the landscape.

Even as NASA was developing the rendezvous and docking skills with Gemini that would be crucial for the success of a Moon landing, science was still struggling to characterize the lunar surface. Both the U.S. and the Soviet Union had landed probes on the Moon by this point, but they were light weight and questions remained about the characteristics of the lunar surface.

Scientific hypotheses about the surface of the Moon as late as 1958 “… included deep fields of dust into which a spacecraft might sink; a labyrinth of ‘fairy castles’ such as children build by dripping wet sand at the beach; electrostatic dust that might spring up and engulf an alien object; and treacherously covered crevasses into which an unwary astronaut might fall,” wrote Edgar M. Cortright, then Director of NASA’s Langley Research Center, in Apollo Expeditions to the Moon.

Aboard the Atlas-Centaur rocket that morning in 1966 was Surveyor 1, the first in a series of robotic lunar landers designed to better quantify the lunar surface. Surveyor 1 was a three-legged spacecraft, 10 feet tall, with an aluminum frame and large pads at the end of each leg. At about 650 pounds, it would be a true test of the lunar surface and the first controlled-descent, soft landing on the Moon.

The spacecraft was equipped with a television camera, capped by a mirror assembly that rotated 360 degrees, going about 225 degrees in one direction and about 135 degrees in the other. NASA could also tilt the oblong mirror within the assembly. The camera was equipped with both wide angle and narrow angle lenses for even greater flexibility.

Before launch, the Surveyor 1 team, which was based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, took a model of the spacecraft into the desert and camped there, practicing for weeks how to take panoramic images with the camera, assembling the series of still images the system produced into a single, larger image.

“We would create two teams. We’d have a stopwatch. We’d say, ‘Okay.’ There would be a whole bunch of little stacks of images. They would be passed out to the team and the team would automatically put them down. We got really efficient, that within about five minutes after any kind of landing we had a panorama for the scientists to take a look at,” recalled Justin J. “Jay” Rennilson, in an oral history. Rennilson was a co-principal investigator on the Surveyor television experiment.

“Now understand, we had done a lot of engineering, failure modes, a whole bunch of things like that, and when we got done, the people that were directly involved … we said, ‘Well, the probability is maybe 10 to 15 percent success,’ ” Rennilson recalled. “When Surveyor 1 was about ready to go, they said, ‘Well, okay, there’s only a 10 or 15 percent success. But in case it lands we’re prepared.’ ”

Surveyor 1’s descent was powered by a large solid-propellant retrorocket and a bank of three thrusters. A Doppler radar system measured descent velocity, feeding data into the spacecraft’s computer, which then controlled the spacecraft as it slowed from 6,000 miles per hour to less than 5 miles per hour at touchdown. The landing, on June 2, 1966, was televised.

“There was still sufficient doubt as to how much support the surface was going to be,” Rennilson said. The lunar surface had supported the Soviet Union’s Luna 9 capsule, which had made the first survivable lunar landing in February—impacting the surface at about 14 miles per hour and bouncing. But Luna 9 weighed about 215 pounds. Surveyor was significantly heavier and attempting the first controlled soft landing.

During the live broadcast, CBS journalist George Herman explained that the first images Surveyor 1 would send back to Earth would be of the spacecraft’s foot pads on the lunar surface. The key question: “…Will the foot pad be buried deep in dust?” he said.

“Alone on a desolate plain of the Moon’s Sea of Storms (Oceanus Procellarum), Surveyor I stands quietly, its job well done,” wrote Homer E. Newell, then Associate Administrator, NASA, in describing this photograph.

Credit: NASA

As the team, excited with Surveyor 1’s successful landing, began sharing those early images during the broadcast, they revealed a small ridge of loose dust surrounding the foot pad, but the pad was clearly resting on a firm ground. It had not sunk significantly into the lunar surface. Over the next six weeks, Surveyor 1 returned more than 11,000 images, many assembled into wide panoramas that provided unprecedented detail of the lunar surface for the time.

In the next 19 months, NASA launched six more Surveyors. Surveyors 2 and 4 experienced malfunctions and crashed on the Moon. Surveyor 3 was the first mission equipped with a motorized, extendable arm and scoop to dig samples from the lunar surface and pile them so they could be photographed and examined. Surveyor 5 landed at Mare Tranquillitatis, returning panoramic images of the landing site of Apollo 11.

“What proved to be the most accurate prediction,” Cortright wrote, “… likened the Moon to a World War I battlefield, bombarded by a rain of meteoroids throughout the millennia, and churned into a wasteland of craters and debris. The absence of an atmosphere and the low gravitational field would allow small secondary particles to be blasted from the surface by a primary meteoroid impact and thrown unimpeded halfway around the Moon. This led to the concept of a uniform blanket of ejecta over the entire Moon.”

With five controlled-descent, soft landings on the Moon, the Surveyor program set the stage for the Apollo Moon landings that followed. To learn more about the race to the Moon and NASA’s Moon landings, visit the APPEL Knowledge Services Apollo Era Resources page.